Chapter 1

1885–1887

Trials of a Working Girl

Now and then a young woman with keen sense of the world’s movements, who writes well, will look longingly to a great city paper with a desire to become one of its workers.

—Good Housekeeping, 1890

Somewhere in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, in early 1885, a twenty-year-old woman chose her words carefully. Across the river, past the barges sliding by heaped with coal, the industrial engine of Pittsburgh churned out steel beams and glass bottles. Surrounded by hills that trapped the factory pollution, Pittsburgh was the “City of Smoke.” Residents said it with pride; smoke equaled money. And the metropolis had money, but not much glamour, as the thick air smeared white gloves with ash. Not far beyond city limits, the tall buildings turned to hard-to-traverse hills and deep forest. Evergreen branches bent under heaps of snow, isolating the small towns, the kind where the young woman had grown up. But she was older now, and that day, on a large sheet of paper, she penned a letter to the editor of the Pittsburg Dispatch, hoping to write herself into a new life.*

The Dispatch was a prosperous, forward-looking paper, known for opposing slavery during the Civil War and favoring increased rights for women. But one of the paper’s columnists, Erasmus Wilson, who used the pseudonym the “Quiet Observer” and usually covered topics like the etiquette of umbrella usage, had recently taken the “women’s sphere” as his theme. It was a topic hashed over in articles and lectures of the 1880s as suffragists urged that women should take part in public life—inventing, reforming, voting—while conservatives argued that they belonged in the home. But the suffragists had encountered a series of setbacks. Passed in the wake of the Civil War, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had given citizens the right to vote regardless of race, but the Fourteenth Amendment had specified that the right belonged to “male citizens,” the first time sex appeared in the Constitution as a voting criteria. Efforts to pass an amendment to allow for female voters had languished in Congress every year since the proposal was introduced in 1878.

Wilson joined those who felt biology and the Bible framed the female for domestic life. His columns expressed increasing annoyance with those who sought to expand their reach. “If women would just let up on this sphere business and set themselves to do that which they are best fitted for, and which their hands and hearts find to be done, they would achieve more for themselves and be greater blessings to the world,” he wrote. A woman’s focus should be making “her home a little paradise, herself playing the part of angel.”

In January 1885, the Quiet Observer pushed his point even further. A man calling himself “Anxious Father” wrote in, asking what to do with his five daughters. In their teens and mid-twenties, they painted, collected money for the poor, played piano, but didn’t seem fit for much else. He’d love to marry them off but didn’t have many takers: “Now what am I to do with them?”

Wilson was remarkably unhelpful, suggesting that the father ask the Dispatch’s female columnist Bessie Bramble instead and noting, darkly, that in China they kill extra girl babies or sell them as slaves. When the father wrote Wilson back, unsatisfied with Bramble’s advice (she idealistically suggested that in this modern age, there were no limits to what women could achieve, while Anxious Father saw limits everywhere), Wilson doubled down, stressing that the sooner a woman found a husband and got on with the business of housekeeping, the better. A woman who ventures outside her sphere and competes with men is “abnormal,” “a monstrosity.” If Wilson was playing the gadfly, it worked. Women wrote in, incensed, saying, “Your ‘Quiet Observer’ is a fool—to put it mildly. I used to like him real well, but since he got onto this woman question he is just as crazy as the rest of the men,” and “We don’t wish to wear the breeches, we simply want our rights, and that is to dispose of ourselves according to our own sweet wills.”

For the young writer in Allegheny City, this idea of domestic bliss directly contradicted her personal experience. She’d heard her mother called “whore” and “bitch” by her alcoholic stepfather and watched as he choked her. Marriage made her mother wish she was dead. At fourteen, the girl fled the house, along with her younger sister, mother, and brother, when the stepfather leaped up from a dinner table argument, brandishing a gun. Over the course of several days, the stepfather barricaded himself inside and destroyed their home, smashing furniture and flowerpots, upending the table, kicking holes in wall plaster. Hard to play an angel in this domestic paradise.

She wanted something more, but what? Teaching was an option for smart young women, and so she’d started at Indiana State Normal School with high hopes. Her father left some money when he died, but the executor mismanaged it, and funds ran out after one term. She found herself back home. Factory worker, servant, shop clerk—fields open to women—had applicants lined up to apply. In the Dispatch’s Help Wanted section, things looked equally bleak. The city was recovering from a nationwide recession marked by a stock market crash, meager prices on corn and wheat, and a bank panic that shuttered the Penn Bank in Pittsburgh and left the streets crowded with the unemployed. So listings were thin. But still, that January, in the “Male Help” column readers could find:

“Wanted–manager for art publications for the best house in the trade.”

“Wanted–Experienced press boy–that can make himself generally useful in a printing office.”

“Wanted–Agents in every county in Western Pennsylvania, Western Virginia and Eastern Ohio, to sell the celebrated Electric Light Lamp.”

But reading farther down to the “Female Help” listings, job seekers would find only:

“Wanted–Two good dishwashers at Horner’s Chophouse.”

“Wanted–a good girl for general housework.”

“Wanted–a chambermaid, from 25 to 40 years of age; one that can make good soup.”

The letter writer saw herself in Anxious Father’s daughters. How frustrating to be brushed off as useless when she had so much to offer. It wasn’t fair.

The young woman, called “Pinkey” by friends and relatives, wrote the newspaper to say so. Her writing style was unpolished, to say the least, punctuation haphazard as hail, but she made a passionate argument, rooted in a real situation—her life. She wrote about applying for jobs, being treated badly and rejected over and over. She was too small. They didn’t have any openings. The pay for women was less than half what a man might make, nothing one could live on. She signed it “Lonely Orphan Girl” and sent it off.

Flipping through the Dispatch several days later, she didn’t find her letter, but this instead:

“If the writer of the communication signed ‘Lonely Orphan Girl’ will send her name and address to this office, merely as a guarantee of good faith, she will confer a favor and receive the information she desires.”

The next day, a girl who struck those she passed as shy and rather frightened showed up at the offices of the Pittsburg Dispatch, out of breath from climbing the four flights of stairs, and asked to speak to the editor. Her meek voice and timidity were in contrast to her clothes—a floor-length silk cape and a fur turban—which projected, if not grandness, at least the idea of grandness.

Under her plush hat, the girl had hair cut with bangs, a round face, and a snub nose that would later be described as evidence of “a strain of sound North Ireland in her stock.” Elizabeth Cochrane (originally “Cochran,” but she added a final “e” to sound more distinguished), struck people, then and later, as not so much as beautiful but straightforward. There was nothing vague or unfocused about her curious glance. She asked for what she wanted. The editor, who had been impressed by the personality in her prose, despite the rough edges, hired her to write two articles. A working-class young woman would add a missing perspective.

Her first column, a direct response to Wilson’s dialogue with Anxious Father, was called “The Girl Puzzle.” Not all women marry, and not all have the skills, money, beauty, or connections to succeed as writers, doctors, or actresses, she wrote. The white-haired columnist’s fantasy home life obscured the reality for many. She also pushed back against the abstract optimism of Bramble, who had painted endless possibilities for women, while in her view, there were hardly any. What women needed, she said, were better jobs. Why not have female messengers or office assistants, and allow them to work their way up as a young man might? Why couldn’t girls be Pullman conductors or traveling salesmen? After all, she wrote, “Girls are just as smart, a great deal quicker to learn.”

Her second article, “Mad Marriages,” argued for a law that would bar anyone who had taken public charity, or owed taxes, from marrying. At her mother’s divorce proceeding, neighbor after neighbor testified that they’d known for years the man she married had a foul temper and propensity to drink. They should have been required to speak up before the ceremony, the writer suggested. And divorce should be outlawed, so that people wouldn’t just leap into a wedding, ignoring warning signs. All these steps would keep the unhappy spouse from saying “I did not know,” and allow the community (and perhaps frustrated daughters) to say, “I told you so.” For this piece, she dropped “Orphan Girl,” and picked up the pseudonym “Nellie Bly,” a nod to a song by Pittsburgh native Stephen Foster.

