![]()

CHAPTER ONE

OUBANGUI-CHARI

“Once upon a time there was a landlocked French colony in the very heart of Africa called Oubangui-Shari, which was best known to the outside world for supplying platter-lipped women to circus sideshows”

—Washington Post, 1977

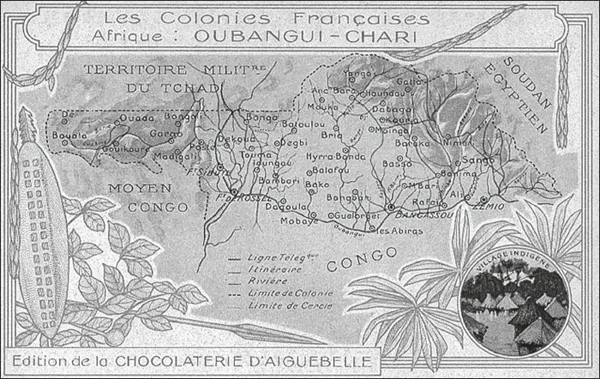

Equatorial Africa is dominated by the wide and curving sweep of the Congo river. This iconic stream drains into the vast Congo Basin from the western slopes of the Great Rift Valley, from the central plateau of southern Africa and from a northward-probing finger known as the Ubangi river. This, the largest right-bank tributary of the Congo, draws from a watershed of some 600,000 square kilometres, encompassing a significant swathe of the northern frontier of the modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo, the southern Sudanese Bahr el-Ghazal and almost the entire area of the Central African Republic.

The Central African Republic, that problem child of Francophone Africa, was known to the French during the colonial period as the Oubangui-Chari. The Ubangui river marked the southern boundary and the Chari river the northern. In between lay a vast hinterland of absolute isolation; an unmapped landscape of riverine forest, wooded hill country and woodland savannah; a beautiful Eden, remote from the main fields of interest, sparsely populated, often unpopulated, a place of manifold wildlife—gorilla and rhinoceros, crocodile and lion—shielded from civilization by tsetse fly, and far beyond the crack of the slave trader’s whip or the report of a hunter’s rifle.

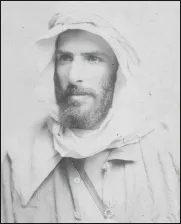

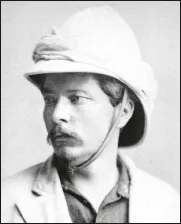

The territory was drawn into the French sphere of influence through the work of a certain Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, the Italian-born doyen of French African exploration who, through his exploration of the river systems of Gabon, claimed some quarter of equatorial Africa for France. His great rival in this enterprise was the no less prominent Welsh/American explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, who, through a series of daring escapades, staked primum petere to the Congo river itself, and by extension what hinterland he could reasonably include on behalf of the rapacious Belgian King Leopold II.

Satellite image of the Congo River Basin.

Source: Wikicommons

Map of Oubangui-Chari, from a chocolate card printed circa 1910.

Source: Wikicommons

Such were the machinations of the ‘scramble for Africa’, the global-strategic partitioning of the continent that took place toward the end of the 19th century, and which by the turn of the next had seen Africa largely assigned to one or other of the great European powers. France and Britain, of course, dominated the game, but Belgium, Germany, Portugal, Italy and Spain worked hard to establish their own variously less significant spheres of influence.

For the French, de Brazza succeeded in staking out the entire right bank of the Congo river above the Stanley Pool, securing what in due course would become known as French Equatorial Africa. This vast region was subdivided into the administrative colonies of the French Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and the enormous interior expanse of Chad. A secondary effect of this was to block further international claim to any of the territories that could be reached via the navigable Ubangui river, or Oubangui river as it was better known, and any of its tributaries. Moreover it opened the theoretical possibility that the French could use this obvious highway into the interior to probe eastward into the Sudan and the Nile valley, possibly even extending French influence as far as the Indian Ocean. In this way French imperial interest would achieve some sort of geographic rationale between French North, West and Equatorial Africa, effectively straddling the continent all the way from the Gulf of Guinea to the Horn of Africa.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.

Source: Paul Nadar

Such a scheme was enormously ambitious, but it was reflective of European imperial ambition in general, with each, to some degree or another manoeuvred to frustrate the ambitions of the other. Such was the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

In the case of what was loosely defined as Haut-Oubangui, or Upper Oubangui, the river was explored by two brothers, Albert and Michel Dolisie, who in 1890 founded the settlement of Bangui below the rapids of the same name, marking the first substantive imperial imprint in the region. The territory that they encountered conformed more or less with the catchment of the upper reaches of Oubangui river and straddled three of the major ecological zones of Africa. Along the banks of the river itself a thick belt of tropical forest replicated the enervating conditions of the Congo, while farther north, on higher ground, the forests thinned out into expansive woodland savannah before conditions of severe aridity hinted at the proximity of the Sahara desert. It was a landscape of pristine beauty, largely untouched by the intrusion of outside religion or, indeed, the depredations of the slave trade, offering fertile soils, numerous rivers, a small population and almost limitless scope for industry and development.

