- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Considerable research has been devoted to the formulation and solution of problems involving flow within connected networks. Independent of these surveys, an extensive body of knowledge has accumulated on the subject of queues, particularly in regard to stochastic flow through single-node servicing facilities. This text combines studies of connected networks with those of stochastic flow, providing a basis for understanding the general behavior and operation of communication networks in realistic situations.

Author Leonard Kleinrock of the Computer Science Department at UCLA created the basic principle of packet switching, the technology underpinning the Internet. In this text, he develops a queuing theory model of communications nets. Its networks are channel-capacity limited; consequently, the measure of performance is taken to be the average delay encountered by a message in passing through the net. Topics include questions pertaining to optimal channel capacity assignment, effect of priority and other queue disciplines, choice of routine procedure, fixed-cost restraint, and design of topological structures. Many separate facets are brought into focus in the concluding discussion of the simulation of communication nets, and six appendices offer valuable supplementary information.

Author Leonard Kleinrock of the Computer Science Department at UCLA created the basic principle of packet switching, the technology underpinning the Internet. In this text, he develops a queuing theory model of communications nets. Its networks are channel-capacity limited; consequently, the measure of performance is taken to be the average delay encountered by a message in passing through the net. Topics include questions pertaining to optimal channel capacity assignment, effect of priority and other queue disciplines, choice of routine procedure, fixed-cost restraint, and design of topological structures. Many separate facets are brought into focus in the concluding discussion of the simulation of communication nets, and six appendices offer valuable supplementary information.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

chapter 1

Introduction

We regularly encounter situations involving flow in our daily living. Consider, for example, the movement of automobile traffic, the transfer of goods, the streaming of water, the transmission of telephone or telegraph messages, and the passage of customers through the checkout counter of a supermarket. Although these examples represent rather distinct functional systems, they possess a fundamental property in common: they represent processes involving the flow of some commodity through a channel or a network of channels.

1.1Systems of Flow: Examples

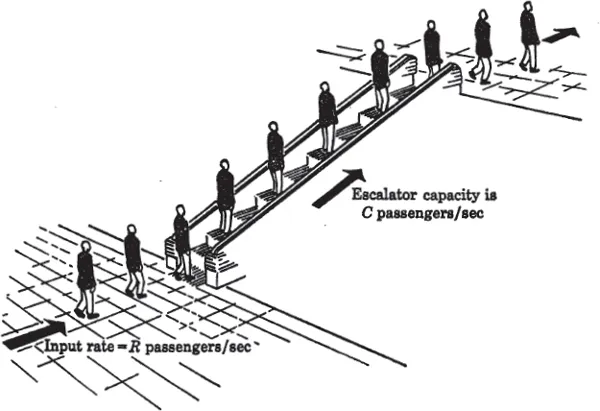

Let us begin by discussing some examples which illustrate the significant properties of various systems of flow. The simplest structural system consists of a single channel. The flow through that channel is made up of a pattern of arrivals (of some commodity), each of which comes up to the channel and requires or demands the use of that channel for a certain interval of time. It becomes immediately obvious that if we are to satisfy the demands placed on the system, we must ensure that the capacity of our channel is sufficient to handle the average rate of flow. If we have a steady flow,1 then the problem is straightforward. For example, consider a department-store escalator which can accept a steady input of up to C passengers per second, as shown in Fig. 1.1. If the rate R at which customers arrive at the escalator is constant (i.e., a steady flow), then either R ≤ C, in which case no waiting lines build up and the steady flow is sustained, or else R > C, in which case the waiting line grows without bound and the system overflows.

Thus, steady flow through a single-channel system is easily disposed of. On the other hand, the case of fluctuating or unsteady flow through a single channel is a problem of considerable complexity. We illustrate this unsteady flow with a second example. Consider the familiar situation of a bakery store with one clerk at which customers arrive at unpredictable times. Before a customer is served, it is generally not clear exactly how long he will engage the clerk, and so his demand (or service time) on the channel (the clerk) is unpredictable. Owing to this uncertain or unsteady flow, we may expect a waiting line of customers to form in the bakery. We may assume, as is usually the case, that each customer receives a numbered ticket upon entering the store, so that a first-come first-served priority is maintained. Now, even if the clerk is able to keep up with the average demand of the customers, a waiting line will often form. Why this is so may easily be appreciated, for two customers entering the empty store, one directly following the other, immediately give rise to a waiting line of one customer. Thus, waiting lines form, in general, when a higher than average flow occurs and overloads the clerk; on the other hand, when the flow is smaller than average, the clerk may find herself idle for some period. In any form of flow, whenever the average input rate exceeds the channel capacity, the waiting line grows without bound.

Fig. 1.1. Department-store escalator problem—an example of steady flow through a single channel.

Fig. 1.2. Diaper-transport problem, showing channel capacity.

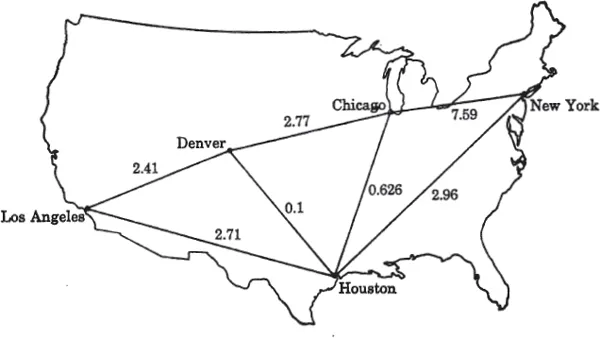

We now move ahead to the more involved case of a network of channels. Once again, we begin by considering steady flow. A simple example of such a net is shown in Fig. 1.2 and may be referred to as the diaper-transport problem. The diaper manufacturer in New York is faced with the problem of establishing a steady flow of newly produced diapers to his outlet in Los Angeles. The diapers may travel only along the routes shown in the figure. The number on each path indicates the maximum diaper tonnage that may pass along that path each week. Assuming that Los Angeles is in constant dire need of as many diapers as can be shipped, we wish to find the transport schedule which maximizes the steady flow from New York to Los Angeles. Problems of this general type have been carefully analyzed, and computationally efficient solution procedures exist [l].2 Our immediate purpose in presenting this example is to convey the notion of a steady flow in a connected network of channels.

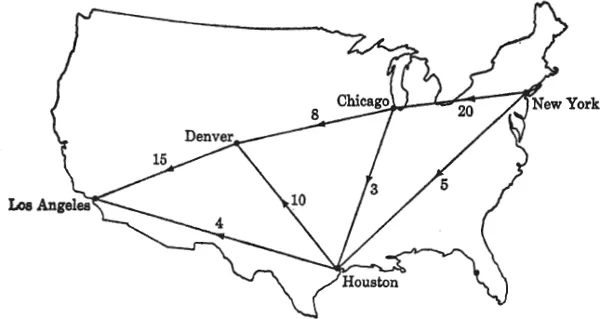

Let us now take the final step in our development and consider an example of unsteady flow in a connected network. We choose as an example a communication net whose topology (structure) is identical with the diaper-transport problem, but whose operation is significantly different. The function of this net is to transmit telegraph messages between the cities shown in Fig. 1.3.

Fig. 1.3. United States telegraph-network example.

For graphical simplicity, each branch in this example represents a two-way connection (or channel) between cities, each with a capacity in binary digits (bits) per second equal to the number shown in the figure. We recognize that the times of arrival of new telegrams at the various cities are, in general, unpredictable, as is the length of any particular telegram; consequently, we expect a waiting line of messages to form at each of the cities. This is not unlike the situation in our bakery-store example. Moreover, we are not certain as to where the next telegram will originate or what its destination will be. Finally, we are faced with the additional complication that telegrams in transit may pass through intermediate relay cities, where they must be received, stored, and then retransmitted.

A man sending a telegram from New York to Los Angeles may wish to know how long the transmission is expected to take. A large national airline may be interested in installing a private telegraph communication net; they would like to know how much capacity will be required on each channel so as to provide an acceptable average delay for a given traffic density. We propose to answer these and other questions in succeeding chapters.

1.2A Closer Look

Up to this point, we have given heuristic descriptions of some flow problems and have found that important differences exist among them. As a result, it is necessary for our purposes to classify all systems of flow into four distinct groups: steady flow through a single channel, unsteady flow through a single channel, steady flow through a network of channels, and unsteady flow through a network of channels.

Let us return to our four examples again and examine more carefully the class of problems from which each is drawn. The departmentstore escalator example is representative of single-channel systems subject to steady flow inputs. The solution of these systems is, as we have seen, trivial, and in fact they represent a special case of the more general class of single-channel systems subject to unsteady flow. Therefore, we pass immediately to this second class of single-channel systems, which we have illustrated with our bakery-store example. As indicated, this problem is hardly trivial. Indeed, a substantial theory of waiting-line (or queueing) processes exists which deals with the description and analysis of the effects of unsteady (or stochastic) flow. By stochastic flow we mean specifically that both the time between successive arrivals to the system and the demand placed on the channel by each of these arrivals are random quantities. We recognize that the special case of a stochastic flow in which the interarrival times are all equal and in which the service demands of each customer are the same reduces to our original steady-flow problem. That is, steady flow is a special case of stochastic flow. However, as opposed to steady flow, a queue may form during stochastic flow even if the average flow rate does not exceed the capacity of the channel; in such a case, the average queue length remains finite. In Appendix A we derive some of the results of queueing theory which we shall use in our analysis of communication nets. We suggest a careful reading of this appendix to the reader unfamiliar with queueing theory.

One of the earliest investigations of a queueing process dates back to 1907, when E. Johannsen3 published two papers concerning delays and busy signals in telephone traffic problems. Under his influence, A. K. Erlang4 undertook the consideration of similar problems, and an English translation and summary of Erlang’s major contributions may be found in [2]. A number of others also contributed to the early development of queueing theory [3,4,5,6]. In 1928, T. C. Fry [7] published his book (which has since become a classic work) surveying and unifying the approach to congestion problems up to that time. In 1939, Feller [8] made an outstanding contribution to queueing theory through his presentation of the birth and death process.

In the early 1950s, it became obvious that many of the results obtained in the field of telephony were applicable to more general situations; thus started investigations into waiting lines of many kinds which have developed into modern queueing theory (a theory which finds numerous applications in the field of operations research). The emphasis has been on single-channel facilities, i.e., systems in which “customers” enter, join a queue, eventually obtain “service,” and upon completion of this service leave the system, as in our bakery-store example. D. G. Kendall published two notable papers [9, 1951, and 10, 1953] in which he made substantial contributions to the theory. In 1952, D. V. Lindley [11] derived an integral equation describing queueing processes with arbitrary arrival and service distributions. A number of other researchers have ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Preface to the 2007 Dover Edition

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Summary of Results

- 3. The Problems of an Exact Mathematical Solution to the General Communication Net

- 4. Some New Results For Multiplechannel Systems

- 5. Waiting Times for Certain Queue Disciplines

- 6. Random Routing Procedures

- 7. Simulation Of Communication Nets

- 8. Conclusion

- A. A Review of Simple Queueing Systems

- B. Theorems and Proofs for Chapter 4

- C. Theorems and Proofs for Chapter 5

- D. Theorems and Proofs for Chapter 6

- E. An Operational Description of the Simulation Program

- F. Alternate Routing Theorems and Their Proofs

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Communication Nets by Leonard Kleinrock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.