![]()

PART I

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

![]()

I. Playing with fingers

LET us begin at the beginning. I am not writing a history of mathematics; this could be done only on the basis of written evidence, and how far from the beginning is the first written evidence! We must imagine primitive man in his primitive surroundings, as he begins to count. In these imaginings, the little primitive man, who grows into an educated human being before our eyes, will always come to our aid; the little baby, who is getting to know his own body and the world, is playing with his tiny fingers. It is possible that the words ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’ and ‘four’ are mere abbreviations for ‘this little piggie went to market’, ‘this little piggie stayed at home’, ‘this one had roast beef’, ‘this one had none’ and so on; and this is not even meant to be a joke: I heard from a medical man that there are people suffering from certain brain injuries who cannot tell one finger from another, and with such an injury the ability to count invariably disappears. This connexion, although unconscious, is therefore still extremely close even in educated persons. I am inclined to believe that one of the origins of mathematics is man’s playful nature, and for this reason mathematics is not only a Science, but to at least the same extent also an Art.

We imagine that counting was already a purposeful activity in the beginning. Perhaps primitive man wanted to keep track of his property by counting how many skins he had. But it is also conceivable that counting was some kind of magic rite, since even today compulsion-neurotics use counting as a magic prescription by means of which they regulate certain forbidden thoughts; for example, they must count from one to twenty and only then can they think of something else. However this may be, whether it concerns animal skins or successive time-intervals, counting always means that we go beyond what is there by one: we can even go beyond our ten fingers and so emerges man’s first magnificent mathematical creation, the infinite sequence of numbers,

the sequence of natural numbers. It is infinite, because after any number, however large, you can always count one more. This creation required a highly developed ability for abstraction, since these numbers are mere shadows of reality. For example, 3 here does not mean 3 fingers, 3 apples or 3 heartbeats, etc., but something which is common to all these, something that has been abstracted from them, namely their number. The very large numbers were not even abstracted from reality, since no one has ever seen a billion apples, nobody has ever counted a billion heartbeats; we imagine these numbers on the analogy of the small numbers which do have a basis of reality: in imagination one could go on and on, counting beyond any so-far known number.

Man is never tired of counting. If nothing else, the joy of repetition carries him along. Poets are well aware of this; the repeated return to the same rhythm, to the same sound pattern. This is a very live business; small children do not get bored with the same game; the fossilized grown-up will soon find it a nuisance to keep on throwing the ball, while the child would go on throwing it again and again.

We go as far as 4? Let us count one more, then one more, then one more! Where have we got to? To 7, the same number that we should have got to if we had straight away counted 3 more. We have discovered addition

4 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 4 + 3 = 7

Now let us play about further with this operation: let us add to 3 another 3, then another 3, then another 3! Here we have added 3’s four times, which we can state briefly as: four threes are twelve, or in symbols:

3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 4 x 3 = 12

and this is multiplication.

We may so enjoy this game of repetition that it might seem difficult to stop. We can play with multiplication in the same way: let us multiply 4 by 4 and again by 4, then we shall get

This repetition or ‘iteration’ of multiplication is called raising to a power. We say that 4 is the base, and we indicate by means of a small number written at the top right-hand corner of the 4 the number of 4’s that we have to multiply; i.e. the notation is this:

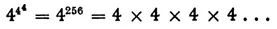

As is easily seen, we keep getting larger and larger numbers: 4 x 3 is more than 4 + 3, and 43 is a good deal more than 4 x 3. This playful repetition carries us well up amongst the large numbers; even more so, if we iterate raising to a power itself. Let us raise 4 to the power which is the fourth power of four:

44 = 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 = 64 x 4 = 256

and we have to raise 4 to this power:

I have no patience to write any more, since I should have to put down 256 4’s, not to mention the actual carrying out of the multiplication! The result would be an unimaginably large number, so that we use our common sense, and, however amusing it would be to iterate again and again, we do not include the iteration of powers among our accepted operations.

Perhaps the truth of the matter is this: the human spirit is willing to play any kind of game that comes to hand, but only those of these mathematical games become permanent features that common sense decides are going to be useful.

Addition, multiplication and raising to powers have proved very useful in man’s common-sense activities and so they have gained permanent civil rights in mathematics. We have determined all those of their properties which make calculations easier; for example, it is a great saving that 7 X 28 can be calculated not only by adding 28 7 times, but also by splitting it into two multiplication processes: 7 X 20 as well as 7 X 8 can quite easily be calculated and then it is readily determined how much 140 + 56 will be. Also in adding long columns of numbers how useful it is to know that no amount of rearranging of the order of the additions is going to spoil the result, as for example 8 + 7 + 2 can be carried out as 8 + 2 = 10 and to 10 it is quite easy to add 7; in this way I have cunningly avoided the awkward addition 8 + 7. We merely have to consider that addition really means counting on by just as much as the numbers to be added and then it becomes clear that changing the order does not alter the result. To be convinced of the same thing about multiplication is a little harder, since 4 x 3 means 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 and 3 x 4 means 4 + 4 + 4 and it is really not obvious that

3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 4 + 4 + 4

But this straightaway becomes clear if we do a little drawing. Let us draw four times three dots in these positions . . . one underneath the other

Everyone can see that this is the same thing as if we had drawn three times four dots in the following positions

next to each other. In this way 4 x 3 = 3 x 4. This is why mathematicians have a common name for the multiplier and the multiplicand; the factors.

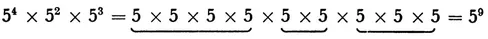

Let us look at one of the rules for raising to powers:

If we get tired of all this multiplying, we can have a little rest; the product of the first three 4’s is 43, there is still 42 left, so

The exponent of the result is 5, which is 3 + 2; so we can multiply the two powers of 4 by adding their exponents. As a matter of fact this is always so. For example:

here again 9 = 4 + 2 + 3.

Let us recapitulate the ground we have covered: it was counting that led to the four rules. It could be objected, where does subtraction come in all this? And division? But these are merely reversals of the operations we have had so far (as are extraction of roots and logarithms). Because, for example, 20 ÷ 5 involves our knowing the result of a multiplication sum, namely 20, we are seeking the number which if multiplied by 5 gives 20 as the result. In this case we succeed in finding such a number, since 5 x 4 = 20. But it is not always easy to find such numbers; in fact it is not even cer...