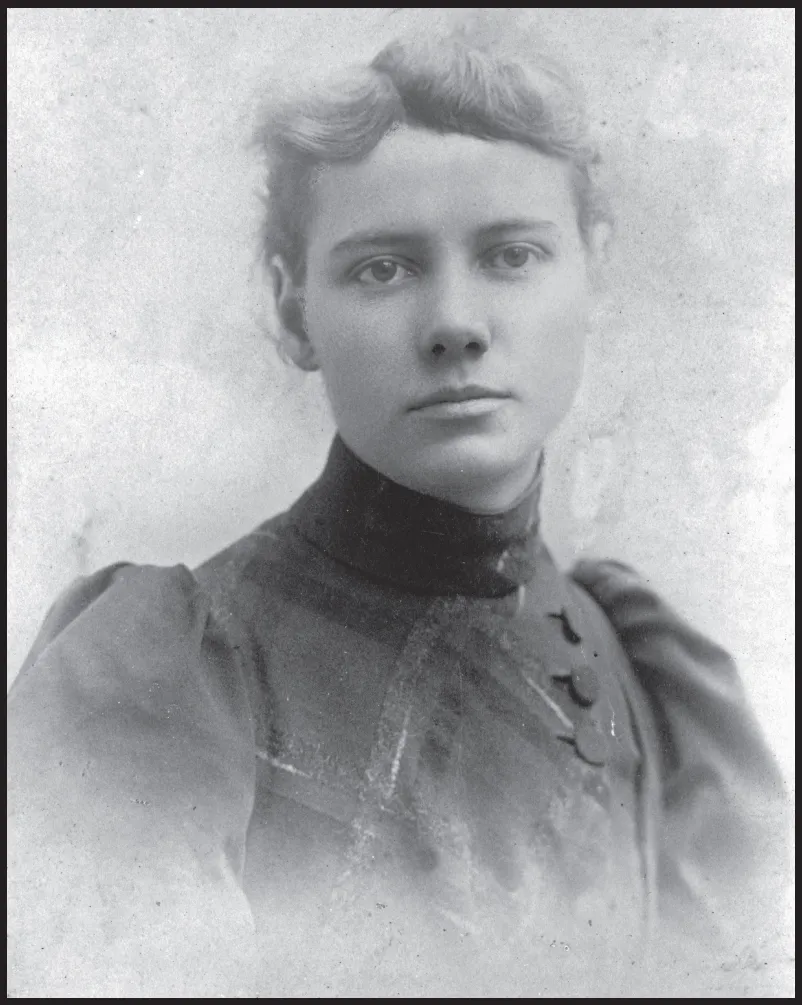

Elizabeth Cochrane, “Nellie Bly”

Elizabeth Cochrane, “Nellie Bly,” head-and-shoulders portrait c. 1890. (Library of Congress)

Through the late winter and early spring, Bly wrote a series on “Our Workshop Girls.” Week after week, she interviewed women making money in fields beyond cleaning and cooking. Unlike her pieces that would come later, exposing harsh factory conditions, Bly’s implied argument was that women could do a lot more than generally thought, and do it well. She profiled women contributing to Pittsburgh’s most iconic, manly industries, immersed in dirt and flame: the iron works, the wire works, the glassworks. These surprising stories, and her energetic recounting of them, spread beyond western Pennsylvania. The Dispatch’s New York correspondent copied the idea, noting that Bly’s series “attracted considerable attention here.”

It quickly became clear that behind the timorous girl who turned up and painted herself as a representative of the ordinary and unexceptional lurked someone else entirely, someone deeply determined. Not long after the Dispatch hired her, Bly found herself pushed into the society journalism traditionally offered to women. Reports on spring fashions and flower shows were painfully boring, and she took off to Mexico for six months as a correspondent, writing about hotels and cuisine, but also poverty and prison conditions. After Mexico, she gave Pittsburgh-based reporting another try, but her mind drifted elsewhere. Finally, in spring 1887, Bly wrote a goodbye letter to Wilson (who became a close friend, despite his infuriating on-paper attitudes), left the smoke and comfort of western Pennsylvania behind, and went to seek her fortune in New York City, home of legendary newspapers like the Tribune, founded by Horace Greeley; Charles Dana’s Sun; and, most significantly, Joseph Pulitzer’s World.

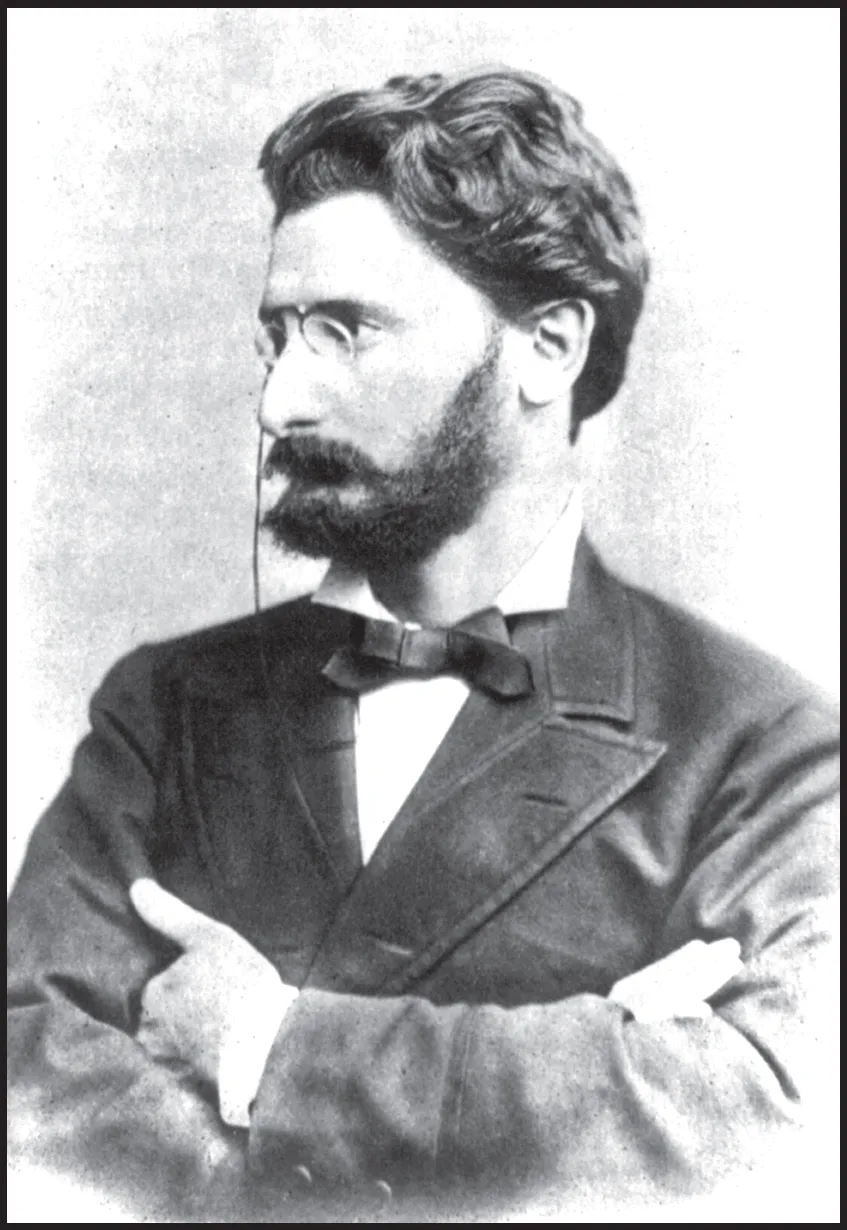

Gangly with poor eyesight, Joseph Pulitzer had come to the United States from Hungary in 1864 to fight for the Union in the Civil War as a seventeen-year old. He then spent hard years scrambling for a job—tending mules, waiting tables—until making his way in the newspaper business, first as a reporter for the German-language newspaper in St. Louis, and ultimately as publisher of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. It was here that he honed his ideas about the kind of paper he wanted. Positioning the Post-Dispatch as a friend of the common man against rich corporations, he published the tax returns of the wealthy to show they weren’t paying their share and campaigned against railroad monopolies. He experimented with a different kind of storytelling, conducting investigations of gambling dens and fortune-tellers, sending a reporter to find a killer who had eluded the police (with no luck), and pushing his writers toward crisp, compact prose. As an editor and publisher, he was always in the office, always offering an opinion. His unruly dark beard was cropped close to his jaw when he was a younger man but, when he was older, flowed down his chest like that of a Victorian genius.

Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer, 1911; Joseph Pulitzer at 40. Head and shoulders, arms crossed, facing left, glasses, beard. (Library of Congress). https://www.loc.gov/item/2007682378/.

In 1883, drawn to publishing’s epicenter, he moved to Manhattan and bought the struggling New York World. A year earlier, his younger brother Albert had launched the 1-cent paper the Morning Journal in the same city. The Journal aimed for a “sparkling, breezy, good-natured tone” specifically to appeal to women and their advertising dollars. Failing to get a loan from his brother, Albert did a fundraising tour in Europe, came home with $25,000, and rented space and printing presses from the New-York Tribune. With its low price and coverage of dances and love affai...