- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Victorian Decorative Design

About this book

Classic by noted Victorian designer discusses aesthetics, practical considerations of Victorian and Edwardian design. Rich, illuminating treatment of historic styles, beauty, utility, design of furniture, carpets, draperies, textiles, pottery, glass, metalwork, many other elements. Over 180 handsome illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Principles of Victorian Decorative Design by Christopher Dresser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Architektur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I.

DIVISION I.

THERE are many handicrafts in which a knowledge of the true principles of ornamentation is almost essential to success, and there. are few in which a knowledge of decorative laws cannot be utilised. The man who can form a bowl or a vase well is an artist, and so is the man who can make a beautiful chair or table. These are truths; but the converse of these facts is also true; for if a man be not an artist he cannot form an elegant bowl, nor make a beautiful chair.

At the very outset we must recognise the fact that the beautiful has a commercial or money value. We may even say that art can lend to an object a value greater than that of the material of which it consists, even when the object be formed of precious matter, as of rare marbles, scarce woods, or silver or gold.

This being the case, it follows that the workman who can endow his productions with those qualities or beauties which give value to his works, must be more useful to his employer than the man who produces objects devoid of such beauty, and his time must be of higher value than that of his less skilful companion. If a man, who has been born and brought up as a “son of toil,” has that laudable ambition which causes him to seek to rise above his fellows by fairly becoming their superior, I would say to him that 1 know of no means of his so readily doing so, as by his acquainting himself with the laws of beauty, and studying till he learns to perceive the difference between the beautiful and the ugly, the graceful and the deformed, the refined and the coarse. To perceive delicate beauties is not by any means an easy task to those who have not devoted themselves to the consideration of the beautiful for a long period of time, and of this be assured, that what now appears to you to be beautiful, you may shortly regard as less so, and what now fails to attract you, may ultimately become charming to your eye. In your study of the beautiful, do not be led away by the false judgment of ignorant persons who may suppose themselves possessed of good taste. It is common to assume that women have better taste than men, and some women seem to consider themselves the possessors of even authoritative taste from which there can be no appeal. They may be right, only we must be pardoned for not accepting such authority, for should there be any over-estimation of the accuracy of this good taste, serious loss of progress in art-judgment might result.

It may be taken as an invariable truth that knowledge, and knowledge alone, can enable us to form an accurate judgment respecting the beauty or want of beauty of an object, and he who has the greater knowledge of art can judge best of the ornamental qualities of an object. He who would judge rightly of art-works must have knowledge. Let him who would judge of beauty apply himself, then, to earnest study, for thereby he shall have wisdom, and by his wise reasonings he will be led to perceive beauty, and thus have opened to him a new source of pleasure.

Art-knowledge is of value to the individual and to the country at large. To the individual it is riches and wealth, and to the nation it saves impoverishment. Take, for example, clay as a natural material: in the hands of one man this material becomes flower-pots, worth eighteen-pence a “cast” (a number varying from sixty to twelve according to size) ; in the hands of another it becomes a tazza, or a vase, worth five pounds, or perhaps fifty. It is the art which gives the value, and not the material. To the nation it saves impoverishment.

A wise policy induces a country to draw to itself all the we 1th that it can, without parting with more of its natural material than is absolutely necessary. If for every pound of clay that a nation parts with, it can draw to itself that amount of gold which we value at five pounds sterling, it is obviously better thus to part with but little material and yet secure wealth, than it is to part with the material at a low rate either in its native condition, or worked into coarse vessels, thereby rendering a great impoverishment of the native resources of the country necessary in order to its wealth.

Men of the lowest degree of intelligence can dig clay, iron, or copper, or quarry stone ; but these materials, if bearing the impress of mind, are ennobled and rendered valuable, and the more strongly the material is marked with this ennobling impress the more valuable it becomes.

I must qualify my last statement, for there are possible cases in which the impress of mind may degrade rather than exalt, and take from rather than enhance, the value of a material. To ennoble, the mind must be noble; if debased, it can only debase. Let the mind be refined and pure, and the more fully it impresses. itself upon a material, the more lovely does the material become, for thereby it has received the impress of refinement and purity; but if the mind be debased and impure, the more does the matter to which its nature is transmitted become degraded. Let me have a simple mass of clay as a candle-holder rather than the earthen candlestick which only presents such a form as is the natural outgoing of a degraded mind.

There is another reason why the material of which beautiful objects are formed should be of little intrinsic value besides that arising out of a consideration of the exhaustion of the country, and this will lead us to see that it is desirable in all cases to form beautiful objects as far as possible of an inexpensive material. Clay, wood, iron, stone, are materials which may be fashioned into beautiful forms, but beware of silver, and of gold, and of precious stones. The most fragile material often endures for a long period of time, while the almost incorrosible silver and gold rarely escape the ruthless hand of the destroyer. “ Beautiful though gold and silver are, and worthy, even though they were the commonest of things, to be fashioned into the most exquisite devices, their money value makes them a perilous material for works of art. How many of the choicest relics of antiquity are lost to us, because they tempted the thief to steal them, and then to hide his theft by melting them ! How many unique designs in gold and silver have the vicissitudes of war reduced in fierce haste into money-changers’ nuggets ! Where are Benvenuto Cellini’s vases, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s cups, or the silver lamps of Ghirlandajo ? Gone almost as completely as Aaron’s golden pot of manna, of which, for another reason than that which kept St. Paul silent, we cannot now speak particularly.’ Nor is it only because this is a world ‘where thieves break through and steal’ that the fine gold becomes dim and the silver perishes. This, too, is a world where ‘love is strong as death;’ and what has not love—love of family, love of brother, love of child, love of lover—prompted man and woman to do with the costliest things, when they could be exchanged as mere bullion for the lives of those who were beloved?”1 Workmen ! it is fortunate for us that the best vehicles for art are the least costly materials.