Henry Morton Stanley.

Source: Wikicommons

King Leopold II of Belgium.

Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand.

Source: Wikicommons

Fashoda: the governer’s house, 1906.

Source: Wikicommons

Bangui consisted of a collection of mud and grass huts in a clearing that clung tenuously to the elbow of a river bend, linked to the outside world by river traffic, and isolated in the most profound way possible in a world rapidly developing industrial communications. However, by 1906, when the territory was formalized by the arrival of a French governor, it had developed into a quiet but pleasant colonial backwater. Bangui was designed with the usual arrangement of avenues radiating from a central administrative complex, and with a sufficient number of Europeans to allow for social diversion during the languid periods between journeys downriver to the main administrative centre of Brazzaville. Here the governor-general of French Equatorial Africa managed the vast territories under his remit, including the Upper Bangui, which by 1910 was known as Oubangu-Chari.1

The indigenous population that found itself under French colonial domination numbered about a million and consisted of those groups representative of the climatic zones of the territory. The principal ethnic distinctions then, as today, are, east to west, the Banda and the Baya ethnic groups, both tending to be concentrated along the banks of the Ubangi river, and both to a greater or lesser extent owing their cultural origins to the Bantu speakers of the Niger–Congo region. The Baya, however, are the more numerous of the two, averaging some 35 per cent of the local population, and are speakers of one or other of the Ubangian languages that are more closely associated with direct regional dialects.

Among the Ubangian speakers were the M’Baka minority, a Bantu people located in the densely forested and heavily populated southwestern districts centred around the current city of Boda. The M’Baka were then, and remain today, a resolute, intelligent and resourceful sub-group within the general population and who remain, as they were then, disproportionately represented in government, business and the arts.

In the meanwhile, in 1896, a French military column left Gabon and set off inland with the objective of driving the equatorial African conquests of the Third Republic east. Specific instructions required the expedition to seize the Upper Nile in the name of France, and if possible link up with the Emperor Menelik in Abyssinia. The complement of force assigned to this expedition consisted of twelve European personnel, a detail of 150 native infantry and some 13,500 African porters. The expedition was commanded by the redoubtable Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, by then a veteran of several similar expeditions, including among them an earlier exploration of the sources of the Niger river.

After an extraordinary fourteen-month combined river and overland journey, Marchand’s expedition reached the abandoned fort of Fashoda on the Nile river, in July 1898. There, in what was widely regarded as the British sphere of influence, he hoped to rendezvous with a second French expedition that had earlier set out for the same point from Djibouti on the Red Sea. Unfortunately this expedition had already arrived in Fashoda and, finding no trace of Marchand, had made the assumption that he had either perished or returned, and thus it had itself turned around.

The British, of course, were aware of all of this, even contemplating at one time the dispatch of a military expedition from Uganda to intervene. However, it was fortunate at that moment that Lord Kitchener, in command of an Anglo–Egyptian army fresh from victory at Omdurman, was available locally to respond. On 11 September 1898, Kitchener arrived at Fashoda on board a flotilla of five steamers carrying two battalions of Sudanese, one hundred Cameron Highlanders, a battery of artillery and four Maxim guns.

This immediately precipitated an international crisis. France, it seemed, was prepared to back the legitimacy of the expedition to the point of war with Britain. Kitchener, however, and in a manner somewhat out of character, dealt with the matter sympathetically and cautiously, recognizing no doubt in Marchand a man of character and determination who was caught somewhat on the horns of a dilemma. It was soon agreed between the two that matters on the ground could best remain static with the issue left to the metropolitan powers to resolve. Kitchener, therefore, established a garrison alongside the French, hoisted the Egyptian flag (avoiding any inflammatory temptation to hoist the Union Jack) and shortly after left the scene.

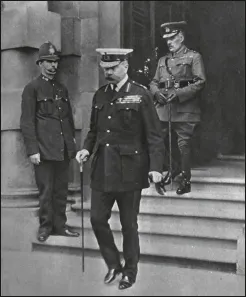

The last picture of Lord Kitchener, seen here leaving Westminster from a meeting with MPs.

Source: Illustrated London News

The Battle of Omdurman.

Source: Wikicommons

Meanwhile, in Europe a diplomatic war was being fought between London and Paris with the usual jingoistic verbiage of the times flowing back and forth across the English Channel. That British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury should have applied such thoroughly British understatement as to describe Marchand as “an explorer in difficulties on the Upper Nile” incensed the French, who replied that this was simply another instance of British greed and bul...