![]()

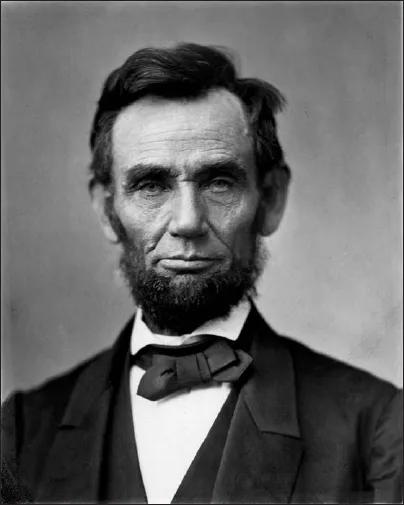

Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln in November 1863

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865) was an American statesman and lawyer who served as the 16th president of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln led the nation through the American Civil War, its bloodiest war and its greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis.[2][3] He preserved the Union, abolished slavery, strengthened the federal government, and modernized the U.S. economy.

Born in Kentucky, Lincoln grew up on the frontier in a poor family. Self-educated, he became a lawyer, Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator, and Congressman. In 1849, he left government to resume his law practice, but angered by the Kansas–Nebraska Act’s opening of the prairie lands to slavery, reentered politics in 1854. He became a leader in the new Republican Party and gained national attention in the 1858 debates against national Democratic leader Stephen Douglas in the U.S. Senate campaign in Illinois. He then ran for President in 1860, sweeping the North and winning. Southern pro-slavery elements took his win as proof that the North was rejecting the constitutional rights of Southern states to practice slavery. They began the process of seceding from the union. To secure its independence, the new Confederate States of America fired on Fort Sumter, one of the few U.S. forts in the South. Lincoln called up volunteers and militia to suppress the rebellion and restore the Union.

As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican Party, Lincoln confronted Radical Republicans, who demanded harsher treatment of the South; War Democrats, who rallied a large faction of former opponents into his camp; anti-war Democrats (called Copperheads), who despised him; and irreconcilable secessionists, who plotted his assassination. Lincoln fought the factions by pitting them against each other, by carefully distributing political patronage, and by appealing to the American people.[4]:65–87 His Gettysburg Address became an iconic call for nationalism, republicanism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. He suspended habeas corpus, and he averted British intervention by defusing the Trent Affair. Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, including the selection of generals and the naval blockade that shut down the South’s trade. As the war progressed, he maneuvered to end slavery, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863; ordering the Army to protect escaped slaves, encouraging border states to outlaw slavery, and pushing through Congress the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which outlawed slavery across the country.

Lincoln managed his own re-election campaign. He sought to reconcile his damaged nation by avoiding retribution against the secessionists. A few days after the Battle of Appomattox Court House, he was shot by John Wilkes Booth, an actor and Confederate sympathizer, on April 14, 1865, and died the following day. Abraham Lincoln is remembered as the United States’ martyr hero. He is consistently ranked both by scholars[5] and the public[6] as among the greatest U.S. presidents.

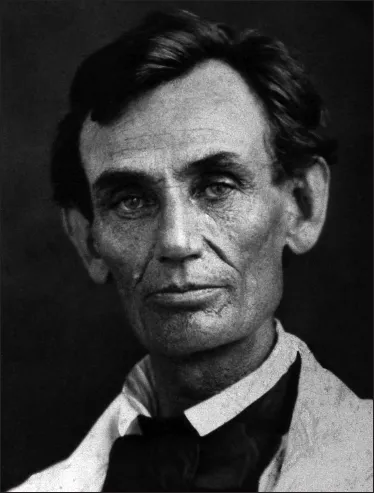

Emergence as Republican leader

Lincoln in 1858, the year of his debates with Stephen Douglas over slavery.

The debate over the status of slavery in the territories exacerbated sectional tensions between the slave-holding South and the free North. The Compromise of 1850 failed to defuse the issue.[12]:175–176 In the early 1850s, Lincoln supported sectional mediation, and his 1852 eulogy for Clay focused on the latter’s support for gradual emancipation and opposition to “both extremes” on the slavery issue.[12]:182–185 As the 1850s progressed, the debate over slavery in the Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory became particularly acrimonious, and Senator Douglas proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise measure; the proposal would allow the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery. The proposal alarmed many Northerners, who hoped to prevent the spread of slavery into the territories. Despite this Northern opposition, Douglas’s Kansas–Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.[12]:188–190

For months after its passage, Lincoln did not publicly comment, but he came to strongly oppose it.[12]:196–197 On October 16, 1854, in his “Peoria Speech,” Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency.[18]:148–152 Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a powerful voice,[12]:199 he said the Kansas Act had a “declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world . . . ”[41]:255 Lincoln’s attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.[12]:203–205

Nationally, the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting the demise of his party, Lincoln wrote in 1855, “I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist [ . . . ] I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery.”[12]:215–216 Drawing on the antislavery portion of the Whig Party, and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members, the new Republican Party formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery.[43]:38–39 Lincoln resisted early recruiting attempts, fearing that it would serve as a platform for extreme abolitionists.[12]:203–204 Lincoln hoped to rejuvenate the Whigs, though he lamented his party’s growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing movement.[12]:191–194

In the 1854 elections, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but declined to take his seat.[12]:203–205 In the elections’ aftermath, which showed the power and popularity of the movement opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Lincoln instead sought election to the United States Senate.[12]:204–205 At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature.[35]:119 After leading in the first six rounds of voting, he was unable to obtain a majority. Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat, and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln’s decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull’s antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.[12]:205–208

1856 campaign

In part due to the ongoing violent political confrontations in Kansas, opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act remained strong throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln joined the Republicans. He attended the May 1856 Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform asserted that Congress had the right to regulate slavery in the territories and called for the immediate admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention, in which he endorsed the party platform and called for the preservation of the Union.[12]:216–221 At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, Lincoln received significant support to run for vice president, though the party nominated William Dayton to run with John C. Frémont. Lincoln supported the Republican ticket, campaigning throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Ambassador James Buchanan, who had been out of the country since 1853 and thus had avoided the slavery debate, while the Know Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore.[12]:224–228 Buchanan defeated both his challengers. Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois. Lincoln’s vigorous campaigning had made him the leading Republican in Illinois.[12]:229–230

Principles

Eric Foner (2010) contrasts the abolitionists and anti-slavery Radical Republicans of the Northeast, who saw slavery as a sin, with the conservative Republicans, who thought it was bad because it hurt white people and blocked progress. Foner argues that Lincoln was a moderate in the middle, opposing slavery primarily because it violated the republicanism principles of the Founding Fathers, especially the equality of all men and democratic self-government as expressed in the Declaration of Independence.[33]:84–88

Dred Scott

In March 1857, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote that blacks were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North.[12]:236–238 Lincoln denounced it, alleging it was the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power.[53]:69–110 Lincoln argued, “The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended ‘to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity,’ but they ‘did consider all men created equal—equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”[54]:299–300

Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

Douglas was up for re-election in 1858, and Lincoln hoped to defeat him. With the former Democrat Trumbull now serving as a Republican senator, many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln’s 1856 campaigning and willingness to support Trumbull in 1854 had earned him favor.[12]:247–248 Some eastern Republicans favored Douglas’s re-election in 1858, since he had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state.[35]:138–139 Many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the nomination with little opposition.[12]:247–250

Accepting the nomination, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, drawing on Mark 3:25, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”[12]:251 The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion.[36]:98 The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas.[7]:209 When informed of Lincoln’s nomination, Douglas stated, “[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party . . . and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won.”[12]:257–258

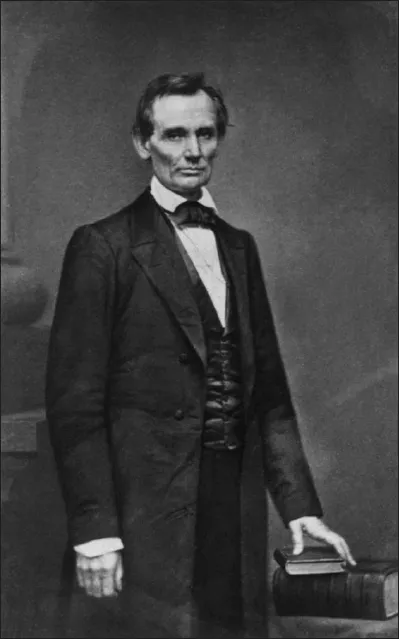

Abraham Lincoln (1860) by Mathew Brady, taken the day of the Cooper Union speech.

The Senate campaign featured seven debates, the most famous political debates in American history.[55]:182 The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that “The Slave Power” was threatening the values of republicanism, and accused Douglas of distorting the values of the Founding Fathers that all men are created equal, while Douglas emphasized his Freeport Doctrine, that local settlers were free to choose whether to allow slavery, and accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.[7]:214–224 The debates had an atmosphere of a prize fight and drew crowds in the thousands. Lincoln’s argument was rooted in morality. He claimed that Douglas represented a conspiracy to extend slavery to free states. Douglas’s argument was legal, claiming that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Dred Scott decision.[7]:223

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas. Lincoln’s articulation of the issues gave him a national political presence.[56]:89–90 In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper that was consistently supportive; most of the state’s 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but the German-language paper mobilized Republican support.[7]:242, 412 In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate, rivaled by William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast, and was unsure whether to seek the office.[12]:291–293 In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the nomination if offered, and in the following months several local papers endorsed his candidacy.[12]:307–308

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans. Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery...