![]()

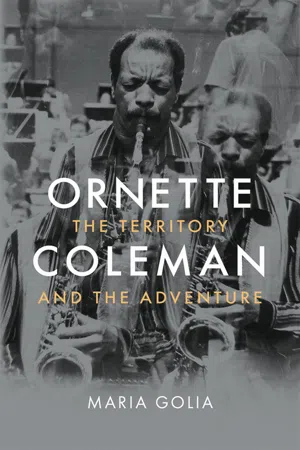

Part One: Coming Up

Jazz is existence music. It puts you in the world.

WYNTON MARSALIS

However integral narratives may have been to the nation’s foundation, none of the United States produced as robust a narrative as Texas. The frontier settlers’ Texas Revolution, a battle for independence from Mexico that resulted in the establishment of a Texan republic (1835–45), contributed to its freedom-loving élan. The vastness of the territory, considerably larger than Ukraine or mainland France, and the promise of wealth it so amply fulfilled ensured its iconic status. Encompassing prairies, grasslands, forests, coastal swamps, natural harbors, sandy beaches, piney woods, and vast tracts of desert and mountains, Texas held the allure of undiscovered possibilities. In this and other ways it was America in microcosm, at its best expansive, liberating, enterprising, a place where courage and individuality served the greater good; at its worst insular and paranoid, pioneers circling the wagons, waiting for the cavalry to shoot their way out. Many attributes comprising the American self-image are Texan by association if not origin: resilience, pride, individuality, common sense, and entitlement to as much of everything as possible. And in this land of plenty, no state gave more abundantly of its nation- building flesh and blood, red meat and crude oil.

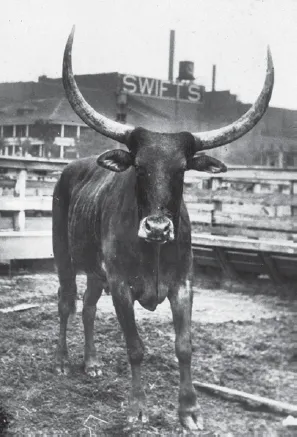

All blessings came from the land, beginning with the cattle that arrived with the Spanish missionaries and conquistadores in Christopher Columbus’s wake and were left to multiply, undisturbed, on the open range. By 1860 Texans were outnumbered six to one by quarter-ton longhorns, feral descendants of the calves and heifers that crossed the Atlantic. When the railroads brought the market within a thousand-mile reach, the rangy longhorn distinguished itself by its ability to thrive, camel-like, on the long march. The forced migration of over six million head in the late 1860–70s took place along the Chisholm Trail, running due north from the Texan heartland to a railhead in Abilene, Kansas. Among the towns offering respite en route, Fort Worth was the most anticipated, the “Paris of the Plains,” famed for its saloons and brothels.

Peopled by the neotypes of American mythology—wranglers, sports and demimondes, card sharks, stage coach, train and bank robbers, Wyatt Earp and the Sundance Kid—Fort Worth’s downtown district was called Hell’s Half Acre, where outlaws did real and metaphysical battle with the defenders of order who kept one hand on the Bible, the other on the trigger of their guns. The unbridled testosterone that fueled the Acre’s narrative was soon redirected towards commerce. The arrival of the Texas and Pacific Railway in 1876 transformed Fort Worth from a stopover to a destination; the establishment of the Swift & Co. meatpacking companies in 1902 caused its population to triple. Fort Worth became America’s beef factory and its sprawling stockyards and slaughterhouses made the city’s first large, legitimate fortune.

“Other states were carved or born / Texas grew from hide and horn,” wrote poet Berta Hart Nance, and while it is true that Fort Worth merits the sobriquet “Cowtown,” it was originally, as the name implies, a military outpost. Established in 1849 and tasked with protecting settlers, Fort Worth was disruptively situated beside the game-rich banks of the Trinity River, a well-known Native American hunting ground; its founding officers had farms, killed “injuns,” and kept slaves. A courthouse had replaced the fort in the late 1870s and over the next half-century a low-slung skyline, dominated by the courthouse steeple, etched itself against the horizon. Seen from above, Fort Worth juts from the featureless plain like a skeletal reef on the floor of a vanished sea. The torpor of its blazing summers helps account for the spare, languidly cadenced dialect, the parched brush sprouting along roads, the wide-brimmed ten-gallon hats favored by inhabitants, the sound of crickets at night, the buzz of flies in the daytime; Fort Worth was neither urban nor rural. Prone to savage tornadoes, floods, and freakish storms, its uneasy truce with nature was mirrored in the ambivalence of society. In Ornette Coleman’s recollection:

Longhorn steer in livestock pen at the Swift & Co. stockyards, Fort Worth, c. 1940s.

Sometimes the sun is shining and beautiful on one side of the street, and across the street, just maybe three feet [1 m] apart, there’d be big balls of hail and thunderstorms, and that reminded me of something that happened with people . . . they’re the same way as the elements.1

At the time of Ornette’s birth, Fort Worth was a mix of the small-town ordinary and the larger-than-life, a city of us and them, the powerful and those who served at their pleasure.

OWING TO ITS frontier history, Fort Worth considered itself culturally western as opposed to southern, a place where individual freedom was valued and the race issue handled more genteelly than in the Deep South. While no lynching of African Americans was recorded there, historic attitudes may be judged by the 1860 hanging of two white abolitionists (who advocated an end to slavery) at the hands of Fort Worth’s “Vigilance Committee.” Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was late in reaching Fort Worth, but on June 19, 1865, when General Gordon Granger delivered the news, “there was no jubilee of freedom” or “reports of a mass exodus of freedmen.”2 After the Civil War, the Texas legislature’s “black codes” restricted movement, property ownership, and labor contracts not only to all visibly African Americans, but to so-called “octoroons,” anyone with a single black grandparent, that is, an eighth of African heritage.

In 1868 a branch of the Ku Klux Klan opened in Fort Worth shortly after the one established in Dallas. With black lives held hostage to punitive laws, white populations openly enacted race hatred. Between 1900 and 1920 some one hundred African Americans were publicly tortured and murdered in Texas.3 These crimes were sometimes perpetrated in broad daylight amid a cheering crowd, photographed, and made into souvenir postcards. “This is the Barbeque we had last night” reads the script on the back of a postcard sent from Robinson, Texas, in 1916, referring to the charred corpse of a man depicted on the front.4

Despite its wide-open spaces and the independence and individualism that Texans wished to embody, the “Lone Star State” was trapped in the same racist norms as the claustrophobic South. If Fort Worth was less guilty of violence towards blacks than other cities, including neighboring Dallas, the possibility of such violence was ever present. Fort Worth prided itself on relatively calm race relations largely because its black population was small and powerless enough to pose minimal threat; white residents tended to ignore black communities altogether and African Americans entered their lives almost exclusively as employees. The tensions that arose from the contradiction between self-myth and reality defined this society and arguably fueled its vibrant and progressive music scene. In black communities, music offered a means of self-improvement and expression, and livelihoods were earned through teaching and performance.

In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation was not discrimination, so long as the racially separate facilities were “equal,” a word whose meaning was broadly interpreted in the raft of laws issued throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. “Jim Crow,” the name of a blackface minstrel performer, became the shorthand term for practices projecting the appearance of equality while maintaining a racist status quo. In 1930, when Ornette Coleman was born, Fort Worth, a city of 163,000 people (including approximately 22,000 African Americans and 4,000 Mexican Americans), was thoroughly segregated: schools, hospitals, restaurants, hotels, public transport, and neighborhoods. Blacks were obliged to travel in separate train cars and railroad stations were equipped with separate waiting rooms. African American citizens could visit the city’s parks only on “Juneteenth” (June 19th), the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation’s arrival in Texas. They were either altogether barred from sports or cultural events, or able to attend only when separate seating and restrooms were provided. The 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition (June 6–November 29), an extravaganza held in Dallas marking one hundred years of Texas independence, featured a “Hall of Negro Life,” “the first recognition of black culture at a world’s fair,” which blacks were allowed to visit only on “Negro Day.”5

Main Street, Fort Worth, Texas, in the late 1920s.

