- 72 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"[An] informative and readable account of the growth of the politically motivated and extremely violent Mau Mau in Kenya." —

Military Historical Society

The Second World War forever altered the complexion of the British Empire. From Cyprus to Malaya, from Borneo to Suez, the dominoes began to fall within a decade of peace in Europe. Africa in the late 1940s and 1950s was energized by the grant of independence to India, and the emergence of a credible indigenous intellectual and political caste that was poised to inherit control from the waning European imperial powers.

In Kenya, however, matters were different. A vociferous local settler lobby had accrued significant economic and political authority under a local legislature, coupled with the fact that much familial pressure could be brought to bear in Whitehall by British settlers of wealth and influence, most of whom were utterly irreconciled to the notion of any kind of political hand over. Mau Mau was less than a liberation movement, but much more than a mere civil disturbance.

This book covers the emergence and growth of Mau Mau, and the strategies applied by the British to confront and nullify what was in reality a tactically inexpert, but nonetheless powerfully symbolic black expression of political violence. That Mau Mau set the tone for Kenyan independence somewhat blurred the clean line of victory and defeat. The revolt was suppressed and peace restored, but events in the colony were nevertheless swept along by the greater movement of Africa toward independences, resulting in the eventual establishment of majority rule in Kenya in 1964.

The Second World War forever altered the complexion of the British Empire. From Cyprus to Malaya, from Borneo to Suez, the dominoes began to fall within a decade of peace in Europe. Africa in the late 1940s and 1950s was energized by the grant of independence to India, and the emergence of a credible indigenous intellectual and political caste that was poised to inherit control from the waning European imperial powers.

In Kenya, however, matters were different. A vociferous local settler lobby had accrued significant economic and political authority under a local legislature, coupled with the fact that much familial pressure could be brought to bear in Whitehall by British settlers of wealth and influence, most of whom were utterly irreconciled to the notion of any kind of political hand over. Mau Mau was less than a liberation movement, but much more than a mere civil disturbance.

This book covers the emergence and growth of Mau Mau, and the strategies applied by the British to confront and nullify what was in reality a tactically inexpert, but nonetheless powerfully symbolic black expression of political violence. That Mau Mau set the tone for Kenyan independence somewhat blurred the clean line of victory and defeat. The revolt was suppressed and peace restored, but events in the colony were nevertheless swept along by the greater movement of Africa toward independences, resulting in the eventual establishment of majority rule in Kenya in 1964.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mau Mau by Peter Baxter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE:

IN SUPPORT OF THE CIVIL AUTHORITY

“The mood and temper of the public with regards to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilisation of any country”

—Winston Churchill, Commons debate

—Winston Churchill, Commons debate

The Mau Mau Rebellion never achieved the status of a war, civil or otherwise, and was dealt with almost entirely through the application of common law. Emergency regulations provided for the use and aid of the military without usurping overall civilian authority in the containment of the crisis. Therefore, arguably, the most potent and widely applied weapon in the British arsenal was the gallows. Those acts of violence identifiable as being politically motivated, or perpetrated in the furtherance of a military goal, were dealt with through the court system using criminal law with the application thereafter of criminal punishment. No accommodation was made to modern conventions of warfare and no captives afforded the status of prisoner of war. It might be added that many among the settler community saw this as fair and proper treatment for criminals, bearing in mind their refusal to grant the rebellion any status other than criminal, and bearing in mind also that the level of violence perpetrated by Mau Mau, and the manner in which so many victims were killed, exceeded any modern convention of wartime behaviour.3

Military units were only entitled to open fire without challenge in areas of forest or mountain known to be uninhabited. These were in due course classified as Prohibited Areas and came to include most of the Aberdare and Mount Kenya forest reserves and surrounding areas, which accounted for the main areas of refuge for active Mau Mau gangs. The Prohibited Area also included a strip several hundred metres wide on the leading edges of both the Aberdare and Mount Kenya forests, each of which were secured by police posts, army camps and patrols. Men captured or detained anywhere within or around these areas were delivered immediately to the police who would seek a conviction based on a transgression of the colony’s law. Trials were arbitrated by magistrates with Supreme Court powers, acting under emergency regulations, hearing cases arising from arson, oath administration, murder and assault. In due course, emergency assize courts were introduced, along with the removal of a preliminary hearing prior to appearance before the Supreme Court, in order to deal with the mounting backlog of trials.

An interesting anecdote recorded by Military Intelligence Officer Frank Kitson, in his memoir Gangs and Counter Gangs, gives some insight into how difficult and confusing it could be to operate under these conditions:

One evening Eric Holyoak contacted a small gang, killing one member of it and capturing two others, one of whom had a rifle. The police charged him with being an armed terrorist, the other was charged with consorting. The defence case for the first man was that he had recently been captured by the gang and had been forced to carry the weapon so as to compromise himself. The judge accepted that view and the man was acquitted. Now if this man was not an armed terrorist, then the other could not have been consorting with an armed terrorist, so he was acquitted too. All this may have been good law but made little sense to Eric who in addition to the action had also spent some time hanging around in Nairobi waiting to give evidence.12

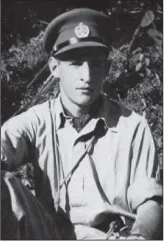

Frank Kitson, who pioneered the ‘pseudo’ concept.

Detention orders were another key element of emergency regulations, allowing for the mass imprisonment of many thousands of Kikuyu for both preventative and screening purposes. The single greatest frustration felt by security forces was their inability to determine from outward appearances the political loyalties of a uniform black population. In this regard intelligence played a key role from the onset. Pivotal would be the hearts and minds concept, introduced into the counter-insurgency lexicon by General Sir Gerald Templar, High Commissioner for Malaya, who commented on the question thus: “… the answer lies not in pouring more troops into the jungle, but rests in the hearts and minds of the people. Winning ‘hearts and minds’ requires understanding the local culture.”13

A constable savagely hacked to death by Mau Mau in the charge office of Naivasha police station, 26 March 1952.

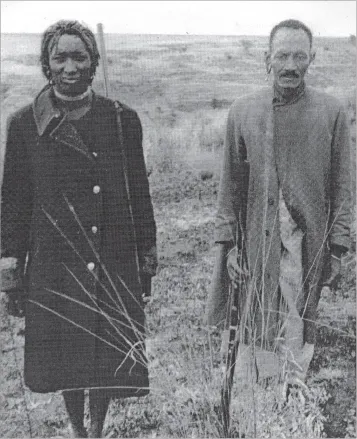

Masai tribesmen recruited by settlers as farm guards. Issued with a shotgun and an old greatcoat they patrolled cattle bomas, wheat stores and squatter labour lines.

In fact, during the early stages black commitment to the rebellion was almost absolute, with the only exception being a conservative minority of Kikuyu society: those aligned to the government either through appointment as chiefs or through work in the civil services, and those among the Kikuyu who had, through the machinations of land tenure as defined by colonial law, managed to gain land and influence, and who saw no merit in adjusting the status quo. Of these a good many met their ends at the sharp end of a simi, or through arson. It was the responsibility of the intelligence community, and most specifically the police Special Branch, to cut through the wall of silence in order to create a three-dimensional picture of the rebellion.

Police Special Branch had from the onset given the administration repeated warnings that trouble was brewing. That nothing at the time was done is more reflective of the Governor’s unwillingness to confront reality than any failings in the normal civil early-warning system. This intelligence tripwire, as was typically the case throughout British Africa, had its roots in provincial and district administration and law enforcement, and reached through a network of local informers right down to the grassroots village level.

The local intelligence community, however, was at the time small and ill equipped for the sudden demands of a full-scale insurrection. In November 1952, and again in April 1953, the head of MI5, the British internal intelligence and security organisation, visited Kenya in order to advise on and facilitate the expansion of the colony’s security services. Organisational changes included the appointment of a British Security Service official as intelligence adviser to the colonial government along with the rapid expansion in manpower and funding of Special Branch. For specific military intelligence – that which was concerned with combat operations – the post of Senior Intelligence Staff Officer was established at GHQ, with a staff initially made up of plain-clothed police officers deployed in each of the affected areas. In due course these were supplemented by Field Intelligence Assistants drawn from senior NCOs of the Kenya Regiment, all of whom would have been local whites.

In mid-1953, the system was bolstered by the addition of two District Military Intelligence Officers in a supervisory role, both of whom were regular British Army officers. One of these was Captain Frank Kitson who would in due course achieve wide recognition for his work with pseudo groups and the operational use of turned guerrillas.

By the end of 1953, the local intelligence community could confidently claim to have constructed a reasonably accurate picture of the overall organisation and the leading personalities of Mau Mau. This picture came into even sharper focus with the capture on 15 January 1954 of Waruhiu Itote, or General China, one of the original and most influential of the Mau Mau leaders. This event would in fact have a profound effect on the general intelligence picture of Mau Mau, and the military and police special operations tactics that would rapidly begin to evolve to destroy it.

Of the role of the Kenya Police during the Mau Mau Rebellion much has been written, and a general consensus has been reached that the conduct of this force, alongside the Kenya Police Reserve and the Kenya Regiment, left much to be desired. Most of the many reported instances of abuse or mistreatment of captured Mau Mau, suspected Mau Mau or local Kikuyu tribesmen suspected of Mau Mau sympathies, were traceable in one way or another to members of these three units. The anecdotal record in this regard is huge, the official record somewhat smaller, but the fact that a substrata of abusive, vengeful and at times homicidal personnel existed within the Kenya Police and Police Reserve has never been disputed. A British conscript serving with the Devons & Buffs commented during an interview conducted much later: “The Police just treated the prisoners like animals. As soon as you handed them over the kicks and slaps began. Goodness knows what they did to the poor buggers when they got them behind closed doors.”14

Mau Mau historian, Robert B. Edgerton, in his book Mau Mau, An African Crucible, quotes an anonymous interview dated 1962 with a member of the Kenya Police Reserve in reference to the treatment of Mau Mau suspects. Sections of this bear quoting in full:

