- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Nature of Visual Illusion

About this book

Fascinating, profusely illustrated study explores the psychology and physiology of vision, including light and color, motion receptors, the illusion of movement, much more. Over 100 illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Nature of Visual Illusion by Mark Fineman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Human Anatomy & Physiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. A Light and Color Primer

Almost everyone has seen color samples in a paint store, those small squares of color arranged in neat progessions on cards. A paint manufacturer provides his customers with several hundred samples at most, but imagine for a moment that someone set out to create every possible color that the human eye could distinguish. How many colors would there be? Thousands? Tens of thousands? Actually, the number of discriminably different colors has been estimated to be about 7.5 million!

How is that possible? Are there over seven million different kinds of receptors in the eye? Is light itself made up of millions of colors? Color vision is a good topic with which to start an examination of visual perception because it illustrates many of the complexities peculiar to the larger subject of vision. Before we try to understand the workings of color vision, however, it would be a good idea to consider a few fundamentals of vision.

VISUAL PERCEPTION

In the simplest of definitions, visual perception can be reduced to three events: 1. the presence of light, 2. an image being formed on the retina, and 3. an impulse transmitted to the brain.

1. Vision requires a stimulus. This stimulus is normally in a form of energy called light. Although sometimes a person claims to see in the absence of light, as in a dream or hallucination, these are special instances that do not pertain to the immediate discussion.

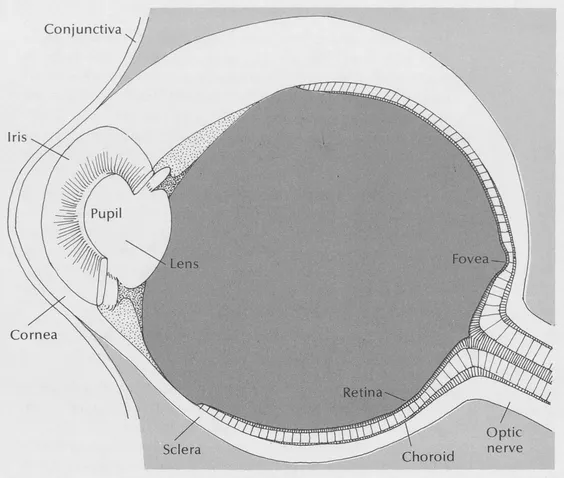

2. The light stimulus enters the eye, where it is refracted (bent) in such a way that an image is formed on the interior of the eye, a light sensitive surface known as the retina. The image-forming parts of the eye are the cornea, a clear bulge at the front of the eye, and the lens, located within the eye a short distance behind the cornea. You can see someone else’s cornea by asking that person to stare straight ahead while you observe his eye from the side.

The eye is a light-tight chamber except for the structures through which light enters. The cornea and lens refract the incoming light so as to form an image on the photosensitive interior layer of the eye, the retina. The pupil is a variable aperture whose diameter is regulated by the surrounding iris in response to the level of light in the environment.

The iris and pupil mechanism, interposed between cornea and lens, regulates the overall level of light that enters the eye. In bright light the pupil constricts, and in dim light it dilates. The pupil itself is an aperture whose diameter is controlled by the surrounding colored iris. The lens and the retina are on the interior of the eye and cannot be seen just by looking at the exterior of another person’s eye.

The retina is composed of millions of specialized receptor cells, as well as other types of cells that support the transmission from the retina to the brain. The receptors respond to the light striking them (the image) by triggering a chain of chemical reactions. It is this series of chemical changes that is transmitted from cell to cell, from retina to brain.

3. Thus the third event is the transmission of this chemical impulse to the brain, causing further chemical changes in the billions of cells that constitute the brain. These alterations in brain activity are unquestionably at the core of our responses to light, responses that can be conveniently categorized as “seeing.”

To summarize then, any time we talk about visual perception, three events must occur: a stimulus, an image, and the transmission of the impulse to the brain. Because of this, an analysis of any visual phenomenon—including color vision—can be made at one or more of these levels. In this chapter I would like to pay particular attention to some basic features of color vision, while at the same time noting some general features of visual perception.

LIGHT AND COLOR

The visual stimulus, light, is one manifestation of electromagnetic energy, which also encompasses such familiar phenomena as X rays, and radio and television transmissions.

Electromagnetic energy can be pictured as having the regular undulations of a wave, one whose distance from peak to peak may vary. For this reason it is common practice to describe an electromagnetic phenomenon in terms of its wavelength. If electromagnetic energy were arrayed according to wavelength, from shortest to longest, so as to form a spectrum, X rays would occur at the short end, broadcast bands would be at the long end, and the waves to which vision responds (visible light) would occupy an intermediate position. In fact, the wavelengths of visible light vary from about 300 to 700 nanometers. Since a single nanometer is a mere billionth of a meter long, it can be quickly appreciated that waves of visible light are still quite short.

In addition, electromagnetic energy (including visible light) has particle properties. When applied to light, a particle or quantum of energy is called a photon. This photon is often conjectured to be like a tiny packet of energy, one that oscillates in waveform as it travels.

No one is entirely certain why it is that we respond exclusively to the relatively tiny portion of the electromagnetic spectrum occupied by visible light. Some theorists have speculated that since these wavelengths are abundant in the sun’s radiations, it is reasonable to suppose that we would have evolved to be sensitive to them. It should be noted that some species of animals actually respond to slightly longer or shorter wavelengths than those of visible light.

Light at different wavelengths within the visible part of the spectrum varies in color. Longer wavelengths look red and shorter wavelengths look blue. Surely everyone is familiar with Sir Isaac Newton’s classic experiment: In an otherwise darkened room, a beam of sunlight was allowed to pass through a slit in a window-shade. The beam then passed through a glass prism and finally on to a screen. The prism had the effect of separating out the component wavelengths of the original beam of white light (light which contained all wavelengths in roughly equal proportions), creating a spectrum of visible wavelengths. Nature repeats substantially the same experiment whenever a rainbow appears.

Thus we can see a basis for color vision in the stimulus itself, and one might be inclined to assume that color vision is largely a matter of detecting various wavelengths of light. Even though this hypothesis is attractive, it still cannot account for the complexity of color vision. Remember that there are only about 400 wavelengths of visible light, yet we see millions of color tints and shadings. Even if we could discriminate every wavelength of visible light, we could account for the perception of no more than a few hundred colors at best.

INTENSITY AND BRIGHTNESS

The intensity of light is a measure of its energy. It is calculated by multiplying the frequency of light by a constant, named for the eminent German physicist Max Planck who discovered it, and which is therefore called Planck’s constant. Now you might suppose that if the energy of light were increased, we would always report that the light appeared brighter. In fact, however, the brightness of an object is only partially related to the energy of the light given off by that object. The intricacy of the intensity-brightness relationship is implicit in the word brightness itself, since brightness refers to how people see or respond to the energy dimension rather than to the energy itself. You may find it convenient to think of brightness as a measure of perceived intensity. Many researchers consider brightness perception to be an integral part of color vision.

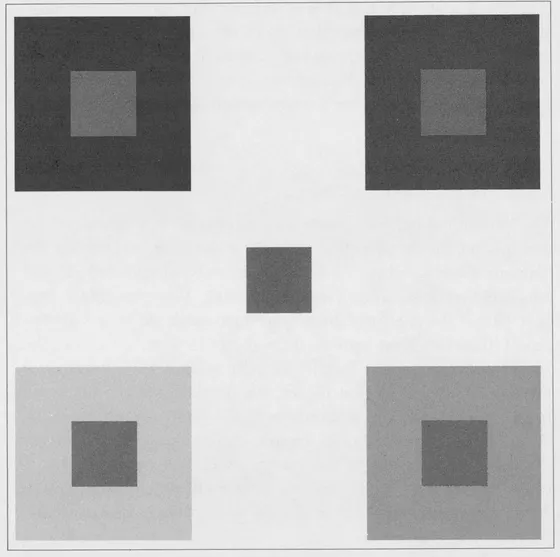

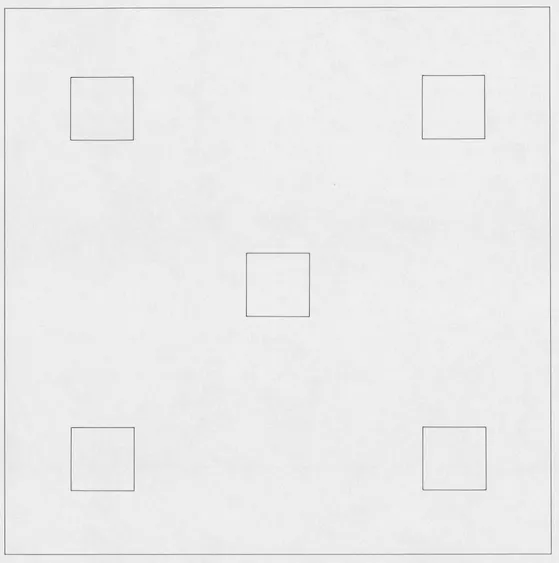

Why has it been necessary to construct this confusing concept of brightness? Why not stick with a straightforward measure of light energy? One reason is shown in the accompanying illustration, in which several gray squares are enclosed by larger squares. In every case the interior squares reflect equal levels of light to the viewer’s eyes, a fact that could be easily verified by measuring them with a light meter, or by inspecting the interior squares without the surrounding squares. For example, cut out the white mask and place it over the illustration so that only the inner squares can be seen. When viewed against the uniform white background, the interior squares should appear equally bright. Even though the inner squares are of equal intensity, they nonetheless appear to be of unequal brightness values when the surrounding squares are in view. This contrast effect is attributable to the viewer’s own visual system and will be discussed again in later chapters.

