- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Quantum Mechanics in Simple Matrix Form

About this book

This elementary text introduces basic quantum mechanics to undergraduates with no background in mathematics beyond algebra. Containing more than 100 problems, it provides an easy way to learn part of the quantum language and apply it to problems.

Emphasizing the matrices representing physical quantities, it describes states simply by mean values of physical quantities or by probabilities for possible values. This approach requires using the algebra of matrices and complex numbers together with probabilities and mean values, a technique introduced at the outset and used repeatedly. Students discover the essential simplicity of quantum mechanics by focusing on basics and working only with key elements of the mathematical structure--an original point of view that offers a refreshing alternative for students new to quantum mechanics.

Emphasizing the matrices representing physical quantities, it describes states simply by mean values of physical quantities or by probabilities for possible values. This approach requires using the algebra of matrices and complex numbers together with probabilities and mean values, a technique introduced at the outset and used repeatedly. Students discover the essential simplicity of quantum mechanics by focusing on basics and working only with key elements of the mathematical structure--an original point of view that offers a refreshing alternative for students new to quantum mechanics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 A STRANGE EQUATION

Quantum mechanics is the new language physicists use to describe the things the world is made of and how they interact. It is the basic language of atomic, molecular, solid-state, nuclear, and particle physics. Once found, it was developed quickly, then extended and applied with continuing success as each new area of physics grew. It emerged after a quarter century of work in atomic physics in which experiments revealed properties of the atomic world that could not be understood with the existing theories and led physicists into new ways of thinking.

The first steps toward the new language were taken in 1925 by Werner Heisenberg, then Max Born and Pascual Jordan, those three in collaboration, and Paul Dirac. Born was one of the first people to appreciate what was happening. He expected a new mathematical language, a “quantum mechanics,” would be needed for atomic physics, and he had the mathematical knowledge to develop it [1–3]. At 42, Born was an established physicist, a professor at Gottingen. Heisenberg, who was 23, had finished his doctoral studies with Arnold Sommerfeld at Munich and had come to Gottingen to work as Born’s assistant. Here is part of Born’s recollections.‡

In Göttingen we also took part in the attempts to distill the unknown mechanics of the atom out of the experimental results. The logical difficulty became ever more acute. … The art of guessing correct formulas… was brought to considerable perfection. …

This period was brought to a sudden end by Heisenberg… . He… replaced guesswork by a mathematical rule. … Heisenberg banished the picture of electron orbits with definite radii and periods of rotation, because these quantities are not observable; he demanded that the theory should be built up by means of quadratic arrays… of transition probabilities…. To me the decisive part in his work is the requirement that one must find a rule whereby from a given array… the array for the square… may be found (or, in general, the multiplication law of such arrays).

By consideration of … examples… he found this rule…. This was in the summer of 1925. Heisenberg… took leave of absence… and handed over his paper to me for publication….

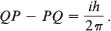

Heisenberg’s rule of multiplication left me no peace, and after a week of intensive thought and trial, I suddenly remembered an algebraic theory…. Such quadratic arrays are quite familiar to mathematicians and are called matrices, in association with a definite rule of multiplication. I applied this rule to Heisenberg’s quantum condition and found that it agreed for the diagonal elements. It was easy to guess what the remaining elements must be, namely, null; and immediately there stood before me the strange formula

This is one of the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics. In it Q represents a position coordinate of a particle, P represents the momentum of the particle in the same direction, and i and h are fixed numbers. For an electron in a hydrogen atom, typical values for Q and P are 5 X 10 –9 cm and 2 X 10 –9 g . cm/s. These are small but otherwise ordinary physical quantities.

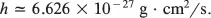

Then shouldn’t QP be the same as PQ? This equation says they are not the same. That is indeed strange. The number h, which is called Planck’s constant, is

That is very small, so the equation says the difference between QP and PQ is small, but not zero.

There is something else that is strange in this equation. The number i has the property that

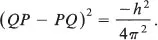

so taking the square of both sides of the equation gives

Isn’t the square of any number positive? How can the square of QP — PQ be negative? We see there are some things that have to be learned before all this can be understood. We will consider the question about squares first and then come back to the question of how QP can be different from PQ.

We can also begin to see that the quantum language gives us a new view of the world. We shall find many features of it that differ from everyday experience and even from common sense. They represent an extension of human knowledge to a much smaller scale of size, to atoms and atomic particles. Nothing as small as Planck’s constant would ever be noticed in everyday life. Quantum mechanics is one of the most important and interesting accomplishments of science, but it is not part of our common knowledge. It has been used for over half a century but still, for each of us who learns it, it is strange and wonderful.

REFERENCES

‡From Ref. Ref 4. © The Nobel Foundation, 1955.

1.M. Born, Z. Phys. 26, 379 (1924). An English translation is reprinted in Sources of Quantum Mechanics, edited by B. L. van der Waerden. Dover, New York, 1968, pp. 181-198.

2.J. Mehra and H. Rechenberg, The Historical Development of Quantum Theory, Volume 2, The Discovery of Quantum Mechanics 1925, p. 71, and Volume 3, The Formulation of Matrix Mechanics and Its Modifications 1925-1926, p. 44. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1982.

3.D. Serwer, “Unmechanischer Zwang: Pauli, Heisenberg, and the Rejection of the Mechanical Atom, 1923-1925,” in Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences, Vol. 8, edited by R. McCormmach and L. Pyenson. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1977, particularly pp. 194-195.

4.M. Born, Science 122, 675-679 (1955). This is an English translation of Bern’s Nobel lecture. I have rewritten the equation in the notation we will use here.

2 IMAGINARY NUMBERS

The number i such that

i2 = –1

is called an imaginary number. Inventing it did take some thought and imagination.

Consider the familiar numbers. There are positive numbers su...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Summary

- 1. A Strange Equation

- 2. Imaginary Numbers

- 3. Matrices

- 4. Pauli Matrices

- 5. Vectors

- 6. Probability

- 7. Basic Rules

- 8. Spin And Magnetic Moment

- 9. Sunrise And First View

- 10. All Quantities Made From Spin

- 11. Non-Negative Quantities

- 12. What Can be Measured

- 13. General Rules

- 14. Two Spins

- 15. Einstein’s Instincts

- 16. Bell’s Inequalities

- 17. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Relation

- 18. Quantized Oscillator Energy

- 19. Bohr’s MOdel

- 20. Angular Momentum

- 21. Rotational Energy

- 22. The Hydrogen Atom

- 23. Spin Rotations

- 24. Small Rotations

- 25. Changes in Space LOcation

- 26. Changes in Time

- 27. Changes in Velocity

- 28. Invariance And What it Implies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Quantum Mechanics in Simple Matrix Form by Thomas F. Jordan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.