… while we were waiting for the sub-inspector to come back I decided to question the Mickeys.4 They wouldn’t say a thing, of course, and one of them, a coal-black bastard, kept grinning at me, real insolent. I slapped him hard, but he kept on grinning at me, so I kicked him in the balls as hard as I could. He went down in a heap but when he finally got up on his feet he grinned at me again, and I snapped, I really did. I stuck my revolver right in his grinning mouth … and I pulled the trigger. His brains went all over the side of the Police Station. The other two Mickeys were standing there looking blank. I said to them that if they didn’t tell me where to find the rest of the gang I’d kill them too. They didn’t say a word so I shot them both. When the sub-inspector drove up, I told him that the Mickeys tried to escape. He didn’t believe me but all he said was “bury them and see the wall is cleaned up”.15

The Kenya Police Reserve and the Kenya Regiment were manned by the compulsory conscription of white males in the colony mandated by the National Service Act, gazetted by the local Legislative Council in 1943. In the matter of human rights abuses, a distinction has been clearly drawn between personnel recruited directly from Britain to augment local police enrolment and those drawn from within the colony for territorial service with either the Kenya Police Reserve or the Kenya Regiment. Conscripted British troops brought in from the outside alongside short contract British police recruits were not so directly vested in the outcome of the rebellion, as were local whites whose commercial and agricultural interests, not to mention matters of personal security, were directly on the line.

This, however, can only be viewed as part of the explanation. The wider conclusion might perhaps have more to do with the moral condition of the white settler community in general. Anecdotal reference to this has been made in frequent accounts of the period, and although it can hardly be defined in terms of specifics, some light can be shed on the matter by the attitudes and observances of those on the outside looking in. One of the most reliable of these must be General Sir George Erskine, of whom much will be heard later, who arrived in the colony in 1953 as GOC-in-Chief of East Africa Command, and who, in frequent letters to his wife, derided the white settler community as being in the main dishonest, racist, violent and undeserving of either the general race-superiority that they awarded themselves or the responsibility to govern.

It must also be reiterated that the conduct of the Kenya Emergency, for all intents and purposes a civil war, was undertaken at all times within the limitations of common law. Subject to these limitations was British Intelligence Officer Frank Kitson:

And so it came about that, once in a way, somebody would take the law into his own hands and strike a blow where one seemed necessary, because the existing legal methods of dealing with the situation were not good enough. Looking back, I am sure that this was wrong. Certainly this sort of conduct saved countless loyalist lives and shortened the Emergency. All the same it was wrong because the good name of Britain was being lost for the sake of saving a few thousand Africans and a few million pounds of the taxpayers’ money. Regardless of their popularity, the leaders of the Government and Security Forces stood four square against such practices, which were anyhow very rare.16

Kitson clearly glosses over some of the grosser aspects of mistreatment meted out to Mau Mau suspects, and those detained on active operations, but he also speaks for the obvious frustrations of those trying to do a very difficult job under highly restrictive political conditions. Kitson also observes, quite accurately, that it was not beyond Mau Mau, and Mau Mau supporters within and without the colony, to generate a maximum of effect from these instances, as the many detractors of the organisation did in regards to moments of extreme Mau Mau brutality.

There were also, of course, daily instances of bending the rules. A particular incident recorded by Frank Kitson involved a Kenyan-born Field Intelligence Officer who was building a new operations camp with neither funds nor labour. A raid was therefore contrived on a nearby settlement during a Sunday beer drink, and while a large number of men waited in the camp yard for their papers to be processed, something that could be expected to take all day, the men were put to work building and thatching huts.

General Sir George Erskine, Commander-in-Chief East Africa 1953–59, touring a settler farmer’s shamba on the Kinangop plateau. Note the pistol slung from the lady’s waist.

White children pose in front of their farmstead, typically fortified with barbed wire and sandbags.

Another shrewd use of black expertise and labour was in the formation of the Home Guard, or the Kikuyu Guard, one of the most divisive and yet productive pillars of the British counter-insurgency response. The movement was begun by the Christian missions and senior Christian chiefs of Kikuyuland as protection from attacks mounted against the loyal population by Mau Mau. Loose vigilante and resistance groups began to be formed during the course of 1951, but were not banded together as an organised militia until the suggestion was mooted at an official level sometime towards the end of 1952. The principal motivation for the government in this regard was political: the use of a Kikuyu militia to confront a Kikuyu rebellion would smudge the hitherto clear lines of race conflict, and present the crisis as a black-on-black affair and less as a movement seeking the removal of white minority rule. The official adoption and organisation of a Kikuyu defence system, the Kikuyu Guard, in actual fact set the stage for what could hardly have been less than a civil war. However, it was an astute move, without doubt, and very much in keeping with the divide-and-rule tactics applied els...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Glossary and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: In Support of the Civil Authority

- Chapter 2: The Land Freedom Armies

- Chapter 3: Paradise Lost

- Chapter 4: The Blunt Instrument

- Chapter 5: The Long Goodbye

- Chapter 6: Special Forces

- Chapter 7: The Hunt for Dedan Kimathi

- Chapter 8: Rehabilitation

- Chapter 9: Legacy of Mau Mau

- Appendix: British Units involved in the Kenyan Emergency

- Notes

- Helion Books