Simultaneous contrast. Even though all of the enclosed squares are of equal intensity, they appear to be of different brightnesses. By cutting out the white mask and placing it over the squares so that only the interior areas show through, you will see that they do indeed reflect equal intensities.

One of the reasons that color vision is so difficult to fathom is that both the nature of light and the nature of the observer’s visual system must be considered, as these illustrations may have already suggested. Therefore, let’s turn to some of the complications created by the interaction of stimulus and observer.

COLOR MIXING AND COLOR VISION

More than a century ago, Thomas Young, the English physicist and physician, suggested that lights of any three different colors may be combined to create all of the remaining colors of the visible spectrum. For example, if a beam of green light is projected on to a white screen, and a beam of red light is made to overlap the first beam on the screen, the overlapped region will appear yellowish. Thus three lights and their combinations are all that would be needed to create all of the colors of the visible spectrum. In the red and green example, the receptors of the retina are stimulated by wavelengths at two locations on the spectrum, and so this is an example of an additive color mixture. (Additive mixtures are typical of the human eye.)

Most people, however, are more familiar with a subtractive color mixture such as the type that occurs when paints or pigments are combined. Mixing blue paint with yellow paint yields green. It is called a subtractive mixture because the combination of paints acts to absorb light in certain portions of the spectrum while allowing light at the remaining wavelengths to be reflected to the eye.

The important consideration is that only three colors and their combinations are needed to create all of the spectral colors. Young further theorized that there need be only three types of color receptors in the eye, each responsive to a different portion of the spectrum. Their combined activity could then account for the remaining colors. This trichromatic theory of color reception has now been amply supported by the evidence of many laboratory studies, and there is no need to postulate the existence of scores of different cell types in the retina—let alone millions—in order to account for color vision at the level of the eye.

On a more practical level, our knowledge of color mixture and color vision has made color photography possible, as well as color television and color printing. Color film, for example, is a sandwich of three photosensitive layers, each of which reacts chemically to a different portion of the spectrum. The mechanism by which color film operates is therefore analogous to that of the color receptors in our eyes.

COLOR INTERACTIONS

Although the trichromatic theory helped to simplify our understanding of color receptors, it didn’t answer all the questions. There are some colors that do not appear in the spectrum arrayed by Newton’s prism. Where do colors like pink and brown fit in? Metallic colors (such as silver and bronze) and shades of gray also bear no obvious relationship to the spectrum.

Part of the answer lies in the fact that colored light may be combined with white light to varying degrees. Red light combined with white light will appear lighter, more “pinkish.” The grays are a function of intensity of white light and can only be seen as surfaces, not in lights.

Colors can also interact in many ways. One way to see a color interaction is to repeat the earlier contrast demonstration substituting colored paper squares for the gray patches. Any kind of uniformly colored paper will do. Cut out several squares of the same color (a pale green works well) and see how the squares compare when placed against patches of other colors. You should be able to detect subtle differences in brightness, as before, but also slight differences in tint as well.

COLOR CONSTANCY

Understanding color vision is also complicated by a characteristic of observers called hue constancy or color constancy. So far we have assumed that the light ordinarily illuminating our environment is white light, containing roughly equal proportions of light from all of the visible wavelengths. In actuality white light is the exception rather than the rule. Sunlight only approaches the white standard around noontime. At other times of the day its spectral composition is more varied due to the filtering properties of the atmosphere; sunlight passes through varying thicknesses of atmosphere at different times of the day, and the color of sunlight may be affected by dust particles and pollutants suspended in the a...

Table of contents

- DOVER SCIENCE BOOKS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- 1. A Light and Color Primer

- 2. The Minimum Case for Vision

- 3. Completion: - Phantoms of the Visual System

- 4. Motion Receptors

- 5. The Illusion of Movement

- 6. The Wagon Wheel Effect

- 7. Motion Perception: - Learned or Innate?

- 8. Kinetic Art

- 9. More Kinetic Depth

- 10. Leonardo’s Window

- 11. The Size Problem

- 12. Two Eyes Are Better than One

- 13. Pulfrich’s Amazing Pendulum

- 14. The Anamorphic Puzzle

- 15. The Probability of Form

- 16. The Restless Eye

- 17. Bands, Grids, and Gratings

- 18. Color Curiosities

- 19. Poggendorff’s Illusion

- Annotated Bibliography

- Index

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST