![]()

Part One

The Austen Connection

![]()

Chapter 1

Jane/Anne

Readers of Jane Austen’s novels love her work partly because of the great emotional power with which she expresses love, most notably in her last novel Persuasion (1818). In that novel, Anne Elliot’s and Captain Wentworth’s love for each other has survived years of separation and family opposition, and their reunion, the climax of the novel, is probably the most satisfying in English fiction.

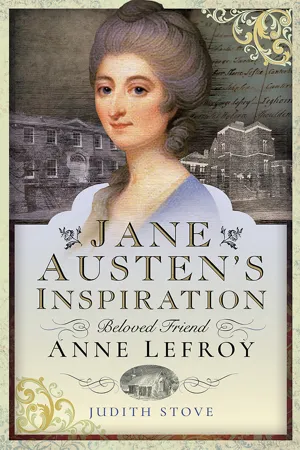

Yet the most emotional work of Jane Austen in her own voice was not to be found in her surviving letters. It is her 1808 poem in memory of her friend, Anne Brydges Lefroy, who had died four years earlier, after falling from a horse. Few commentators have thought it worthwhile to discuss the poem; fewer still to consider in detail what it suggests about the nature of the relationship between the two women over more than fifteen years (from the late 1780s until Anne’s death in 1804).

Anne Lefroy was much older than Jane Austen; she was aged about 40 when Jane was in her teens. When Jane was 20, she met and seems to have fallen in love with Anne’s husband’s nephew, Tom Lefroy. Did Anne Lefroy play the part of a Lady Russell from Persuasion, in encouraging the young man and young woman to separate because of worldly considerations? Did Jane’s dear friend bring sadness into her life?

First, it is important to look at Jane Austen’s records of the events. Tom Lefroy is mentioned in the very first letter of Jane Austen’s which survives, that of 9-10 January 1796. Jane was just 20 years old, and this is the letter in which she tells her sister Cassandra about the young man with whom she has been spending time over Christmas 1795: Tom Lefroy.

Thomas-Langlois Lefroy (1776–1869) was the son of George Lefroy’s brother, Anthony-Peter (1742–1819). Anthony rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the British Army, and lived in Ireland. He married Anne Gardiner and had eleven children, of whom Tom was the sixth, coming after five daughters.1

Tom’s full name is clearly a respectful nod to Anthony’s Langlois uncles, most significantly Benjamin, who wielded considerable influence within the clan. Tom came from Dublin to Ashe to visit his uncle George and family, before undertaking law studies at Lincoln’s Inn in London.2

Tom’s subsequent career in the law was to be stellar, but there is evidence that his academic performance had already been impressive. At Trinity College, Dublin, which he had entered at the age of 14: ‘Every academic honour, premiums, certificates, a moderatorship, and finally, in 1795, the gold medal of his class, attended his progress.’3

In a very famous passage, Jane tells Cassandra that she and Tom showed disregard for the conventions by sitting out dances together:

Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together.4

Their growing friendship had apparently been noticed, and not necessarily in a good way. Jane goes on:

He is so excessively laughed at about me at Ashe, that he is ashamed of coming to Steventon, and ran away when we called on Mrs Lefroy a few days ago.

Jane seems here to be trying to dismiss her evident feelings for Tom. Some encouragement occurred while she was still writing the same letter:

After I had written the above, we received a visit from Mr Tom Lefroy and his cousin George. The latter is really very well-behaved now; and as for the other, he has but one fault, which time, will, I trust, entirely remove – it is that his morning coat is a great deal too light. He is a very great admirer of Tom Jones, and therefore wears the same coloured clothes, I imagine, which he did when he was wounded.5

Jane and Cassandra seem, at an earlier stage, to have agreed that George Lefroy junior was badly behaved (although probably he was simply cheeky, in the manner of pre-teen boys).

In her notes to this letter, Deirdre Le Faye cites the passage from Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, to which Jane Austen refers:

As soon as the sergeant was departed, Jones rose from his bed, and dressed himself entirely, putting on even his coat, which, as its colour was white, showed very visibly the streams of blood which had flowed down it.6

Tom Jones’ injury had been caused by a bottle thrown at his head during a rowdy encounter in the army mess, when Tom thought that the name of his beloved, Sophia Western, had been uttered disrespectfully. It was a mock-heroic setting, with the injury not incurred in battle, but as a result of Tom’s heightened, and naïve, sense of honour. For Jane Austen to have thought of the scene indicates her feelings of interest, affection and honour for the other Tom, Tom Lefroy, but also her keen sense of the mock-heroic.

It would appear that even before this, Cassandra had already offered some kind of warning to her sister about becoming a public spectacle in her flirtation with Tom.7 Jane had written: ‘You scold me so much in the nice long letter which I have this moment received from you, that I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved…’8

It is significant that a letter from Jane to Cassandra is missing after this one, dated 12 or 13 January 1796.9 It is safe to infer, as Jon Spence did, that Cassandra destroyed letters relating to this time.10 Jane expected it to become more than a flirtation. In her next (her second) surviving letter, she writes:

Our party to Ashe tomorrow night will consist of [cousin] Edward Cooper, James (for a Ball is nothing without him), Buller, who is now staying with us, & I – I look forward with great impatience to it, as I rather expect to receive an offer from my friend in the course of the evening. I shall refuse him, however, unless he promises to give away his white Coat.11

Yet how serious was Jane Austen, here? Her context, as usual, is satirical. She manages to include a shot at her widowed brother James, who was not in general the most affable of men, but who at this time was passing through a phase of extreme sociability, no doubt with a view to attracting a second wife.

‘Buller’ was the Reverend Richard Buller (1776–1806), who had been a pupil of the Reverend George Austen at Steventon, and was of an age to be thought, other things being equal, to have a possible interest in Jane. Yet other things were not equal. Jane’s partiality for Tom Lefroy over any other potential admirer was highly visible.

Tell Mary [Lloyd, soon to become that second wife of James Austen] that I make over Mr Heartley & all his Estate to her for her sole use and Benefit in future, & not only him, but all my other Admirers into the bargain wherever she can find them, even the kiss which C[harles] Powlett wanted to give me, as I mean to confine myself in future to Mr Tom Lefroy, for whom I donot [sic] care sixpence. Assure her also as a last & indubitable proof of Warren’s indifference to me, that he actually drew that Gentleman’s picture for me, & delivered it to me without a Sigh.12

Here Austen, mimicking the style of a will and testament, names no fewer than three other possible admirers: Mr Heartley; Charles Powlett; and ‘Warren’. Deirdre Le Faye, the world authority on Jane Austen’s letters, has been unable to identify Mr Heartley except as ‘Possibly a member of the Hartley family, of Bucklebury, Berks.’13

Charles Powlett is identified by Deirdre Le Faye as a child of Percy Powlett, one of the illegitimate sons of the third Duke of Bolton, also Charles Powlett or Paulet (1685–1754). The Bolton family lived at Hackwood Park, near Ashe, and later family members became friends of the Lefroys.

The number of Charles Powletts in the extended family is certainly confusing. This Charles (b.c. 1765–1834) was brought up at Hackwood Park by his uncle, also Charles (1728–1809). He failed to graduate, but still took orders and held several Bolton family livings. At the time of Jane Austen’s early letters, this Charles Powlett was rector of Itchenstoke, Hampshire, some fourteen miles from Ashe.14

On the other hand, at this time Lord Bolton (Thomas Orde-Powlett) and Lady Bolton had a young son, inevitably called Charles Powlett, born in the second half of the 1780s, who would have been old enough to demand a kiss from Jane Austen in 1796.15 Whichever the Charles Powlett to whom 20-year-old Jane refers – the one ten years older than herself, or the one six or seven years younger – both are clearly joke-worthy.

This leaves Mr Warren. This man has been identified by Deirdre Le Faye as John-Willing Warren (1771–c.1831). He had probably been a pupil of the Reverend George Austen at Steventon, then was a friend of James Austen at Oxford, contributing to James and Henry Austen’s magazine The Loiterer.16 Jane Austen’s familiar use of his surname, as with ‘Buller’, indicates a long-term family friendship; it was a way in which women mimicked male address to each other, reserved for very close friends (we note that in Emma, the heroine resents Mrs Elton referring to the master of Donwell Abbey as ‘Knightley’). John Warren must have been attached to Jane Austen to draw for her a picture of Tom Lefroy.

Jane concludes this letter with a hopeful note:

Friday. At length the Day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy, & when you receive this it will be over. – My tears flow as I write, at the melancholy idea.17

As we know, no offer came from Tom Lefroy, either at that meeting, or subsequently. The next surviving letter is from London, address simply given as ‘Cork Street’. The only Austen connection known at Cork Street was Benjamin Langlois, the Reverend George Lefroy’s uncle, so it has been reasonably conjectured that the Austens were staying with him.18

However, a great deal more has been made of this than simply their acquaintance through the Lefroys. Jon Spence thought it ‘unusual’ that the Austens would be staying with Benjamin Langlois.19 Spence thought that it indicated a special relationship between Jane and Tom, possibly fostered by Anne:

Perhaps [Anne] herself felt betrayed, especially if she had had a hand in arranging the meeting in Cork Street.20

Yet we do not know even if Jane Austen met Tom at Cork Street. The invitation could have been simply from Benjamin Langlois to honoured friends of his nephew the Rector of Ashe, and Tom may not have been there at the time. Jane Austen’s letter does not indicate that he was. She opens with a typically funny declaration, but we are not to take it as suggesting anything about actual sexual conduct.