- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Uncover the gripping story of the hunt for deadly influenza viruses and the race to unlock their secrets.

When a new influenza virus emerges, it can trigger a global pandemic with devastating consequences. Flu Hunter chronicles the relentless scientific quest to understand these viruses, revealing the high-stakes detective work behind pandemic preparedness.

Follow Robert Webster's remarkable journey as he pieces together the puzzle of influenza evolution, from remote bird habitats to cutting-edge laboratories. Discover the crucial role of international collaboration and the ever-present threat of future outbreaks. This book is for anyone interested in:

- The origins of infectious diseases

- The history of science and medicine

- The ongoing battle against global health threats

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Flu Hunter by Robert G Webster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Epidemiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

EMERGENCE OF THE MONSTER: SPANISH INFLUENZA, 1918

The virus that emerged some time in the late Northern Hemisphere summer of 1918 undoubtedly caused the most deadly influenza that humanity has ever encountered. A perfectly healthy young person at the peak of life would develop a headache and muscle soreness, their body temperature would rise as high as 41.1°C (106°F), and some people would become delirious. The person would be so weak that they would fall down; mahogany-coloured spots would appear on the face, which itself would turn blue or blackish from lack of oxygen; and the person would bleed from the ears and nose. The lungs would fill with blood and the sufferer would essentially drown in their own blood. Of the initial survivors, many would be killed by secondary bacterial pneumonia. Both sexes were equally affected, and pregnant women had a 20 per cent probability of miscarriage. In a smaller percentage of survivors, the virus may have spread to the brain, causing delirium and possibly Parkinson’s disease or encephalitis lethargica (sleeping sickness) many years later.

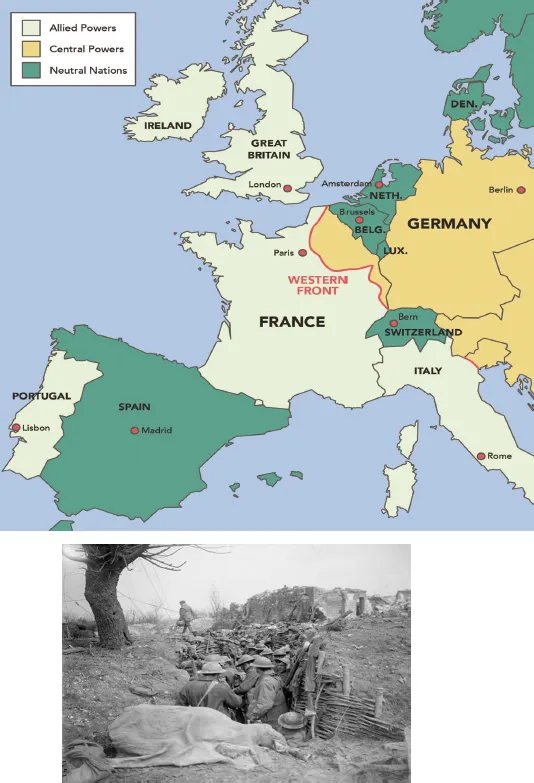

Although we do not know where the ‘monster strain’ of 1918 influenza began, World War I provided the ideal conditions for its development. By September 1918, trenches stretched across Europe from the border of Switzerland to the North Sea. Tens of thousands of soldiers on both sides of the conflict lived half underground, in cramped and often wet conditions. Hygiene was essentially non-existent, with pit latrines and scant washing facilities, and lice and rats as constant irritants (Figure 1.1).

The 1918 influenza came in three waves, the first beginning in March 1918, the second in September to November and the third in early 1919.1 The first, early in the year, was the mildest. Sufferers experienced the sudden onset of severe headaches, general muscle soreness, and fever with temperatures rising to 38.3–38.9°C (102–103°F). In most infected people, the illness lasted only about four days, but some developed pneumonia, and some died.

While this was a so-called mild wave of the disease, it had an enormous impact on trench warfare. In May 1918 the French army was removing 1500–2000 infected men per day from the front line to the rear. This meant not only that there were fewer soldiers at the front but also that all available transportation was filled, and roads and hospitals were clogged. The situation was similar for the British, Italian and German armies.

This mild strain had in fact been brought to Europe by American troops in early April 1918: unwittingly, the United States had introduced biological warfare into World War I. The German commander Erich von Ludendorff attributed the failure of the German army in the concluding battles of the war not to the superiority of the American troops and their equipment but to the influenza that the American doughboys had brought to the front lines and spread to the German troops. This is quite conceivable: the trenches of the opposing sides were only 30 metres apart in some places, and the virus may have blown across or, more likely, been spread by captured soldiers.

At least a portion of the American troops would have been exposed to this influenza virus earlier and might well have been immune, for it was first described in the small town of Haskell, Kansas, in late February 1918.2 It was spread by recruits to Camp Funston at Fort Riley, west of Kansas City, where the camp hospital received its first influenza case on 4 March 1918. Within three weeks, 1100 soldiers were hospitalised. The virus spread rapidly between military camps and to nearby towns, first to Camps Forest and Greenleaf in Georgia, where up to 10 per cent of soldiers were reported sick.3

Figure 1.1 Trench warfare in World War I. By 1918 the trenches stretched from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Soldiers fought from trenches dug deeply into the soil, and combatants on both sides were subject to poison-gas clouds.

