eBook - ePub

What Light Through Yonder Window Breaks?

More Experiments in Atmospheric Physics

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Informative and engagingly idiosyncratic . . . brings the subject down to earth with offbeat, everyday examples and easy-to-follow experiments. . . . Both professionals and laymen can learn from this book."—The New York Times Book Review

"A brilliant collection of intriguing examples of the physics of everyday phenomena, with the examples presented as puzzles."—Discover

"A delightful book."—Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

This is the sequel to Craig Bohren's popular Clouds in a Glass of Beer (also available from Dover), the book that made the fascinating world of atmospheric physics accessible to readers without a scientific background. Like its predecessor, this volume abounds in lively writing, fun-filled and easy-to-perform experiments, and numerous photographs and illustrations that offer illuminating and memorable ways to learn about an intriguing branch of science.

"A brilliant collection of intriguing examples of the physics of everyday phenomena, with the examples presented as puzzles."—Discover

"A delightful book."—Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

This is the sequel to Craig Bohren's popular Clouds in a Glass of Beer (also available from Dover), the book that made the fascinating world of atmospheric physics accessible to readers without a scientific background. Like its predecessor, this volume abounds in lively writing, fun-filled and easy-to-perform experiments, and numerous photographs and illustrations that offer illuminating and memorable ways to learn about an intriguing branch of science.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Window Watching

I must go seek some dew drops here

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Grading examinations can be a painful reminder of the yawning gap between what students appear to know–a call for questions is almost always met with silence–and what they actually know. It’s usually tedious work, which I begin with a heavy heart and end with a headache.

At Penn State we give our graduate students a qualifying examination. The students hate to take it; the professors hate no less to grade it. We submit questions, they are sifted by a committee, the residue is inflicted on the students, then each question is graded independently by two professors. Once, I had to grade a question submitted by Toby Carlson, one of my colleagues. It lay on my desk for more than a week, and only after I had exhausted my excuses for not looking at this question did I reluctantly sit down to read it and the answers to it. The question was as follows: During the winter, dew often forms on windows, but always on their inside surfaces. Why?

I perked up when I read this. Suddenly, I was interested. Although I had seen dew on the insides of windows many times, I am ashamed to admit that I had never really thought about this before. Now I could think of nothing else.

More Is Not Always the Answer

As could have been predicted, the answers to Toby’s question contained vague statements about “more humidity” inside houses than outside, although the students were not always clear if they meant greater relative or absolute humidity. Absolute humidity is the actual density (molecules per unit volume) of the water vapor component of air. Relative humidity is the water vapor density relative to what it would be if it were in equilibrium with liquid water.

Relative humidities inside houses during winter, especially in the colder parts of the United States, are not high, as evidenced by sales of humidifiers, the sole function of which is to increase relative humidity. I learned this the hard way when some of our furniture cracked during one of our first winters in Pennsylvania. Then we bought a humidifier.

Firmer evidence that relative humidities inside houses in winter are usually less than those outside is easy enough to obtain. One morning when there was dew on the inside of our windows and the temperature inside our house was low, I measured relative humidities. The house hadn’t been heated since the evening before, and no one had cooked or bathed since then. The dry-bulb temperature inside was 12°C (54°F); the wet-bulb temperature was five degrees lower, which corresponds to a relative humidity of about 48 percent. Outside, the dry-bulb temperature was 1°C (34°F) and the wet-bulb temperature was two degrees lower, which corresponds to a relative humidity of about 63 percent. Thus higher relative humidities inside cannot be necessary for dew formation on the insides of window panes.

Although the relative humidity I measured inside was less than that outside, the absolute humidity was greater. Occupied houses have various sources of water vapor: people breathing, sweating, bathing, and cooking. Outside air that drifts inside is heated and has water vapor added to it. Yet whether it is the relative or absolute humidity that is greater is irrelevant to Toby’s question.

Why Does Dew Form on the Insides of Windows?

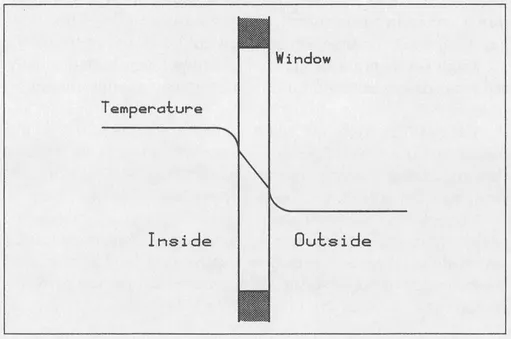

During the winter, temperatures inside houses are usually higher than those outside. Because of the continual transfer of energy from the warm interior of a house to its colder surroundings, the steady-state temperature profile in and near a window will be like that shown in Figure 1.1. The temperature of the inside surface of the window is less than the inside air temperature, whereas the temperature of the outside surface is greater than the outside air temperature. These temperature differences and the concept of dew point are the keys to understanding why dew forms on the inside of windows.

Figure 1.1

If the temperature inside a house is greater than that outside, and neither temperature changes with time, the temperature profile in and near a window will be as shown here. The rapid drop in temperature near both surfaces results from films of stagnant insulating air adjacent to them. Note that the inside window temperature is less than the inside air temperature, whereas the outside window temperature is greater than the outside air temperature.

The dew point is the temperature to which air must be cooled, at constant pressure, for saturation to occur. Stated another way, it is the temperature at which the rates of condensation and evaporation exactly balance; if air is cooled below the dew point, the balance is tipped in favor of condensation.

Usually, the air temperature is greater than, or at most equal to, the dew point. If the temperature of the outside window surface is greater than the outside air temperature, this surface is always above the dew point of the outside air; hence, dew cannot form on this surface. But the temperature of the inside surface may be lower than the dew point of the inside air; hence, dew may form on the inside surface.

The higher the relative humidity, the smaller the difference between the air temperature and the dew point. Although a higher relative humidity inside favors dew formation on the inside window surface, the essential reasons why dew forms on the inside rather than the outside surface are that in winter temperature decreases steadily from inside to outside a house and the air temperature is greater than the dew point.

For the outside surface of a window to be always warmer than the surrounding air, the window must not emit more infrared radiation to its surroundings than it absorbs from them (see Chapter 7 for more on infrared emission and absorption). Although this is probably true for most windows, which usually are vertical, it is not true for all surfaces, as you will discover in Chapter 9.

The qualifier steady state when applied to a temperature profile means that the profile does not change with time. If air warmer than the outside surface were to suddenly blow across a window, dew might form on it (although I never have observed this).

The process of dew formation on the insides of windows but not on their outsides may reverse during the summer, especially on windows of an air-conditioned house in a hot, humid environment. I have not observed this because I do my best to spend summers in cool and dry places.

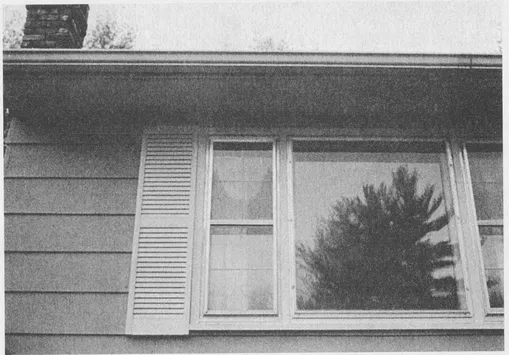

Dew Patterns on Windows

Once your attention has been drawn to dew on windows, you are likely to notice a wealth of details worth thinking about. For example, you might see a pattern like that shown in Figure 1.2. For months during the winter this symmetrical pattern persisted on the windows of a house in which we lived when I was on sabbatical leave at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Dew formed on only the bottom part of the window, and more toward the edges than at the center. Let us consider each of these observations in turn.

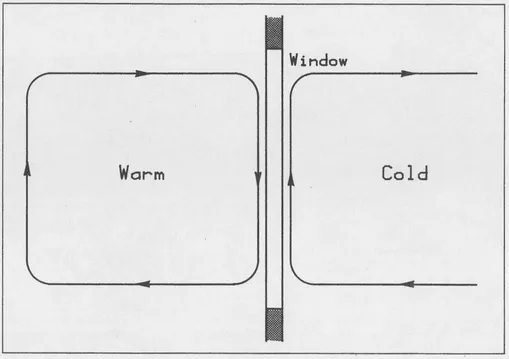

Air in contact with a window is not static. It moves under the influence of buoyancy (see Chapter 11). Cold air is denser than warm air if both are at the same pressure. Inside warm air that comes into contact with a colder window is cooled and therefore sinks. Let us imagine following a parcel of air as it descends along the inside surface of the window (see Figure 1.3). The parcel cools and the window is warmed. The rate of this warming is proportional to the difference between the window temperature and the parcel temperature. As the parcel descends, its temperature becomes closer to that of the window’s, so the rate of warming of the window by the parcel decreases as it descends. Outside, the air is colder than the window; hence, air that comes in contact with it is heated and rises. The rate of cooling of the window by a rising air parcel is proportional to the difference between the temperatures of window and parcel. This difference is greatest at the bottom of the window and decreases with height because the rising parcel is warmed by the window. Thus, because of circulation of both inside and outside air along the window, its temperature is least at the bottom and greatest at the top.

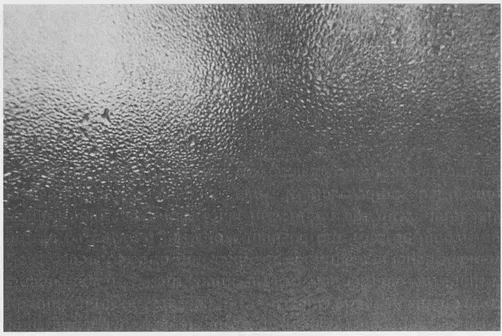

Figure 1.2

This symmetrical dew pattern on a window of a house sheltered from both wind and direct solar radiation was remarkably stable.

To verify that temperatures are indeed lower at the bottoms of window panes, I measured temperatures with a thermopile, which is a stack of thermocouples in series. A temperature difference between the junctions of a thermocouple gives rise to a voltage dependent on this difference. Windows emit infrared radiation, and the higher their temperature the more they emit. By means of this infrared radiation absorbed by the thermopile, I could measure temperatures over the window, although relative rather than absolute ones. I did this at night so that sunlight wouldn’t influence the results.

Figure 1.3

Buoyancy-driven flow near a window causes the window temperature to vary vertically, being higher at the top than at the bottom.

I first moved the thermopile horizontally, holding it close to the inside surface of the window. There was no noticeable change. But when I moved the thermopile vertically, the temperature it sensed changed markedly, the lowest value occurring at the bottom of the window.

Further evidence of lower temperatures near the bottoms of windows is provided by the size distribution of dew drops. I have noticed that often they are larger near the bottoms of windows, as in Figure 1.4.

What about the upward curve of the dew pattern toward the edges? This is more noticeable on small windows than on large ones. On my large picture window there was a noticeable upward curve of the dew line (the boundary between dew-covered and bare glass) near the edges but not so striking as that on the smaller adjacent windows. Again, I attribute this dew pattern to the imperceptible buoyancy-driven pattern of airflow over the window. Air near the frames is retarded somewhat by them, just as water flows slowest at the edges of a stream and fastest in the middle.

Figure 1.4

Drops are larger toward the bottom of this window, evidence that temperatures there are lower.

I discussed my observations of dew patterns with Bill Doyle, a colleague at Dartmouth. This prompted him to examine his windows. He noticed patterns different from those on mine. Instead of curving upward near the window edges, the dew line curved downward. And near the edges there were thin strips of bare glass. He attributed this to heating of the window frames by solar radiation. Frames are not nearly so transparent to such radiation as is glass. Thus glass adjacent to the frames is warmer than it would otherwise be, sufficiently so that dew does not form there.

As I mentioned previously, the dew patterns I observed were remarkably stable. Every morning they appeared to be about the same, no doubt because our house was in a hollow, sheltered both from wind and from direct solar radiation (especially the front of the house where I made most of my observations). With the coming of higher temperatures in spring and a shift in the direction of the sun, the dew patterns changed markedly. I ...

Table of contents

- DOVER SCIENCE BOOKS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 - Window Watching

- 2 - Interference Patterns on Garage Door Windows

- 3 - Window Watching and Polarized Light

- 4 - Fame from Window Watching: Malus and Polarized Light

- 5 - Light Bulb Climatology

- 6 - Highway Mirages

- 7 - The Greenhouse Effect Revisited

- 8 - Boil and Bubble, Toil and Trouble

- 9 - An Essay on Dew

- 10 - Mad Dogs and Englishmen Go Out in the Midday Sun

- 11 - Temperature Inversions Have Cold Bottoms

- 12 - Water Vapor Mysticism

- 13 - Strange Footprints in Snow

- 14 - The Doppler Effect

- 15 - All That’s Best of Dark and Bright

- Selected Bibliography and Suggestions for Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access What Light Through Yonder Window Breaks? by Craig F. Bohren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.