![]()

Chapter 1

The Wave Nature of X Rays

Scarcely any other invention in history was exploited as promptly as were x rays. Within a few months of their discovery by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, they were being used for medical diagnostic purposes and for the examination of metal castings. Yet it was not until nearly twenty years later that their true nature was established.

The question of the nature of x rays had been widely argued almost from the start. Many scientific observers, as well as a large part of the general public, appeared to regard them as identical to cathode rays, the beams of electrons emitted from the cathode of an electrical discharge in a low-pressure gas, despite the fact that they were unaffected by magnetic fields. Other scientists thought that they were longitudinal vibrations in the “aether”; still others suspected that they were transverse waves of a character similar to light. The difficulty lay in the fact that the known properties and producible effects did not seem to fit any of these hypotheses. When the rays struck matter, they were scattered, much as light is scattered from a cloudy liquid. But they could not be refracted or reflected.1 Efforts to produce polarization by selective absorption, in the manner used for visible light in tourmaline, were also unsuccessful. Charles Barkla, in 1906, demonstrated polarization by double scattering,2 but many people were not convinced, since such experiments could also be explained in terms of spinning particles. The real touchstone of the wave nature, as Thomas Young had recognized in regard to visible light a century earlier, was the production of interference effects. Attempts in this direction were hampered by a lack of knowledge of the wavelength range. The decisive work was done in 1912 by Max von Laue, Walter Friedrich, and Paul Knipping, and earned a Nobel prize in physics for Laue in 1914. This chapter describes their work, as originally presented to the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences and published in its Meeting Reports, and subsequently republished in Annalen der Physih.

Actually, previous efforts to detect interference had been made. As early as 1899, Hermann Haga and Cornelis Wind had passed a beam of x rays through a triangular aperture. If the x rays were waves, they should have been diffracted by the edges of the slit, and the image on a photographic plate some distance behind the slit should have been broader than the slit itself3; the amount of broadening, together with the dimensions of the apparatus, would then give an estimate of the wavelength. Haga and Wind concluded that if there were interference effects, the wavelengths involved must be less than about 10-9 cm. This work was repeated by Bernhard Walter and Robert Pohl in 1908, with even more discouraging results—they put limits of the order of 10-10 cm on the wavelength. Their work, however, was reanalyzed in 1912 by Arnold Sommerfeld, with the help of photometric measurements on the original photoplates by Peter Koch, and the conclusion of Haga and Wind was supported: No assurance could be found that waves were actually involved, but if they were, they must have wavelengths of the order of 10-9 cm.

What Laue did was to fit this piece of data with others from the theory of solids and atomic theory. He knew, first, that “already in 1850 there was introduced into crystallography by Bravais the theory that the atoms in crystals are arranged in a spatial lattice. If the Röntgen rays truly consist of electromagnetic waves, then it is to be expected that on excitation of the atoms to vibrations, free or forced, the space-lattice structure will give rise to interference phenomena.” Moreover, “the constants of this lattice can be easily calculated from the molecular weight of the crystallized compound, its density, and the number of molecules per gram molecule, in addition to the crystallographic data. One finds for them just the order of magnitude 10-8 cm....” This was just what was needed to produce significant interference phenomena with x rays, if indeed the rays were wavelike in character.

The known results of optical interference theory could not be taken over directly, because of the “considerable complication ... that for the space lattice a threefold periodicity is present, whereas for optical gratings one has a periodic repetition only in one direction, or ... at most two directions.” Laue, therefore, worked out the theory on the basis that each atom was excited an equal amount by the influence of an incident plane wave traveling at the speed of light. The details of this derivation are of no concern here; the crucial result was a set of three equations for the direction in which the scattered intensity would have a maximum. Each of these equations “represents a set of circular cones whose axes coincide with one of the edges” of the elementary unit of the space lattice. “Now, obviously, only in exceptional cases will it happen that one direction satisfies all three conditions at the same time.... Nevertheless, a visible maximum of intensity is to be expected when the line of intersection of two cones of the first two sets lies close to a cone of the third set.” If the scattered rays strike plane photographic plates, these maxima will produce isolated spots, which, however, should be grouped along families of conic sections4—more particularly, at points where three curves, one from each of three families, intersect or nearly intersect.

“It must be observed that for a given space lattice the division into elementary parallelepipeds is not unique, but can be carried out in innumerable ways.... According to the foregoing, the intensity maxima must be able to be grouped along interrupted conic sections around ... axes [arising from such alternative divisions], as in general, to each such kind of division belongs a way of grouping the maxima.”

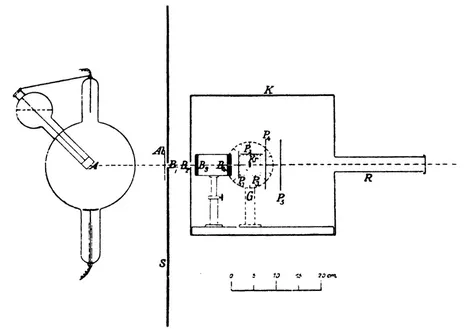

At Laue’s suggestion, Friedrich and Knipping carried out the experimental test. “After some preliminary studies with a provisional apparatus,” the apparatus shown in Fig. 1-1 was built. “From the Röntgen rays proceeding from the anticathode A of a Röntgen tube, a small pencil of about 1 mm diameter was cut off by the stops B1 to B4. This pencil penetrates the crystal Kr, which is set up on a goniometer G. Around the crystal, in various directions and at different distances, were fixed photographic plates P, on which was recorded the intensity distribution of the secondary radiation emanating from the crystal. The setup was guarded against unwanted radiation in a satisfactory way by a large lead shield S as well as by the lead case K.

“The arrangement of the entire experimental setup was effected by optical means. We had a cathetometer, whose telescope was fitted with a crosshair, set up immovably. The ‘hot spot’ of the anticathode, the stops, and the goniometer axis were brought in turn into the optical axis of the telescope.... The stops B1 to B3 mainly blocked off the secondary radiation from the tube walls, while stop B4 formed the limits for the pencil of Röntgen rays incident on the crystal. This ordinarily had a diameter 0.75 mm, was drilled in a lead disk 10 mm thick, and could be adjusted by means of three positioning screws (not shown) in such a way that the axis of the hole coincided exactly with the axis of the telescope or the axis of the pencil of rays. In this way it was arranged that a ray pencil of circular cross section fell on the crystal.... The tube R served ... to avoid as much as possible the secondary rays that were produced by the primary radiation striking the rear wall of the case.

Fig. 1-1. Friedrich and Knipping’s apparatus for studying the scattering of x rays penetrating a crystal. [Ann. Physik 41 (1912), p. 979, Fig. 1.]

“After this adjustment, ... the axis of the goniometer was set perpendicular to the path of the rays in the usual way. In the same way the different plate holders were ... adjusted.... When the apparatus was oriented to that extent, the crystal to be irradiated, which was fastened to the goniometer table by a trace of sticky wax, was put in place, this again with the help of the telescope already mentioned.... This ... very essential adjustment we could make to within a precision of a minute [of arc].”

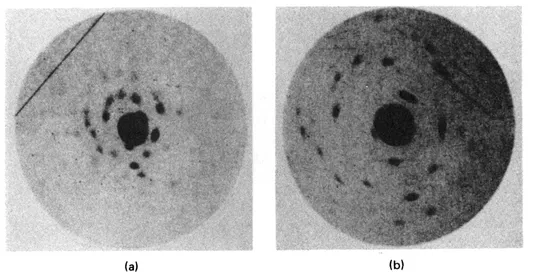

The first exposure with the final apparatus used a “middling” crystal of copper sulfate that had been used in the preliminary studies. The figures obtained on plates P4 and P5 in this exposure are shown in Fig. 1-2. “It is noteworthy that the distances (crystal—P4) and (crystal—P5) are in proportion to the sizes of the figures on P4 and P5, respectively, from which it is established that the rays travel out from the crystal in straight lines. It is further to be observed that the sizes of the individual secondary spots, despite the greater distance of plate P5 from the crystal, remain the same. This is taken as a sure indication that the secondary rays producing each individual spot leave the crystal as a parallel beam.

Fig. 1-2. Two figures obtained in the first exposure: (a) from plate P4 of Fig. 1-1, (b) from plate P5. [Ann. Physik 41 (1912), Plate I, Figs. 2 and 1, respectively.]

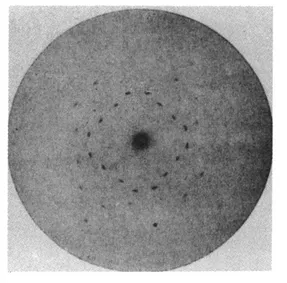

“It is to be expected that the phenomenon will be more transparent and easy to understand with a crystal of the regular [i.e., cubic] system than with the triclinic copper sulfate, since it can be assumed5 with certainty that the pertinent space lattice is of the greatest possible simplicity. Regular zinc blende seemed suitable to us.... We had a plane parallel plate of 10 X 10 mm dimensions and 0.5 mm thick cut ... parallel to a cube face (perpendicular to a crystallographic principal axis) from a good crystal. This plate was oriented ... so that the primary rays penetrated the crystal perpendicular to the cube face. Figure [1-3] shows the result of one such trial. The pattern of the secondary spots is completely symmetric around the position of the unscattered beam.... [The fourfold nature of the symmetry] is certainly one of the most beautiful pieces of evidence for the space lattice of the crystal, and that no property other than the space lattice alone comes into play here.”

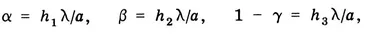

A slightly later paper by Laue contained a more detailed analysis. Laue had, as noted earlier, already derived the equations for the directions of the maxima. For the case of a cubic crystal with the incident beam directed along one of the principal axes, they take the simple form

where λ is the wavelength; α is the length of one edge of the elementary cubic unit of the crystal lattice; α, β, and γ are the cosines of the angles between the direction of the maximum and the x, y, and z axes, respectively (the z axis being the direction of the incident beam); and h1, h2, and h3 are integers (positive, negative, or zero). He was able to account for all the points in Fig. 1-3 by suitable choices of the three h’s and the assumption that the radiation consisted of five discrete wavelengths.

Fig. 1-3. The pattern of spots produced by x rays after passing through a crystal of zinc sulfide. [Ann. Physik 41 (1912), Plate II, Fig. 5.]

Laue’s analysis was soon subjected to criticism by W. L. Bragg, who noted that there were several sets of h’s which would satisfy the ...