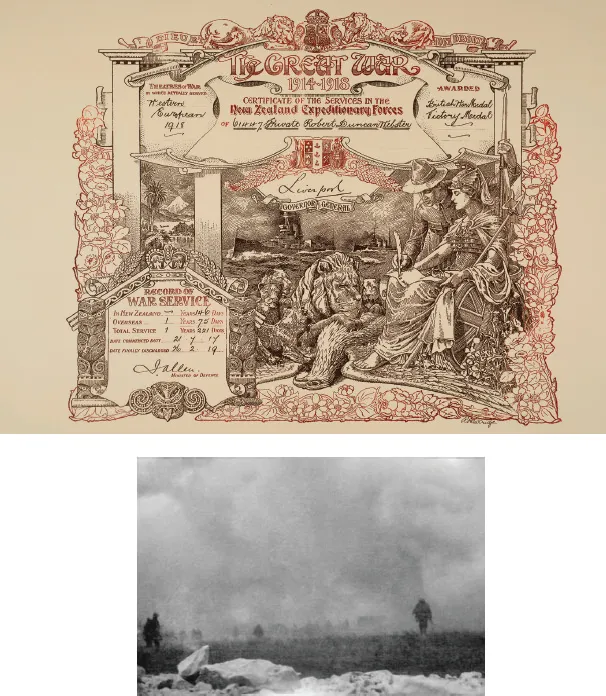

Figure 1.2 Robert Duncan Webster, my father, fought with the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces in the trenches in France, and was wounded in the 100-day offensive in 1918. Like many soldiers, he experienced the deadly gas cloud.

It was inevitable that the ships carrying the first deployment of American troops to Europe would have the virus on board. These vessels were carrying twice as many soldiers as they were designed for, with men sleeping two to a bunk in shifts – ideal conditions for the virus to spread. Because neither the severity nor the fatality rate was particularly high, however, no alarm bells sounded. But in August and September of that year, a second, ‘killer’ strain of influenza emerged on the return voyages to the United States, turning shipboard life into what was described as ‘Hades of Hell’, with soldiers vomiting blood.4 Nevertheless, the American fleet had a lower mortality rate than any other American military group – 6.43 per cent among the troops and 1.5 per cent among the crew – probably because of their earlier exposure to the first wave of influenza.

Besides the horrendous overcrowding and poor hygiene in the trenches of Europe in 1918, there is another reason to believe that the trenches were the probable site of the emergence of the monster strain of 1918 influenza. There was widespread use of poisonous gases, which not only affected the troops directly but could also have caused the influenza virus to mutate and become more lethal.

Despite the Hague Convention of 1907 banning the use of chemical weapons in warfare, poisonous gases were used by both sides in World War I. Since Germany had the largest chemical industry, it is not surprising that it was the heaviest user, but it was not alone. The usage peaked when influenza was circulating among soldiers at the front line. The main chemical agents included chlorine gas, phosgene gas and mustard gas. Although the chemical weapons were not often lethal, they debilitated the troops, causing blisters, blindness and respiratory problems. Incoming supply lines of ammunition, food and fresh troops were blocked by the large numbers of blind and wounded men being led to the rear of the battle zones. Chlorine gas was also an effective psychological weapon – the sight of an incoming cloud of gas became a source of dread to the infantry. My own father was one of the soldiers who experienced the fearful gas cloud (Figure 1.2).

Both phosgene and mustard gas are known mutagenic agents, substances that can cause cells to make mistakes when replicating their DNA. In the laboratory we use mutagenic agents to deliberately change an influenza virus in order to understand the genetic code responsible for reduced or increased disease potential. In the trenches the exposure of virus-infected soldiers to mustard gas could have had the same effect, converting the virus from a relatively mild influenza strain into a killer. Trenches full of thousands of debilitated men would have been the perfect breeding ground for such a virus once it had emerged.5

While we will never know exactly where the mutated killer strain of the virus emerged, once it did, it spread quickly to combatants on both sides of the conflict, back down the supply chains to people in nearby towns and cities and then around the world. During the closing battles of World War I, both sides were badly affected. During the milder wave, 10 to 25 per cent of the French troops had to be evacuated from the front line; during the severe wave, the figure rose to 46 per cent. The German war machine was badly affected too.

News of outbreaks of infection among soldiers, sailors and military support personnel was kept quiet by both sides for tactical reasons, with the result that members of the public were deliberately kept in the dark about this imminent threat to their own welfare. It was considered unpatriotic to write anything that might impede the war effort. This code of secrecy extended from public officials to newspapers to the top levels of government and the military. President Woodrow Wilson, who was kept informed of the outbreaks from March 1918 onwards, was persuaded that news of the death rates on troopships en route to Europe had to be kept quiet so as not to jeopardise the war effort.

The milder influenza hit the headlines in late May 1918, when King Alfonso XIII of Spain and his cabinet members became infected. Since Spain was neutral in World War I, there were no restrictions on publishing this information. The outbreak was reported in Madrid’s newspapers as not severe, lasting about four days with no deaths. In October, however, Spain was hit with the second strain and its high mortality rate.6 Because these first reports of the outbreak occurred in Spain, the pandemic (worldwide epidemic) that ensued was dubbed Spanish influenza.

The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I and specified the reparations to be paid to the Allied nations by Germany, was signed in Paris in April 1919. At this conference the ‘Big Four’ (the prime ministers of France, Britain and Italy and the president of the United States) called the shots. President Wilson wanted Germany to be allowed to retain some resources to aid its economic recovery, but Georges Clemenceau of France (‘the Tiger’) wanted Germany severely and humiliatingly punished. Wilson threatened to walk out, and then, at the most critical stage of negotiations, he contracted the influenza virus. His young aide, Donald Ferry, was infected on 3 April and died four days later. The president’s wife, daughter and other aides were also severely affected. President Wilson survived but with a markedly changed personality. It is possible that the virus damaged his brain; this was one of the sequelae of the monster virus. From his sickbed, Woodrow Wilson capitulated to all of Clemenceau’s demands regarding German reparations,7 which saw Germany sink into a severe economic depression. Whether Wilson’s infection was the cause of his changed stance cannot be known.

The worldwide death toll from the Spanish influenza was reported as between 24.7 and 39.3 million but may have been as high as 100 million. The societal disruption and population reduction worldwide were catastrophic.

TWO DISTANT CITIES, TWO APPROACHES

The terrifying impact of the second wave of Spanish influenza was similar in widely disparate places around the world. Events in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the United States, and in Auckland, New Zealand, serve to illustrate the similarities.

Philadelphia

The virus arrived in the port city of Philadelphia on 7 September 1918 with 300 sailors from Boston. The severe strain had surfaced in Boston on 27 August 1918; it was thought to have been brought back from Brest, France. Medical facilities in Philadelphia were quickly overwhelmed, and severely ill sailors began to die: one on the first day, 11 on the second; then the nurse who had tended the first sailor died, and the virus seeded the city.

A huge Liberty Loan parade to raise millions of dollars to support the war effort had been scheduled for 28 September, and despite dire warnings from university and military health officials about the risk of the disease spreading in the crowds, the event went ahead. The parade of sailors, soldiers, marines, boy scouts and women’s auxiliary organisations stretched for three kilometres, with thousands watching. Two days later the 31 hospitals in Philadelphia were overflowing with the sick and dying.

By 1 October, three days after the parade, 117 people were dead. All public gatherings were banned, and emergency hospitals were set up. Ten days after the parade, hundreds were dying every day, with thousands afflicted. Symptoms included nosebleeds, cyanosis and delirium. As the supply of coffins ran out, bodies were banked up at funeral homes, and more bodies decayed in houses.

The onslaught peaked in the week of 19 October, when over 4500 people died. Then the death toll declined quite rapidly, and by 25 October the emergency hospitals began to close down. Schools reopened on 28 October. A false report of armistice with Germany on 7 November brought huge crowds hugging and kissing onto the streets of Philadelphia, but there was no resurgence of influenza. The huge celebration was repeated on Armistice Day, 11 November, and once more there was no renewed outbreak.

Researchers in Philadelphia isolated a bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae, from the lungs of sufferers and believed this to be the cause of the deadly disease. A vaccine based on the bacterium was developed by health officials and released on 19 October: over 10,000 doses were given to city services personnel. Since the vaccine was given during the waning phase of the pandemic, it appeared effective. It probably also served to calm the fears of the community. But over the 27 weeks of the pandemic, more than 15,700 people died in Philadelphia, with the highest death toll in the 25–34 age group.

Auckland

On the other side of the world in Auckland, New Zealand, the introduction, spread and severity of the highly deadly 1918 Spanish influenza were similar in many ways. The introduction of the virus to New Zealand is controversial. The steamship Niagara, which carried New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey home f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Lance Jennings

- CHAPTER 1. Emergence of the monster: Spanish influenza, 1918

- CHAPTER 2. The start of influenza research

- CHAPTER 3. From seabirds in Australia to Tamiflu

- CHAPTER 4. The search moves to wild ducks in Canada

- CHAPTER 5. Delaware Bay: The right place at the right time

- CHAPTER 6. Proving interspecies transmission

- CHAPTER 7. Virologists visit China

- CHAPTER 8. Hong Kong hotbed: Live bird markets and pig processing

- CHAPTER 9. Searching the world, 1975–95

- CHAPTER 10. The smoking gun

- CHAPTER 11. Bird flu: The rise and spread of H5N1

- CHAPTER 12. The first pandemic of the 21st century

- CHAPTER 13. SARS, and a second bird flu outbreak

- CHAPTER 14. Digging for answers on the 1918 Spanish influenza

- CHAPTER 15. Resurrecting the 1918 Spanish influenza

- CHAPTER 16. Opening Pandora’s Box

- CHAPTER 17. Looking to the future: Are we better prepared?

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index