![]()

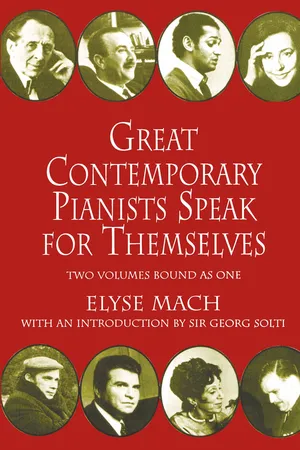

GREAT CONTEMPORARY PIANISTS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

ELYSE MACH

VOLUME 1

![]()

TO AUNT LISA

You see my piano is for me what his frigate is to a sailor, or his horse to an Arab—more indeed: it is my very self, my mother tongue, my life. Within its seven octaves it encloses the whole range of an orchestra, and a man’s ten fingers have the power to reproduce the harmonies which are created by hundreds of performers.

Franz Liszt, in an open letter to Adolphe Pictet, written in Chambéry, September 1837, and published in the Gazette musicale of February 11, 1838

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EVERY book is the product of the thought and work of many people, and I am especially grateful to those individuals whose generous help has made this book possible. Special acknowledgments go to Allen Klots, my editor, for his encouragement, pertinent suggestions, and professional expertise on the preparation of this manuscript; to Robert Silverman, editor and publisher of The Piano Quarterly, for his immeasurable help and advice on various phases of this project, and for granting permission to reprint excerpts of my earlier interview with Vladimir Horowitz, and an excerpt from Brede and Gloria Ackerman’s interview with André Watts; to my dear friends and colleagues Anthony Brenner, Chicago City College, Ann and David Pope, Bowling Green State University, and William Schutt, Northeastern Illinois University, for their valuable help on the interviews and incisive comments on the manuscript; to the directors and staffs of the artist managements and personal managements, namely, Herbert Barrett Management, Herbert Breslin, Inc., Colbert Artists, Columbia Artists, ICM Artists, Judd Concert Bureau, Allied Arts Association, Alix Williamson, and Friede Rothe, for their professional support and invaluable assistance in arranging interviews with the artists and for responding so graciously to my requests for biographical information, photographs, and other data; to Robert Meissner, Kim Kronenberg, and Beatrice Stein, for their great assistance in contacting artists and procuring information and materials; to the late Harry Zelzer and his wife Sarah, for their generous help on the artist interviews; to Jerry Bush for his fine technical assistance; to Pauline Durack and Margaret Lynch, for their enormous assistance at home taking care of my three sons, Sean, Aaron and Andrew; to the members of my family, for their patient understanding and cooperation despite the inconveniences while this book was in preparation; and finally, to the artists, a very special measure of thanks for their generosity in granting interviews.

Elyse Mach

![]()

CONTENTS

Introduction by Sir Georg Solti

Preface

Claudio Arrau

Vladimir Ashkenazy

Alfred Brendel

John Browning

Alicia de Larrocha

Misha Dichter

Rudolf Firkušný

Glenn Gould

Vladimir Horowitz

Byron Janis

Lili Kraus

Rosalyn Tureck

Andreé Watts

Index

![]()

INTRODUCTION

TO attempt a definition of the nature of a concert pianist is to try to capture the wind. Some were born into a family of music, it is true, but few can boast of the outstanding pianistic abilities of parents or grandparents. Indeed, many overcame the opposition of a family to a musical career. Some began to show a musical preference almost as soon as they could walk; others developed somewhat along the lines of their physical maturity.

But all had something—the talent; it had to be there, because musical talent is something that cannot be learned. Such superb pianists as Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Sauer, Cortot, Backhaus, to name a few—they all had it, and the artists in this book have it. No one can make a pianist like them because the mixture of pianist and musician is a marvelous, almost magical mixture. Anyone who is the least bit musical can learn to play the piano up to a certain point, but at that point progress ceases. The magic that makes the concert pianist or any instrumentalist is not there. For want of a better term, I call it a demon, a devil, a benign devil, but a devil nevertheless. Although a concert may last two hours or more, to the audience it seems like two minutes because they have become mesmerized by the demon that sits at the piano. Not every artist has it to the same degree, but each has enough of it to make him an outstanding pianist.

Given the talent, the prospective artist must have a firm determination to succeed. Some call it stubbornness, others, industriousness, but it’s all the same. To achieve something you believe in is extremely important, especially for the young artist. An artist can always find someone who may not like him personally or agree with him professionally, but he must not allow such attitudes to affect his work or hinder his career. Criticism has to be overcome daily, and a truly good pianist will overcome it. No one can prevent true talent from its rightful destiny. Detours should only serve to make the talent more determined.

It should go without saying that the third ingredient is discipline which is the constant companion of the professional musician; and the virtuoso evolves from that daily practice. Moving the fingers up and down the keyboard becomes for most a daily battle, but one which constantly has to be won. There may have been a few exceptions to the rule, but eventually their absence of discipline caught up with them. The professional pianist can give performances without practicing maybe for a week or two, but usually no longer. As the Polish pianist and statesman, Ignace Paderewski, is known to have once remarked, “If I don’t practice for one day, I know it; if I don’t practice for two days, the critics know it; and if I don’t practice for three days, the audience knows it.”

As one reads Great Pianists Speak for Themselves, it becomes very clear that these keyboard artists did not rely on a miracle or good luck. They are men and women with talent who through industriousness, discipline, and belief in self-achieved stature have become the great pianists of all time. How they reflect upon themselves, their art, and their music should be very interesting indeed, for these are the thoughts of the artists themselves, not what someone else has chosen to write about them.

![]()

PREFACE

THE reluctance of famous people to grant interviews is understandable in the light of the number of misquotes, misinterpretations, and undeveloped generalizations usually attributed to them. Statements assigned notables are not usually distorted intentionally but, when one considers that the personage is questioned as he or she runs for a plane, leaves a stage, or enters a car, half-truths become commonplace.

The artists in this book gave several hours of their time so that they could add depth to their responses, especially in those areas that seemed most important to them. Since the pianists were quite communicative, it was decided to let them speak freely without prompting or interjection from the interviewer. Consequently, the reader will find little interruption in the artists flow of speech. Question-and-answer interviews have their advantage, but they do not often allow the interviewee to develop his or her perceptions. While the danger of writer interpretation is ever present, by presenting the artists’ views as they expand on them, the interviewer avoids putting words into their mouths. It is regrettable that tensions between the Western world and the U.S.S.R. curtailed access to the great pianists of the Soviet Union, and one such interview that was granted had to be withdrawn following recent defections by Soviet artists traveling abroad.

This book is intended for a wide audience because the artists themselves believe that their ideas and viewpoints touch all aspiring musicians, especially pianists, as well as teachers and music audiences. The parent who thinks his child has talent will note the various views on when and how to begin the youngster at the keyboard; the teacher of piano has the opportunity to study the influences of pedagogy, both in quantity and quality, on the student; and, perhaps most important of all, the serious piano student can clearly see what is in store for one who chooses the concert stage as a career.

Lastly, this book is intended for that vast group of aficionados of classical music whose appreciation of artistic skills brings them to the concert halls and to the record shops. How the virtuoso views himself, his art, and his public should satisfy the innate curiosity everyone has about famous individuals. The history of the talent, its development, and fruition will make even the dilettante more appreciative of the artistic accomplishments of these virtuosi.

Elyse Mach

Claudio Arrau

![]()

CLAUDIO ARRAU

Claudio Arrau has made his home in Douglaston, a New York suburb located about thirty-jive miles away, since 1941. Mr. and Mrs. Arrau reside in a white frame house concealed by tall hedges. Mrs. Arrau greeted me at the door and immediately ushered me down a short flight of stairs to the large music room more conspicuous for its walls lined with shelves of books and objets dart than for the black Steinway that occupied its own niche in afar corner of the room.

As Mr. Arrau entered the room, my curiosity about the total artistry of the room almost got the better of me; but as he began to speak I knew that, in his own time, he would explain why a music room was so filled with books, icons, African and pre-Columbian art, antique furniture and oriental rugs. Gentle and mild-mannered, Arrau speaks softly and slowly, delivering his carefully phrased ideas in an animated tone punctuated with much laughter and many gestures. Although he laughs easily, he weighs his words carefully, often stopping to rephrase a thought lest his meaning be misinterpreted. Like most other famous virtuosos, Arrau couldn’t remember wanting to be anything but a concert pianist.

THERE was never a moment of doubt. When I look back, I think I was born playing the piano because, before I realized what I was doing, I was sitting at a piano trying out various sounds and playing in a very natural way. I had a feeling for the instrument. To me, even as a child, the piano seemed to be a continuation of my arms. On the other hand, natural gifts by themselves aren’t enough. They have to be developed, and I was fortunate enough to be aided in my development by Martin Krause, who had studied under Franz Liszt. So I inherited the Liszt tradition, and through Liszt, the Czerny and Beethoven traditions. Krause was the greatest influence in my life because he was my one and only teacher. I may have had the same career without him, but it would have been accomplished much differently.

I know many artists claim they have developed by intuition, but I don’t believe it. Intuition is important, so is talent. But a teacher, a guide who helps you unfold and develop is absolutely necessary. Also, that teacher has to be the right teacher for you, because the teacher-pupil relationship is a two-sided affair involving mutual responses. In a sense I worshiped Krause; I ate up everything he tried to put in front of me. I worked exactly according to his wishes. Krause taught me the value of virtuosity. He believed in that absolutely, but only as a basis for what follows—the meaning of the music, the interpretation of the music. Being a “piano player,” no matter how brilliant, is never enough. I believe in a complete development of general culture, knowledge, intuition, and in a human integration in the Jungian sense of the term. All the elements, all the talents one possesses, should go into the personality as an artist and into the music the artist makes. Concentration should not be on music alone; to better understand music the artist must embrace, as it were, the total universe.

One of the most common criticisms leveled against musicians is that they are so specialized and that they don’t live outside their own realm. The criticism may be valid, and I for one am very much against any attitude or philosophy that gives rise to it. When I teach, for example, I try to awaken not only musical elements in the young artist, but also to inculcate the importance of developing the completely cultured personality—reading, theater, opera, study of art and classical literature, even the study of psychology. All of these contribute enormously to making the complete artist. I myself, though I never went to school, was given the most thorough education. But mostly I continued to educate myself. I never stopped reading and wherever I am, I buy art of all kinds, as you can see. I need to surround myself with beauty. Art, beauty, nature, and knowledge are m...