- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

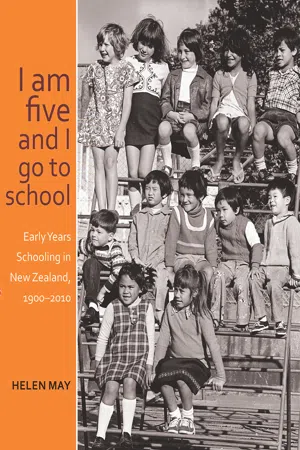

The twentieth century was a time of great change in early years education. As the century opened, the use of Froebel's kindergarten methods infiltrated more infant classrooms. The emergence of psychology as a discipline, and especially its work on child development, was beginning to influence thinking about how infants learn through play. While there were many teachers who maintained Victorian approaches in their classrooms, some others experimented, were widely read and a few even travelled to the US and Europe and brought new ideas home. As well, there was increasing political support for new approaches to the "new education" ideas at the turn of the century. All was not plain sailing, however, and this book charts both the progress made and the obstacles overcome in the course of the century, as the nation battled its way through world wars and depressions. It's an interesting story as the author discusses changes in school buildings, teaching practice and teacher education, the teaching of reading and other curriculum areas, Maori education and the emergence of kohanga reo and the teaching of Maori language in primary schools. Along the way we meet a range of individuals, including C.E. Beeby, Sylvia Ashton-Warner, Gwen Somerset, Don Holdaway, Elwyn Richardson, Marie Bell and Marie Clay and the many less well-known but significant people who worked in or influenced early years education. We also meet many well-known New Zealanders who have recounted their first days at school. This is a fascinating account of a rich history that has involved us all. And yes, school milk gets a mention.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I am five and I go to school by Helen May in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Youngest Children at School

On 7 March 1980, Campbell Gilbert walked to school with his mother, younger sister and the family dog. It was his first day at Arthur Street School in Dunedin. In the morning he was given a new unlined exercise book and on the first page he traced over a story printed by his teacher, Miss Nola Wyber, which read, ‘I am five and I go to school’.1

Campbell Gilbert

Miss Wyber, who retired in 1988, kept Campbell’s book of stories along with other memorabilia, records and resources from her long teaching career. Kindly lent to the author, these have been a useful resource. Miss Wyber remembered Campbell as ‘a lovely wee boy.’ His neat book is full of charming pictures. On his first day he drew a picture of his dog, three balloons, and a birthday cake – with four candles!

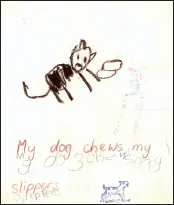

Like most New Zealand children, Campbell started school on his fifth birthday and this was celebrated with a party. His next story has a drawing of himself and his teacher has written ‘I live in Michie St’ (actually it was Lawson Street). Campbell clearly has his own story in mind in a picture of a brown dog and ‘My dog chews my slippers.’ He is rewarded with a stamp of a dog for this story, as he has copied the teacher’s printing. This is fast progress.

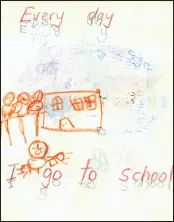

A few days later, Campbell again prints underneath Miss Wyber’s printing to say, ‘Every day I go to school.’ He draws a picture of himself, three children and the school. We do not know the extent to which Campbell determined the content of his first stories, nor do we know whether this story reflects his pleasure in going to school ‘every day’ or concern that he has to go ‘every day’! The smiling child suggests that he is happy to be going to school.

Campbell’s story on his first day at school appealed to me as a title for this book. Miss Wyber could recall her past pupils and in 2010 traced Campbell, who was working as an investment banker in London. His first book was returned to the safe-keeping of his family.

‘I am five and I go to school’ is the twentieth-century sequel to School beginnings: A nineteenth-century colonial story (2005). Together, these books provide a window into the history of schooling in New Zealand from the perspectives of the youngest children and their teachers, in the variously called preparatory, primer, infant or junior classes in primary schools, and a few infant schools. This book is about the ‘new education’ ideas that emerged around 1900, at the start of the new century, which slowly transformed the work and play of life in the classroom for young children at school. The story concludes in 2010.

Turn-of-the-century classrooms: Infants 3 and 4 girls, North East Valley School, Dunedin, 1913. HC S09234g.

Infant boys, North East Valley School, Dunedin 1913. HC S09-234f.

Clyde Quay School infants, Wellington. ANZ/w AAFL 691 4.4ab.

Te Aro School, Wellington, 1909. ANZ/w ABHO W3371.

Turn-of-the-century realities

In 1900, few of the 51,492 five, six and seven-year-old children in public and native schools would have discerned, and even fewer recalled, any change in the daily realities of their classroom life. In his recollection of starting school in Amberley, a rural Canterbury community in 1901, Rewi Alley captures the likely grimness of the school experience for some children:

I well remember the day I turned five, running up a pile of bags of chaff before my golden curls were cut off, shouting, ‘I’m a man now’ …. In the primer classes we had a mistress who was determined that every one of her charges without exception should learn. More than two mistakes in spelling or more than two sums wrong brought the strap. Coming into school with dirty knees brought the strap …. I do not think I escaped the strap on a single day in those early years. I do not think the mistress was particularly successful in teaching me to spell …. There was one day when I was strapped five times, the last offence being when I pulled my short pants high and painted my designs on my legs instead of the paper during a painting class.2

Punishment was institutionalised in European and colonial schooling traditions and its eventual demise slow. With evidence from oral histories recalling the turn of the century, historian Jeanine Graham states, ‘Far more children experienced physical violence at school than at home.’3 But the fact that Rewi had a ‘painting class’ was a clue to changes in the focus and fabric of schooling that were slowly infiltrating classroom practice. Policy documents of the period suggest a more kindly regimen and considerably more innovation. Poorly trained teachers, too many children, ill-equipped and unhealthy classrooms, and stern examination requirements were realities that frustrated endeavours to introduce new education methods intended to provide a more understanding and interesting environment for the youngest children at school.

Thirteen years later in 1914, Rewi Alley’s sister, Gwen Alley (later Somerset) began her training as a teenage pupil-teacher in the infant room at Elmwood School. Her experiences were the impetus for a life-long commitment to transform the education of young children. This later led to her leadership in the Playcentre movement:

On my first morning I found two rows of new entrants of five years seated on two forms facing each other beneath a blackboard. The room was deathly quiet except for the occasional squeak of a pencil slate. The two rows of new children sat quivering in fear of the strange world into which they had just been deposited. The Infant Mistress loomed above them. She announced, ‘The first one who cries will get this,’ and showed her strap.4

Fredric Alley, the father of Rewi and Gwen, was the head teacher of the school where Rewi got a daily strapping. While a stern disciplinarian of his children, Fredric was also known for his progressive methods and his love for literature, music and the natural environment. Recalling his fear that the inspectors would fault his focus on ‘children rather than results’, he told his daughter Gwen that ‘Father Pestalozzi might never have existed.’5 (In the early years of the nineteenth century, the Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi had promoted a kind of schooling premised on affection and engagement between teachers and children.)6

A gradual lessening of violence within the classroom did not necessarily mean peace in the playground. John Money recalled that his first day at school in 1923 was ‘abominable’ for a five-year-old ‘enthralled by the prospect of learning.’ Money described his first day at Morrinsville School in the rural North Island to historian Michael King, who wrote that he felt like

a stranger among the Lord of the Flies. He was utterly unprepared for the manner in which the Pakeha children fought with Maori children in the playground, replaying, as he saw it, the Waikato Wars of sixty years earlier (there were at the school grandchildren and great-grandchildren of men who had fought on both sides of that conflict). Local Maori members of the Ngati Haua tribe were still smarting from the confiscation of much of their land as punishment for their rebellion against the Crown.

Money sought help from his older cousin in the girl’s play shed (an open-air three-sided shed where children could eat their lunch or shelter in cold weather). However:

The girls would have nothing to do with a boy in their sanctuary [and] abandoned me to the attacking warriors. Catastrophe!7

At lunch-time John ran home, on the pretext that he thought school had finished, but was promptly returned by his mother to the classroom. He learned to absent himself from the parts of the playground ‘where combat seemed to erupt every playtime and lunchtime.’8 Money’s mother did not demand, as would later be the case, that the school protect younger children. Such protection was only for girls and in the ‘sanctuary’ of their shed. The vignette also serves as a reminder of the short time span of our schooling and colonial history. John Money died in 2006, yet his first experiences at school re-enact the central events of nineteenth-century colonial history. While encounters between Maori and Pakeha became less cataclysmic, both races used schooling and education as tools to transform and contain the turn-of-the-century demarcations in power, politics, land and language. Maori and Pakeha scholars have told these stories about their education. The many images of schools in forest clearings may be an heroic story of endeavour for Pakeha settlers, but these same forested lands were the subject of loss by Maori.

Ohuru railway camp school built by settlers in forest clearing, Whanganui district, 1909. WH scs/misc/94

In addition to documenting the changing environment for the youngest children at school, this book reveals the growing influence of women teachers, women like Alley who, as infant mistresses of their own domain, successfully demonstrated the possibilities and practicalities of a distinctly New Zealand pedagogy for early years’ schooling. This history includes the stories of infant/junior school-teachers, who were sometimes radical or misunderstood. In this regard, it is opportune to consider the opinions surrounding the country’s most famous infant mistress, Sylvia Ashton-Warner, who taught Maori infants during the middle years of the century and then wrote about the experience. By this time the infant mistress, although not Ashton-Warner, had become a powerful presence and voice in schooling matters. The lives of these women have mainly been lost in our recorded histories of schooling.

As the balance between preschool and early schooling changed in respect to a child’s introduction into the education system, the voices of advocacy for early education also changed. The earlier presence and power of the expert infant mistress was, from the 1980s, eclipsed by a cohort of nationally and internationally noted New Zealand scholars and advocates in the early childhood sector.9

New understandings

‘I am five and I go to school’ opens at the beginning of a century when the term ‘new education’ was coined. The focus, rationale and methods of new education were deemed progressive, in the sense of being a necessary tool for social reforms inten...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Youngest Children at School

- 2 Rethinking the Early Years, 1900s–1920s

- 3 Experiments and Expediency, 1910s–1930s

- 4 Politics of Playway, 1940s–1950s

- 5 Alternative Solutions, 1960s–1980s

- 6 The Measure of Juniors, 1980s–2000s

- Appendices

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover