- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Medieval Village

About this book

Renowned medievalist offers exceptionally detailed, comprehensive and vivid picture of medieval peasant life, including nature of serfdom, manorial customs, village discipline, peasant revolts, the Black Death, justice, tithing, games and dance, much more. Much on exploitation of peasant classes. "...a remarkable book..." — Times (London) Literary Supplement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Medieval Village by G. G. Coulton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia europea medieval. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

THE OPEN ROAD

NEARLY forty years ago, when teaching in South Wales, I often spent the summer half-holidays between noon and midnight in tracking some small tributary of the Towy to its source in the mountains ; and this led me by devious ways through many solitary fields. Over and over again, when the slanting shadows were beginning to show that beautiful countryside in its most beautiful aspect—when those words of Browning’s Pompilia came most inevitably home: “for never, to my mind, was evening yet but was far beautifuller than its day ”—over and over again, at these moments, I found myself hailed by some lonely labourer, or by one of some small group, leaning on his hoe and crying to me across the field. It was always the same question: “What’s the time of day?”—the question implicit in that verse of Job: “As a servant earnestly desireth the shadow, and as an hireling looketh for the reward of his work.” The sunlight was not long enough for me on my half-holiday; it was too long for these labouring men; and the memory of those moments has often given deeper reality to that other biblical word:

Behold, the hire of the labourers who have reaped down your fields, which is of you kept back by fraud, crieth: and the cries of them which have reaped are entered into the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth. . . . Behold, the husbandman waiteth for the precious fruit of the earth, and hath long patience for it, until he receive the early and latter rain. Be ye also patient; stablish your hearts: for the coming of the Lord draweth nigh.

No man who is concerned for the future of human society can neglect the peasant; and there is much to be said for beginning with the peasant. In him we see elementary humanity; he appeals to our deepest sympathies; we may profitably imitate his patience; his struggles may move us to that “ large and liberal discontent” of which William Watson speaks, and which is the beginning of all progress in this world. And yet, the more we study him, the more we come back to that lesson of patience; for he makes us realize the great gulf that is fixed between ignorant innocence and self-controlled innocence; between the cloistered and fugitive virtue of those who are cut off from conspicuous sins, and the tried virtue of those who, amid great wealth, avoid self-indulgence, or who, wielding great power, use it rather for other men’s good than for their own. During many years, the social history of the Middle Ages had made me distrust current encomiums on the Russian or the Chinese peasantry as ideal societies, and as models for our own imitation. No doubt there was once such a time in Russia, and perhaps there is still in China—a time of happy equilibrium, at which the peasant has for the moment all that he needs, and strives as yet for no more. The fifteenth century marked a time of comparative prosperity and rest for the peasantry of England and Flanders and parts of Germany. But this is a world in which things must move, sooner or later; and all movement implies friction; and the worst friction is apt to come after long periods of static peace. Under stagnant order lies always potential disorder. The peasant is often quiet only because he ignores the lessons which are learned amid more rapid social currents. We must understand the peasant; but we must understand both sides of him; if chance debars him from the rôle of Hampden and Milton, it is the same chance which forbids his wading through slaughter to a throne.

From the first, however, I must disclaim any special knowledge of two very important branches of my subject; for I have never specialized either in constitutional history or in political economy. Even with regard to our own day, my knowledge is mainly confined to what I have picked up casually from the newspapers and from ordinary books and conversation; and so also it is with the past. My impressions on those points, therefore, will be only those of a miscellaneous reader; I must try to describe things as they were seen and felt not so much by the political philosopher of the Middle Ages, as by the medieval man in the street. We have had rather too much, I think, of formal political philosophy in pre-Reformation history, and not quite enough of those miscellaneous facts, those occasional cross-lights from multitudinous angles, which help us so much to realize (in F. W. Maitland’s words) our ancestors’ common thoughts about common things. In a very real sense, therefore, this essay is that of a man thinking aloud on the theme first suggested by the Vale of Towy.

In the course of the years that have elapsed since those days, wandering up and down in the Middle Ages, I have constantly come across the medieval peasant, and especially the serf on monastic estates. He hails me, as of old, across the field, across the slanting sunlight, across a land that seems more beautiful as the shadows lengthen, and the glare softens into afterglow, and death lends a deeper meaning to life. “Another race hath been, and other palms are won”; but there is only slow and gradual change in the human heart; human problems remain fundamentally very much the same; the peasant who, six hundred years ago, would have cried: “ Come over and help us,” cries now across those centuries: “ Go over and help my fellows.” Therefore, though I am more conscious of ignorance than of familiarity ; though there is a gulf in life and thought between me and even the modern peasant; though I could no more undertake to specify all the medieval serf’s legal disabilities and abilities at law than I would undertake to act as legal adviser to his descendant of today who might be litigating with his landlord, yet I have struggled to get into closer touch with him; and it is in that spirit that I invite my readers to come with me.

We must not be afraid of ghosts or of strange fellow-travellers, nor impatient of church bells and incense; for this is a province of the île Sonnante. For good or for evil, medieval society was penetrated with religious ideas, whether by way of assent or of dissent; and medieval state law not only usually admitted the validity of church law, but often undertook to enforce church law with the help of the secular arm. It may have been absurd that the medieval socialist or communist should plead as his strongest argument a highly legendary story of Adam and Eve, and that, on the other hand, the medieval conservative should clinch the whole question with a single sentence ascribed to an illiterate Jewish fisherman; it is possible to treat this as a mere absurdity, but it is not possible to ignore it altogether without deceiving both ourselves and our readers on a point which lies at the root of all medieval history. Therefore medievalists are forced, in a sense, to write church history, and are thus exposed to all the temptations of the ecclesiastical historian. But the first step towards overcoming these besetting temptations is frankly to recognize them. When we realize that here is a subject on which every man must be more or less prejudiced (unless he be trying to get through life without any even approximately clear working theory of life in his head), then we can attach far less importance to a man’s prejudices, which are more or less inevitable, than to his attempts at disguise, which are unnecessary.

We cannot fully understand the social problems of our own day without realizing how those problems presented themselves to our forefathers, and by what ways they were approached, and with what measure of success or failure. And this, again, we cannot understand without traversing ground that smoulders still with hidden fires, political or religious. But it depends only on ourselves that such a journey should diminish rather than increase our prejudices. We do indeed enter upon it with certain ideas of our own; we may quit it with even stronger convictions in the same direction, yet with more sympathy, at bottom, for the best among those who differ from us. The only real enemy which either side has to fear is mental or literary dishonesty; since this is even more formidable as a domestic than as a public foe. The greatest men of past centuries are those who, by their example, entreat us to judge their own words and actions with the most unsparing exactitude, for the guidance of all present and future efforts towards social progress. To study medieval society without thinking of present-day and future society seems to me not only impossible in fact, but even unworthy as an ideal. While we strive to see the peasant of the past as he would have appeared to open-minded observers in his own day, we must at the same time appreciate and criticize him from the wider standpoint of our later age. Aquinas and Bacon, if they had known things which the modern schoolboy knows, would have seen their contemporaries not only as they were but as they might be; therefore, if we strive to eliminate from our own minds the intellectual and moral gains of these six centuries, we gain nothing in historical focus by this limitation; we gain nothing in clearness of definition; we simply exchange our telescope for a pair of blinkers.

If this be true, then, to the modern student of village life, the main question at bottom, if not on the surface, must be a question of criticism and comparison. Were men happy six hundred years ago—happy in the full human sense, and not merely with the acquiescence of domestic animals—under conditions which would render the modern villager unhappy? And, in so far as this may be so, is it not rather deplorable? since there are certain factors of life without which no man ought to be content. Therefore the main line of enquiry, after all, is fairly simple. The documentary records of rural life in the Middle Ages are abundant. Let us face the facts which these reveal; and then, putting ourselves into the position of Plato’s Er the Armenian, with one chart before us showing past conditions of existence and another showing corresponding life in our own day, let us consider which we should seriously choose.

For, in speaking of our own day, we must say “corresponding life,” and not circumscribe our choice by using in both cases this word peasant. In Chaucer’s day, probably at least 75 per cent. of the population of these islands were peasants; and, out of every hundred men we might have met, more than fifty were unfree. Therefore the analogues of Chaucer’s peasants constitute three-quarters of modern society—not only our present country labourers, but a large proportion of our own wage-earning population, and even some of our professional classes, from the unskilled worker to the skilled mechanic, the clerk, the struggling tradesman, doctor, or lawyer. The writer and the reader of this present volume might easily have been born in actual serfdom five hundred years ago; the chances are more than even on that side; and which of us will feel confident that he would have fought his way upward from that serfdom into liberty, were it only the liberty of the farmer’s hind or the tailor’s journeyman? Therefore we must not restrict ourselves to the modern country labourer in this comparison; though, even under such restriction, it would still be difficult to regret the actual past. We must compare the medieval serf with the whole lower half of modern society; and the medieval country-folk in general with the whole of modern society except the highest stratum. From this truer standpoint, it is easier to reckon whether the centuries have brought as much improvement as might have been expected; and whether, if the modern wage-earner or his counsellors are tempted to deny that improvement, this is not because the modern proletariat has tasted the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, so that its very unrest is as true a measure of past progress as it is a true call to future efforts.

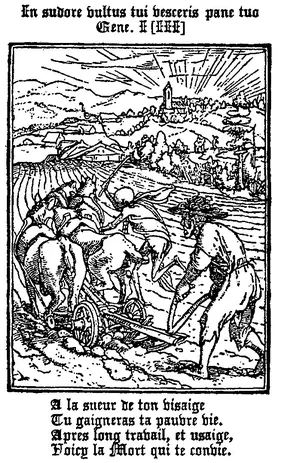

THE PEASANT

From Holbein’s Dance of Death

It is from this starting-point that I ask my readers to follow me in these chapters. If I emphasize the rural gloom, it is not that I am insensible to the rural glory. The sights, the sounds, the scents of English country life in the Middle Ages were all that they are pictured in William Morris’s romances, and a hundred times sweeter than prose or verse will ever tell. The white spring clouds spoke to the medieval peasant as they spoke to pre-historic man. Honesty, and love, and cheerful labour worked as a rich leaven in the mass of the country-folk ; the freshness of Chaucer’s poetry breathes the freshness of Chaucer’s England ; where things went well, there was a patriarchal simplicity which must command our deepest respect. All those things are true and must never be forgotten; but not less true are the things which are too often left unsaid1. Moreover, minds which search for all beauty everywhere will not be tempted to ignore the darker realities. The indignation of Ruskin and Morris was mainly laudable in their day; but will it not finally be seen that the highest of all artistic senses is that which, ceasing to rail at inevitable changes on the face of this universe, sets itself to make the best of them, in so far as they are inevitable? Must we not praise the mood of Samuel Butler recognizing the wonderful beauty of Fleet Street at certain moments? or of Mr J. C. Squire’s A House?—

And this mean edifice, which some dull architect

Built for an ignorant earth-turning hind,

Takes on the quality of that magnificent

Unshakable dauntlessness of human kind.

Built for an ignorant earth-turning hind,

Takes on the quality of that magnificent

Unshakable dauntlessness of human kind.

It stood there yesterday: it will to-morrow, too,

When there is none to watch, no alien eyes

To watch its ugliness assume a majesty

From this great solitude of evening skies.

When there is none to watch, no alien eyes

To watch its ugliness assume a majesty

From this great solitude of evening skies.

Ecclesiastes was right; “ God hath made every thing beautiful in his time: also he hath set the world in their heart, so that no man can find out the work that God maketh from the beginning to the end.”

CHAPTER II

VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT

LET us begin, then, by taking stock of the main points which differentiate medieval village life from that of today. We shall not need to reflect whether those older conditions were natural; for we shall see that, however strange to modern practice, they grew up quite naturally from the different circumstances of those times. We shall, however, ask ourselves more often whether these processes, however natural, were actually inevitable; and here, I think, we shall generally decide that they may have been avoidable in the abstract, but that we ourselves, under the same pressure of circumstances, could hardly count upon ourselves (or on our fellow-citizens as we know them), to follow any wiser and more far-seeing course than our ancestors followed. But, while acquitting the men themselves, we must weigh their institutions most critically; since easy-going indulgence to the past may spell injustice to the present and the future. We are anxious, and rightly anxious, about our wage-earning classes both in the towns and on the land; I suppose there are few who would not vote for socialism tomorrow if they could believe that socialism would not only diminish the wealth of the few but also permanently enrich the poor. We are deeply concerned with these questions; and there are some who preach a return to medieval conditions; not, of course, a direct return, but a new orientation of society which they hope would restore the medieval relation of class to class, and thus (as they believe) bring us back to a state of patriarchal prosperity and content.

This, then, brings us to a third, and very different, question; not only: Was the medieval village system natural? not only, again: Was it to all intents and purposes inevitable for the time? but, lastly, and most emphatically: Was it a model for our imitation? and, if so, to what extent? We can answer this best by looking closely into the life of the peasant six hundred years ago (say, in 1324), when he was neither at his worst nor at his best.

There is general rough agreement with Thorold Rogers’s verdict that, materially speaking, the English peasant was better off from about 1450 to 1500 than in the earlier Middle Ages, and, possibly, than in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries2. But in important details Rogers has been shown to be hasty or mistaken3, especially in his assumption that there was little unemployment; and, valuable as his work was in breaking ground, the question has been thrown into wider and truer perspective by a number of later writers4. The peasant had a long and weary way to go before he arrived at this comparative prosperity of the fifteenth century. The break-up of the Roman Empire had been terrible for all classes, but most terrible for the poor. The barbarian invasions strengthened and accelerated a movement which had already begun before the collapse of the Empire. Both from the personal and from the financial side, small men had been driven more and more to give themselves up to the great for protection’s sake. By the process called patrocinium, a man surrendered his person to a sort of vassalage; or, again, through the precarium, he made a similar half-surrender of his lands; or, thirdly, he might surrender both together to one whose protection he sought for both5. In certain countries and at certain times, such a richer landlord gained far more power over those who acknowledged themselves his “men” than the State itself could exercise; this is characteristic of that half-way stage between wild individualism and modern collectivism which we call the Feudal System. And the most characteristic product of that half-way stage was the serf, a person intermediate between the freeman and the slave6. This intermediate person was called by many different names at different places and times. I shall here call him indifferently serf or villein or bondman, terms which in our tongue were practically convertible in the later Middle Ages. Beaumanoir’s analysis of the causes of bondage, though not historically exhaustive, is of extreme interest as a chapter in thirteenth century thought. Freedom is the original and natural state of man; but “servitude of body hath come in by divers means.” First, as a punishment for those who held back when all men were summoned to do battle for their country; secondly, those who have given themselves to the church, as donati; thirdly, “by sale, as when a man fell into poverty, and said t...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON HISTORY, POLITICAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- Table of Contents

- ABBREVIATIONS AND AUTHORITIES

- CHAPTER I - THE OPEN ROAD

- CHAPTER II - VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT

- CHAPTER III - A FEW CROSS-LIGHTS

- CHAPTER IV - A GLASTONBURY MANOR

- CHAPTER V - THE SPORTING CHANCE

- CHAPTER VI - BANS AND MONOPOLIES

- CHAPTER VII - THE MANOR COURT

- CHAPTER VIII - LIFE ON A MONASTIC MANOR

- CHAPTER IX - FATHERLY GOVERNMENT

- CHAPTER X - THE LORD’S POWER

- CHAPTER XI - EARLIER REVOLTS

- CHAPTER XII - MONKS AND SERFS

- CHAPTER XIII - THE CHANCES OF LIBERATION

- CHAPTER XIV - LEGAL BARRIERS TO ENFRANCHISEMENT

- CHAPTER XV - KINDLY CONCESSIONS

- CHAPTER XVI - JUSTICE

- CHAPTER XVII - CLEARINGS AND ENCLOSURES

- CHAPTER XVIII - CHURCH ESTIMATES OF THE PEASANT

- CHAPTER XIX - RELIGIOUS EDUCATION

- CHAPTER XX - TITHES AND FRICTION

- CHAPTER XXI - TITHES AND FRICTION (cont.)

- CHAPTER XXII - POVERTY UNADORNED

- CHAPTER XXIII - LABOUR AND CONSIDERATION

- CHAPTER XXIV - THE REBELLION OF THE POOR

- CHAPTER XXV - THE REBELLION OF THE POOR (cont.)

- CHAPTER XXVI - THE DISSOLUTION OF THE MONASTERIES

- CHAPTER XXVII - CONCLUSION

- APPENDIXES

- POSTSCRIPTS

- INDEX

- DOVER BOOKS