- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lectures in Projective Geometry

About this book

An ideal text for undergraduate courses in projective geometry, this volume begins on familiar ground. It starts by employing the leading methods of projective geometry as an extension of high school-level studies of geometry and algebra, and proceeds to more advanced topics with an axiomatic approach.

An introductory chapter leads to discussions of projective geometry's axiomatic foundations: establishing coordinates in a plane; relations between the basic theorems; higher-dimensional space; and conics. Additional topics include coordinate systems and linear transformations; an abstract consideration of coordinate systems; an analytical treatment of conic sections; coordinates on a conic; pairs of conics; quadric surfaces; and the Jordan canonical form. Numerous figures illuminate the text.

An introductory chapter leads to discussions of projective geometry's axiomatic foundations: establishing coordinates in a plane; relations between the basic theorems; higher-dimensional space; and conics. Additional topics include coordinate systems and linear transformations; an abstract consideration of coordinate systems; an analytical treatment of conic sections; coordinates on a conic; pairs of conics; quadric surfaces; and the Jordan canonical form. Numerous figures illuminate the text.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I

PROJECTIVE GEOMETRY AS AN EXTENSION OF HIGH SCHOOL GEOMETRY

1. Two approaches to projective geometry. There are two ways to study projective geometry : (1) as a continuation of Euclidean geometry as usually taught in high schools, and (2) as an independent discipline, with its own definitions, axioms, theorems, etc. Of these two ways, the first corresponds to the actual historical development of the subject. As Euclidean geometry developed, a large body of theorems having a common character was built up, and theorems having that character (which we will describe more explicitly below) were called projective theorems. But precisely because projective geometry arose from Euclidean geometry, attention began to be directed more and more to the axioms. It was for this reason that the so-called “axiomatic method,” which nowadays is applied in all branches of mathematics, was first applied to projective geometry, from which subject it gradually spread to all the others.

Of the two ways of studying the subject, each has disadvantages. As to the first method, although Euclid may have been definite enough about his axioms, the high schools frequently are not, and as a consequence one is never quite sure what these axioms were. This is also partly the fault of Euclid, and today we can be somewhat more exact than he was. Another disadvantage is that projective geometry consists of theorems of a certain special type, so that Euclid’s axioms, even if made precise, are not entirely suitable.

The axiomatic method of introducing the subject also has disadvantages. For one thing, one has to enter somewhat fully into what is involved in an axiomatic system, and this takes us away from geometry and other fairly familiar things to things that at first sight may seem to be bizarre and to have no bearing on the subject. Besides, the content of an axiomatic system depends on what we want to study: for algebra we would have one system of axioms; for geometry, another; therefore if we really want to come to grips with geometric problems, we have to know, first, roughly what these problems are.

Of the two methods, we will start with the first. Since we do not say precisely what we are assuming, we shall never be able to tell precisely what we are proving. This kind of situation always gives rise to misunderstandings, especially if we insist that we are actually proving things. The first chapter will therefore not be directed toward establishing theorems with complete rigor, but toward supplying background material that will be helpful in the axiomatic method part of the book. At the same time, although we will not insist upon complete rigor, neither will we allow ourselves to make obvious mistakes in logic.

FIG. 1.1

FIG. 1.2

2. An initial question. The question toward which projective geometry first directed itself was, “How do we see things?” or “What is the relation between a thing itself, say a figure, and the thing seen?” More particularly, “Do we ever see a thing exactly as it is? “ Take this rectangular table: we know it is rectangular. But a little thought shows us that we do not see it as rectangular. In fact, a little lack of thought will also show this. For suppose we try to draw the table. We draw a rectangle (Fig. 1.1). This is the top of the table. But now we try to put the legs on, and we see that we cannot. To do so, we have to draw the rectangle in a nonrectangular shape; then we can put the legs on (Fig. 1.2).

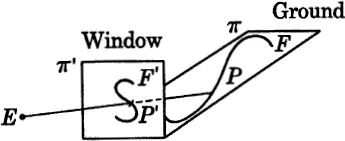

FIG. 1.3

This argument will certainly convince us that angles are not always what they seem. Let us try, however, to make the argument more precise. For the following, we assume only one eye.

Let us suppose we are looking through the window onto the ground (which may be sloping), as illustrated in Fig. 1.3. On the ground is a figure, say a large letter S. The way we see this letter is by light passing from the points of S and entering the eye. We therefore have to consider lines joining the point E, representing the eye, to the various points of the figure S. These lines cut the windowpane in various points. If P is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Chapter I. Projective Geometry as an Extension of High School Geometry

- Chapter II. The Axiomatic Foundation

- Chapter III. Establishing Coordinates in a Plane

- Chapter IV. Relations Between the Basic Theorems

- Chapter V. Axiomatic Introduction of Higher-Dimensional Space

- Chapter VI. Conics

- Chapter VII. Higher-Dimensional Spaces Resumed

- Chapter VIII. Coordinate Systems and Linear Transformations

- Chapter IX. Coordinate Systems Abstractly Considered

- Chapter X. Conic Sections Analytically Treated

- Chapter XI. Coordinates on a Conic

- Chapter XII. Pairs of Conics

- Chapter XIII. Quadric Surfaces

- Chapter XIV. The Jordan Canonical Form

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lectures in Projective Geometry by A. Seidenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mathematics & Geometry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.