1

China Girls in the Film Laboratory

Before my eyes—there, passing in slow procession along the wheeling cylinders, I seemed to see, glued to the pallid incipience of the pulp, the yet more pallid faces of all the pallid girls I had eyed that heavy day. Slowly, mournfully, beseechingly, yet unresistingly, they gleamed along, their agony dimly outlined on the imperfect paper, like the print of the tormented face on the handkerchief of Saint Veronica.

—HERMAN MELVILLE, “THE TARTARUS OF MAIDS”1

The most ubiquitous woman in film has hardly ever been seen. This woman, often conflated with the name for the China Girl reference image, was for the majority of film history used in quality control procedures in film laboratories. However prominent behind the scenes, the China Girl rarely made it to the cinema screen. As John Pytlak, a former Kodak engineer who pioneered the Laboratory Aim Density China Girl image, described, “she has probably been in more movies than any other actress in the world.”2 Yet the China Girl, though crucial to the final look of a film, and common across commercial film production worldwide, remains unknown.

The China Girl appears in every country that has a major film industry, including the United States, France, Germany, Italy, China, Korea, Japan, and India. In Western nations, the China Girl model is almost always female, young, conventionally attractive, and, despite the racial connotations of the name, white. The China Girl can be found on the ends of the film reel, with a few frames cut into either the head or tail leader. On 16 mm or 35 mm film, three to six China Girl frames are typically cut into the countdown leader, normally between the numbers 10 and 3. Its appearance on a release print is an artifact of developing and printing processes by which it had been used to calibrate exposure, density, and color, particularly ideal values for skin tone, as well as the machines by which these values are set. The China Girl functions primarily in a feedback system, where the image tests for quality control in the making of master and positive elements from edited film negatives, the duplication of positive prints, and the mass production of release prints, among many other uses.

Strictly speaking, the China Girl is a reference image not to be mistaken with the many anonymous women who posed as “China Girls.” The singular China Girl is an object, a tool used in film laboratories and an emblem of the production process in which it partakes, while the plural form fits into a history of female labor in the film industry. This distinction is important for the way this figure is understood both historically and conceptually. Pytlak’s romanticized remarks above indicate how easily one can slide between these two terms. By posing as China Girls, women are made into the China Girl reference image, a transformation from she to it, and from female body to material for film. This process happens far below a film viewer’s awareness. A China Girl would only appear during a screening if a projectionist failed to switch film reels at the correct moment; even then the short duration of its fugitive appearance would be just as easy to miss. Save the projectionist’s error, there is, of course, no explicit prohibition against seeing the China Girl, though glimpsing it runs the momentary risk of disrupting a movie’s narrative reverie by literally exposing the constitutive seams of a film’s construction. The China Girl is generally only known to those that handle and scrutinize film, chiefly laboratory technicians and archivists. The women who posed as China Girls disappear twice over: first as the China Girl image on the film leader that are overlooked by viewers, and second as the anonymous laborers whose behind-the-scenes work, like many others, goes under-recognized by film historians and enthusiasts in favor of the achievements of actors, directors, and other above-the-line talents.

The image has been in use since the early to mid-1920s, and it remained a central part of laboratory culture throughout the twentieth century. Though today the photochemical processing of film has nearly ceased in commercial film production, the China Girl and the quality control methods associated with it continue in limited application, especially in hybrid processes requiring film-to-digital conversions. As this chapter shows, the first decades of its use were crucial in establishing a gendered and vaguely racialized practice that formed the basis for the appearance of all film. The China Girl is more than just a woman’s face but an instrumentalized image whose values for tone, density, and color are broken down, isolated, and abstracted to establish the material basis for other images. In the China Girl, material is inextricable from image—it is indeed constitutive of it. Specifically, the China Girl delineates the material conditions of laboratory processes, which, however scientific, were for the majority of the twentieth century manually executed and always in need of adjustment.

As a technical image, the China Girl is far from neutral. Despite the rhetoric of objectivity used to describe laboratory processes in trade journals, the image yokes prevailing cultural notions of race, gender, and sexuality to technical function and practice. In a perhaps unconscious way, the China Girl imports a complex matrix of cultural assumptions to the terrain of filmic representation and its material basis. As with any technology, of course, film can never be presumed to be innocent of the cultural conditions in which it was developed and practiced. Technology can only function within a cultural logic. Like the computing technologies that for Tara McPherson invoke “operating systems of a larger order,” film is crucial to the way culture understands and organizes its constituents and their images.3 Though rarely seen by typical film viewers, the China Girl image has been necessary to the ongoing function of the film laboratory. The techniques fundamental to film production conceived of filmic materiality in terms of a woman’s body. This is not just an empirical claim—although it would cover all cases of commercially produced film. What interests me is how the woman’s body, while not specifically necessary to film production processes, has been incorporated into them by laboratory technicians, and how the China Girl has been made crucial to these procedures. Here it is important to draw a distinction between the practical, standardizing function of the China Girl for film and the way these materials have been historically understood as part of a filmic imaginary.

The China Girl is distinct from the referential or representational quality of the types of images that appear onscreen in that it is regarded only as a technical tool, used to calibrate other images. On a strictly technical level, the reference image need not depict a woman at all. In the China Girl’s technical capacity, the body of the model disappears—subordinated, along with other laboratory and postproduction procedures, to a regime that privileges the luminous faces of actors onscreen. It remains behind the scenes, overlooked. Yet, because of its perceived utility, it has survived as an unusually durable figure.4

The woman’s body is, in effect, a means of production consumed to produce a “correct” appearance for images onscreen. In this sense the China Girl is no different from the standardization tests and procedures one would find in, say, industrial iron smelting. The test image is simply another cost of production, folded into the laboratory’s operating budget. We are accustomed to thinking about images as cultural objects rather than as functional technical components. Photographs of individuals automatically tend to signify particularity, but individuality makes up no part of the use-value of the China Girl, in Marx’s sense. Although the China Girl is a film image of a woman’s face, it is nonsignifying and kept outside the domain of representation. From the point of view of industry, any signifying feature should be considered a kind of semiotic excess along the lines of the capitalist imagined by Marx with “a foible for using golden spindles instead of steel ones.”5 It is a nonscenic element, consigned to the ends of the filmstrip, different even than the diegetic contiguity suggested by offscreen space. The face of the China Girl is nonmimetic, and for this reason, it cannot appear in the manner of other film images. Instead it is understood as raw material for the production of film, with only a trace left on its unseen margins. Even if the China Girl is profilmic in the sense that it is an arrangement of elements before a camera, it indicates how the film laboratory functions as another kind of “studio” in which an alternative economy of images circulates. The China Girl is a condition of industrial film production, rather than a “film” in its own right.

By this same logic, the bodies of the women who posed as models have remained even further from the picture. As regards the women who posed as China Girls, they have all but vanished, lost to countless hours of uncredited and anonymous labor. While I have been fortunate to track down a small number of former models, as I will discuss later in this chapter, it is difficult to locate China Girl models since their images often migrate from one film to another in the process of reduplication and quality-control testing.6 The China Girl is a somewhat apocryphal figure. Though many within the more technical sectors of the film industry express familiarity or, as is frequently the case, longtime fascination regarding the China Girl, there is not, to my knowledge, a confirmed written account that describes either the first usage of a China Girl nor the origins of the name.

As the name suggests, the China Girl encodes attitudes about race. China Girls are often attended by orientalist details in dress, hairstyle, and as reported in some cases, a straw “Coolie” hat.7 In the 1970s, for example, Kodak posed many of its China Girl models in the same mandarin-collared blouse (one of these can be seen in Mark Toscano’s Releasing Human Energies, discussed later in this chapter). China is also suggested in the material of porcelain, as in china or porcelain dolls. The China in the term is like the name China itself, a name synonymous with its famed export, porcelain. (The word China is the invention of European traders, a phonetic approximation of the Tang Dynasty’s center of porcelain production Changnan, or present-day Jingdezhen.) The linking of race, gender, and material is also apparent in the various names given to the China Girl in countries outside of the United States: in France, it is known as “Lili,” “la chinoise,” “Kodakette,” and “la bridée,” with the latter referring to the slanted shape of Asian eyes. In Thailand, “Muay” or “Ar Muay” is used, also referring to the appearance of a Chinese girl. Japanese technicians employ “China Girl” as an English-language phrase, as do laboratory workers in India and Slovenia (where she is also called “kitajka,” or Chinese woman). Mexico uses “muñeca” or “mona,” both of which refer to dolls, and the similar term “muñeca de porcelana” in Argentina. Laboratories in Austria refer to them as “Conchita,” which in Spanish means little shell and is also slang for “little cunt.” (Conchita is the name of the main female character in Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire [1977], and she is played by two different actresses, further underscoring the incidental quality of the woman’s actual appearance.) More broadly, this orientalism is suggested in the stereotypical notion of Asian femininity that women be subordinate and submissive, qualities that would be useful for the technological function the image serves.

Asianness as such is subordinated to gender and materiality. In western countries, China Girls are white and pale-skinned. Asian women only appear as China Girls in Asian contexts like the Japanese film industry, and even in those cases the preference for light skin prevails. Some have suggested that Asian women posed as the first China Girls, though in the wealth of China Girl images that crop up in film archives, I have yet to find evidence to back up this claim. Instead, race is reduced to oriental embellishment, eroticism, and exoticism in the China Girl name, appearance, and apocryphal origin. Within the marginal figure of the China Girl there is a further concealment of racialized bodies that do not meaningfully appear at any level. As Karen Redrobe observes about the figure of the vanishing lady in cinema, the emphasis on the spectacle of a disappearing white woman often served to conceal other kinds of missing bodies, namely the racialized subjects of colonial England.8 With Redrobe, we should remain attentive to the ways the China Girl, although marginal, can screen other figures from view.

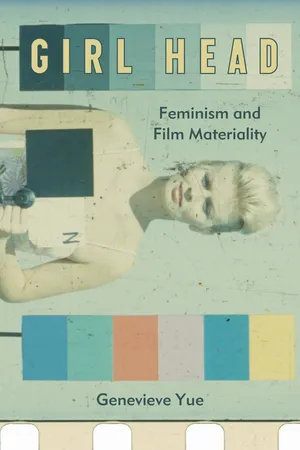

The image’s history is largely vernacular. The authors of the technical literature preferred descriptions of the sensitometry practices and instruments for which the China Girl was employed over mentions of the image itself. The first reference to a “close-up of a girl” does not occur in the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, the chief professional journal for the film industry until 1933, though the densitometer, the instrument most closely associated with the China Girl, first appeared in the journal in 1923. “Gray lily card,” another synonym, first appears in a 1958 article. “China Girl” and “girl head” (and its variant “head girl”) are only used in the journal beginning in the early seventies, though they had long been used in film laboratory vernacular.9 It is more common for technical literature and cinematography and laboratory manuals to write “test strips,” “control strips,” “picture tests,” “test pieces,” or “sample printing,” though not all of these necessarily indicate a process that has a face.10

A rare acknowledgement of China Girls occurs in a 1967 ad thanking “The Group” at Kodak (fig. 7). The image features four white women dressed in a range of attire: wedding gown, black lingerie, slacks and flat-heeled shoes, and cocktail dress, They are posed in a living room set, with the lighting and motion picture camera of the backstage area visible. The ad is startlingly aware of the peripheral place these women typically occupy:

Before any Hollywood starlet gets her big chance in a new film, these girls at Kodak have seen thousands of images of themselves. On the same type film! Such is life at Kodak—we do a terrific amount of testing before we put our best footage forward. And what better subjects for our screen testing than these four lovely girls? … Thanks, girls, for your splendid efforts in movies that will never put your names up in lights. But you knew all along: your roles were played only in the name of progress.11

While technical histories documenting the development of film stocks or standardization methods for the film industry abound, the China Girl remains largely absent from film scholarship in a manner not dissimilar from her marginal place on the filmstrip.12 As a projectionist at the George Eastman Museum said to me during one of my visits to the research library, “you’re looking for exactly what we’re trained to ignore.” The China Girl serves, somewhat emblematically, as a mute, subservient, female foil against the male-dominated accomplis...