![]()

Chapter 1

Historical Background: Alliances and Conflicts

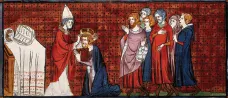

Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne as emperor on Christmas Day 800; from Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, fourteenth century

Following the collapse of the western portion of the Roman Empire at the end of the fifth century, the Italian peninsula was attacked by waves of invaders. To preserve their independence, regions established themselves as duchies, republics, principalities and kingdoms.

In the late eighth century, the papacy forged alliances with Frankish kings to defend territories that they claimed from the time of the emperor Constantine three centuries earlier. On Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor of the Romans in St Peter’s Square. The coronation marked the beginning of an era lasting several centuries when the popes and Holy Roman Emperors entered into alliances or abandoned each other according to the politics of the day.

Conflict arose over the selection of bishops and land. Bishops were not simply spiritual governors of dioceses; some were also wealthy landowners, receiving a tithe on the produce of those who worked on their lands. They may not have owned the properties themselves, but as long as they held office they enjoyed the abundant benefices. Properties were held for the good of the diocese but numerous bishops used their position to aggrandise their families and lived more like secular princes. From the end of the eleventh century, many families allied themselves to the emperor or the local bishop.

Life in the Middle Ages was feudal, based on a system where each person knew their rank in the social order. The average life expectancy was about forty years, and infant mortality was high. The aristocracy owed their hereditary titles to the emperor. Vassals, or citizens, received land from the lord in exchange for work and taxes. In times of war, the lord or king raised armies from the young men within his territories.

In the latter half of the eleventh century, a dispute broke out between pope and emperor. The latter sought control over ecclesiastical properties in his territories, particularly the high offices that he wanted to grant to his political supporters. The popes saw this as an unwarranted abrogation of their spiritual authority.

In Italy those belonging to the faction loyal to the papacy were called Guelphs, an Italianisation of the German Welfs, dukes of Bavaria. Those who owed loyalty only to the emperor were known as Ghibillines, a corruption of Waiblingen, the German town where the faction originated. Various cities and duchies espoused one or other faction, regularly employing mercenary soldiers to augment their urban armies and go to war. The rivalry lasted into the middle of the sixteenth century when new invaders united them against a common enemy.

The city of Urbino had long owed allegiance to the imperial faction. The ruling da Montefeltro family, which dated from the twelfth century, had regularly shifted support from the papacy to the emperor according to political necessity.

In 1403, Guidoantonio da Montefeltro inherited extensive lands from his father and further expanded his family holdings. The young Guidoantonio, a condottiere (mercenary soldier), wove his way between the papal and imperial factions, siding with one and then unexpectedly switching allegiance for the benefit of his family.

When he died on 21 February 1443, Guidoantonio was succeeded by his son, Oddantonio. The sixteen-year-old had little interest in politics and lacked experience in the cut-throat business of ruling. In April of that year, Pope Eugenius IV made him the first Duke of Urbino as a token of his gratitude for the family’s help in fighting the Sforza dynasty of Milan.

Oddantonio’s lack of application to the affairs of state gained him a gallery of enemies. During the night of 21 July 1444 conspirators gained access to the private chambers of the new duke, who had retired after a lengthy feast. Along with some loyal bodyguards, Oddantonio was stabbed to death. His corpse was thrown on the floor and the unidentified assassins slipped away.

Contemporaries speculated that Federico, Oddantonio’s half-brother, may have been implicated in the murder. Born out of wedlock in 1422, Federico was the son of Guidoantonio and Elisabetta degli Accomandugi. The young Federico was legitimised when his father convinced his wife, Caterina Colonna, a niece of Pope Martin V, to persuade the pope to acknowledge the boy as Guidoantonio’s heir. The pope agreed, and in a letter dated 20 December 1424, Martin decreed that the two-year-old Federico would become Guidoantonio’s heir, on the condition that if a legitimate son were to be born, Federico would forfeit his right of inheritance.

On 25 July 1425, a son, Raffaello, was born to the couple, but the infant died within a few hours. Two years later, on 18 January 1427, Caterina Colonna gave birth to another son, who was baptised Oddantonio. Three daughters were born subsequently, but Guidoantonio was satisfied that in Oddantonio, he now had an heir to carry on the family line. He kept Federico away from the court so as not to provoke an eventual challenge to the succession.

At the age of sixteen, Federico became a condottiere and was apprenticed to Niccolo Piccinino, one of the most brutal and successful mercenary commanders in northern Italy. Already a gifted horseman and strategist, Federico honed his skill with the sword and bow, taking part in several successful sieges and skirmishes in the region. Federico gained an introduction to Francesco I Sforza of Milan, to whom he successfully offered his services.

The accession of Federico to the lordship of Urbino in 1444 secured the town’s fortunes over the next two decades. Federico’s military skills brought him lucrative contracts and he quickly amassed a considerable fortune. He skilfully forged alliances with the neighbouring families, to whom he offered his services and protection. His prudent and successful administration of Urbino attracted the attention of neighbours who wanted his lands.

Of all Federico da Montefeltro’s foes, none was more constant than Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini, which lay to the north of Urbino. The two men, although rivals, were alike in their military prowess and devotion to the arts. Both were unscrupulous in selling their military services to whoever would pay the highest fee. As each campaign was successfully waged and won, the families expanded their holdings.

In 1450, Federico welcomed his father-in-law, Francesco Sforza, who had just become Duke of Milan. During a joust, Federico was hit by a lance which tipped open his visor. As a result of the accident, Federico lost the sight in his right eye and suffered severe damage to the bridge of his nose. He henceforth insisted that artists portray only his left profile, to hide the unsightly scars.

In 1462, Federico was appointed to the titular and ceremonial role of gonfaloniere, or flagbearer, of the Holy Roman Church by Pope Callistus III, the first Borgia pope. The honorific title was reconfirmed by the humanist Pope Pius II and again by his successor, the della Rovere Pope Sixtus IV, who allied the da Montefeltro family to his own.

In the spring of 1474, three years after his election as pope, Sixtus IV granted Federico da Montefeltro the title Duke of Urbino. The gonfaloniere had fought against the Umbrian towns of Todi and Spoleto with troops led by Giuliano della Rovere, the pope’s nephew. In a shrewd political move, Federico offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to Giuliano’s brother, Giovanni, who was named lord of Senigallia and Mondovì. The della Rovere and da Montefeltro families were now entwined in a dynasty to the mutual benefit of both. In an era of shifting alliances, the papacy came to rely on military force to defend its territories, which lay in a swathe across the Italian peninsula, from encroachments by local landowners who unscrupulously invaded any neighbouring territories whenever the opportunity arose.

Avignon: The ‘Babylonian Captivity’

From 1309 to 1376 seven popes had chosen to live in the French town of Avignon. Following the death of Pope Benedict XI in July 1304, fifteen cardinals gathered in Perugia to elect his successor. After eleven months of inconclusive balloting, during which rations were gradually reduced to bread and water, ten of the cardinals succeeded in breaking a pro-French/anti-French deadlock and elected Raymond Bertrant de Got, the archbishop of Bordeaux.

De Got was not a cardinal and was not present at the conclave, so a delegation was dispatched to France to request that he accept the papal nomination. De Got agreed, taking the name Clement V. He refused to travel to Rome, fearing the quarrelling noble families, and chose to be crowned in Lyons. On the advice of the French king, Philip the Fair, Clement took up residence in Avignon, on the left bank of the Rhône river, and the next six popes, all French, opted to remain in the comparative seclusion and safety of the small French town.

When Gregory XI visited Rome in 1377, his intention was to re-establish the papal court in the Eternal City. But his sudden death a year later led to a schism that lasted until Cardinal Oddone Colonna was elected Martin V by the Council of Constance in 1417.

The Duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro and son

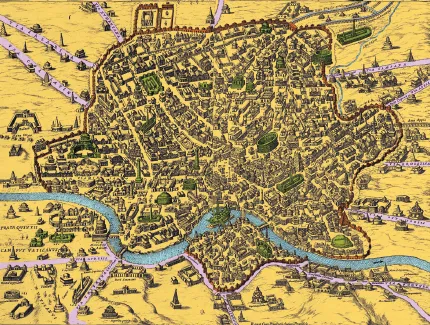

A map of Rome engraved by Giacomo Lauro (1550–1605) in the sixteenth century

The Papacy Returns to Rome

When Martin entered the city in 1420, he found it in a sorry state. The Cathedral of St John had been burned to the ground some thirty years earlier and the roof of the adjacent Lateran palace on the Caelian hill had fallen in. As the papal cavalcade wound its way through the narrow, dank streets, the people turned out to give a jubilant welcome to the new pope who had been born in Genazzano, some forty miles east of Rome. Few understood the complex reasoning behind the election of a member of the aristocratic Colonna family, and most simply wished for the papacy to settle once more in the Eternal City. The century-long absence of the papacy from Rome had diminished Rome economically and the inhabitants knew that the pope held the key to renewed prosperity.

Martin initially settled the papal court at the Basilica of the Holy Apostles beside his family residence close to the ruins of the R...