In Fort Worth, African Americans had to step off the sidewalk when white people passed and to address them as “Ma’am” or “Mr.” if not “Sir.” Profit occasionally trumped prejudice: Leonard Brothers, one of Fort Worth’s several large department stores, courted a black clientele while maintaining the obligatory “colored” restrooms, drinking fountains, and seating in the store’s cafeteria. Mexican Americans fared slightly better; while “unofficial” discrimination relegated them to an inferior social position, they could, for example, be buried in white cemeteries, whereas African Americans had their own separate but equal ones.6 Nor did white Christians feel that Galatians 3:26 (“[We] are all the children of God by faith in Christ Jesus”) applied to black Christians, who in any case had long established their own churches in order to worship as they pleased.

That segregation was an artificial means of negotiating deeply racist attitudes is clear in hindsight; the burden it represented to African Americans denied their dignity at every turn is less easily grasped. The word “denigration” (from the Latin “to blacken”) has been simplistically associated with racial prejudice, but its significance lies in its connotation of darkness, the kind that envelops the soul of individuals whose self-esteem has been ceaselessly battered. Consider the pervasive shadow that racism cast on black communities, augmented by the hardships of the Great Depression, when an estimated 50 percent of African Americans were unemployed, and one may begin to approach the importance of the Church as refuge. Centers of moral and material support, education, and cultural affirmation, churches provided a platform for community organizations and formed the backbone of the nascent black middle class.7

In all the world throughout all time, there has never been a surer means of wringing exaltation from the heart of despair than hearing voices lifted in song. Fort Worth’s oldest black churches were located within a block or two of Ornette’s childhood homes and he recalled “all the time going from one church to the other, listening to gospel music.”8 These relatively modest buildings housed the largest meeting rooms available to the black community and appeared the more imposing for their contrast with the makeshift housing that surrounded them. Built with donations eked out of meager familial earnings, they radiated pride and accomplishment. Musician and composer John Wallace Carter (1929–1991), who attended high school with Ornette, recalled the services at Mount Gilead Baptist Church and their lasting effect on his music:

As I search my experiences now, looking for areas to call upon for thematic material, for the excitement for an out chorus, for the gutty feeling for a blues, for the beauty of a ballad, I go back often to the scenes of my early childhood. I wish I could capture the raw power of my baptizing pastor, Rev. J. L. Lenley in the out chorus on his sermon of Jesus cheating the devil out of the grave after having been entombed—the angels removing the gravestone and Jesus stepping forth in triumph. Reverend Lenley at this point always stepped off the pulpit with great drama, took the tails of his frock-tailed coat in front of him in his left hand and marched through the church, right hand fully extended, shouting at the top of his voice, “All power, good God, all power, won’t you try him today church, all power.” . . . The church would be in absolute chaos, the “amen” corner echoing, “Yas Suh, Yas suh,” and the church nurses running around from one emotionally-wrought person to another. I would sit and smile . . . beautiful music.9

The preacher-to-congregation interaction characteristic of these sermons corresponds to the practice of “call and response” present in African and other musical traditions. Preachers like Lenley could orchestrate a rhythmic back-and-forth that built to a cathartic climax. Carter, who sang in the Mount Gilead choir, described the excitement of Sunday service as “akin to the feeling of being on the stand playing jazz . . . branches of the same tree.”10

Despite the presence of these respected religious institutions, Ornette’s neighborhood, Hillside (slightly east of downtown), was considered one of Fort Worth’s least privileged. “The Southside was more wealthy territory,” Ornett...