Having made these general remarks, I may explain to my readers what I am about to attempt in the little work which I have now commenced. My primary aim will be to bring about refinement of mind in all who may accompany me through my studies, so that they may individually be enabled to judge correctly of the nature of any decorated object, and enjoy its beauties—should it present any —and detect its faults, if such be present. This refinement I shall attempt to bring about by presenting to the mind considerations which it must digest and assimilate, so that its new formations, if I may thus speak, may be of knowledge. We shall carefully consider certain general principles, which are either common to all fine arts or govern the production or arrangement of ornamental forms: then we shall notice the laws which regulate the combination of colours, and the application of colours to objects; after which we shall review our various art-manufactures, and consider art as associated with the manufacturing industries. We shall thus be led to consider furniture, earthenware, table and window glass, wall decorations, carpets, floor cloths, window-hangings, dress fabrics, works in silver and gold, hardware, and whatever is a combination of art and manufacture. I shall address myself, then, to the carpenter, the cabinet-maker, potter, glass-blower, paper-stainer, weaver and dyer, silversmith, blacksmith, gas-finisher, designer, and all who are in any way engaged in the production of art-objects.

But before we commence our regular work, let me say that without laborious study no satisfactory progress can be made. Labour is the means whereby we raise ourselves above our fellows; labour is the means by which we arrive at affluence. Think not that there is a royal road to success—the road is through toil. Deceive not yourself with the idea that you were born a genius—that you were born an artist. If you are endowed with a love for art, remember that it is by labour alone that you can get such knowledge as will enable you to present your art-ideas in a manner acceptable to refined and educated people. Be content, then, to labour. In the case of an individual, success appears to me to depend upon the time which he devotes to the study of that which he desires to master. One man works six hours a day; another works eighteen. One has three days in one; and what is the natural result? Simply this—that the one who works the eighteen hours progresses with three times the rapidity of the one who only works six hours. It is true that individuals differ in mental capacity, but my experience has led me to believe that those who work the hardest almost invariably succeed the best.

While I write, I have in my mind’s eye one or two on whom Nature appeared to have lavishly bestowed art-gifts ; yet these have made but little progress in life. I see, as it were, before me others who were less gifted by Nature, but who industriously persevered in their studies, and were content to labour for success; and these have achieved positions which the natural genius has failed even to approach. Workmen ! I am a worker, and a believer in the efficacy of work.

We will commence our systematic course by observing that good ornament—good decorations of any character, have qualities which appeal to the educated, but are silent to the ignorant, and that these qualities make utterance of interesting facts; but before we can rightly understand what I may term the hidden utterance of ornament, we must inquire into the general revelation which the ornament of any particular people, or of any historic age, makes to us, and also the utterances of individual forms.

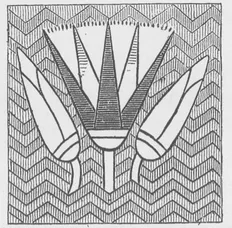

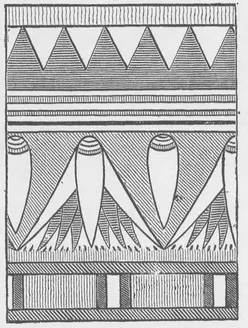

As an illustration of my meaning, let us take the ornament produced by the Egyptians. In order to see this it may be necessary that we visit a museum—say the British Museum—where we search out the mummy-cases ; but as most provincial museums boast one or more mummy-cases, we are almost certain to find in the leading country towns illustrations that will serve our present purpose. On a mummy-case you may find a singular ornament, which is a conventional drawing of the Egyptian lotus, or blue waser-lily2 (see Figs. 1, 2, 3), and in all probability you will find this ornamental device repeated over and over again on the one mummy-case. Notice this peculiarity of the drawing of the lotus—a peculiarity common to Egyptian ornaments—that there is a severity, a rigidity of line, a sort of sternness about it. This rigidity or severity of drawing is a great peculiarity or characteristic of Egyptian drawing. But mark ! with this severity there is always coupled an amount of dignity, and in some cases this dignity is very apparent. Length of line, firmness of drawing, severity of form, and subtlety of curve are the great characteristics of Egyptian ornamentation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

What does all this express ? It expresses the character of the people who created the ornaments. The ornaments of the ancient Egyptians were all ordered by the priesthood, amongst whom the learning of this people was stored. The priests were the dictators to the people not only of religion, but of the forms which their ornaments were to assume. Mark, then, the expression of the severity of character and dignified bearing of the priesthood : in the very drawing of a simple flower we have presented to us the character of the men who brought about its production. But this is only what we are in the constant habit of witnessing. A man of knowledge writes with power and force; while the man of wavering opinions writes timidly and with feebleness. The force of the one character (which character has been made forcible by knowledge) and the weakness of the other is manifested by his written words. So it is with ornaments : power or feebleness of character is manifest by the forms produced.

The Egyptians were a severe people; they were hard task-masters. When a great work had to be performed, a number of slaves were selected for the work, and a portion of food allotted to each, which was to last till the work was completed; and if the work was not finished when the food was consumed, the slaves perished. We do not wonder at the severity of Egyptian drawing. But the Egyptians were a noble people—noble in knowledge of the arts, noble in the erection of vast and massive buildings, noble in the ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- PREFACE.

- Table of Contents

- CHAPTER I.

- CHAPTER II.

- CHAPTER III.

- CHAPTER IV. - DECORATION OF BUILDINGS.

- CHAPTER V.

- CHAPTER VI.

- CHAPTER VII.

- CHAPTER VIII.

- CHAPTER IX.

- CHAPTER X.

- INDEX.

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST