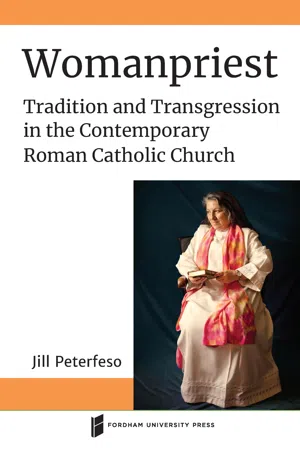

Womanpriest

Tradition and Transgression in the Contemporary Roman Catholic Church

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book is openly available in digital formats thanks to a generous grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. While some Catholics and even non-Catholics today are asking if priests are necessary, especially given the ongoing sex-abuse scandal, The Roman Catholic Womanpriests (RCWP) looks to reframe and reform Roman Catholic priesthood, starting with ordained women. Womanpriest is the first academic study of the RCWP movement. As an ethnography, Womanpriest analyzes the womenpriests' actions and lived theologies in order to explore ongoing tensions in Roman Catholicism around gender and sexuality, priestly authority, and religious change.In order to understand how womenpriests navigate tradition and transgression, this study situates RCWP within post–Vatican II Catholicism, apostolic succession, sacraments, ministerial action, and questions of embodiment. Womanpriest reveals RCWP to be a discrete religious movement in a distinct religious moment, with a small group of tenacious women defying the Catholic patriarchy, taking on the priestly role, and demanding reconsideration of Roman Catholic tradition. Doing so, the women inhabit and re-create the central tensions in Catholicism today.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Called

Honoring the Call, Not the Church

it is sometimes said and written in books and periodicals that some women feel they have a vocation to the priesthood. Such an attraction, however noble and understandable, still does not suffice for a genuine vocation. In fact a vocation cannot be reduced to a mere personal attraction, which can remain purely subjective.6

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 Called

- CHAPTER 2 Rome's Mixed Messages

- CHAPTER 3 Conflict and Creativity

- CHAPTER 4 Ordination

- CHAPTER 5 Sacraments

- CHAPTER 6 Ministries on the Margins

- CHAPTER 7 Womenpriests' Bodies

- Conclusion

- APPENDIXES

- Acknowledgments

- Notes