- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A revolutionary new understanding of the human brain and its changeable nature.

The brain is a dynamic, electric, living forest. It is not rigidly fixed but instead constantly modifies its patterns – adjusting to remember, adapting to new conditions, building expertise. Your neural networks are not hardwired but livewired, reconfiguring their circuitry every moment of your life.

Covering decades of research – from synaesthesia to dreaming to the creation of new senses – and groundbreaking discoveries from Eagleman's own laboratory, Livewired surfs the leading edge of science to explore the most advanced technology ever discovered.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Livewired by David Eagleman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Popular Culture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE ELECTRIC LIVING FABRIC

Imagine this: instead of sending a four-hundred-pound rover vehicle to Mars, we merely shoot over to the planet a single sphere, one that can fit on the end of a pin. Using energy from sources around it, the sphere divides itself into a diversified army of similar spheres. The spheres hang on to each other and sprout features: wheels, lenses, temperature sensors, and a full internal guidance system. You’d be gobsmacked to watch such a system discharge itself.

But you only need to go to any nursery to see this unpacking in action. You’ll see wailing babies who began as a single, microscopic, fertilized egg and are now in the process of emancipating themselves into enormous humans, replete with photon detectors, multi-jointed appendages, pressure sensors, blood pumps, and machinery for metabolizing power from all around them.

But this isn’t even the best part about humans; there’s something more astonishing. Our machinery isn’t fully preprogrammed, but instead shapes itself by interacting with the world. As we grow, we constantly rewrite our brain’s circuitry to tackle challenges, leverage opportunities, and understand the social structures around us.

Our species has successfully taken over every corner of the globe because we represent the highest expression of a trick that Mother Nature discovered: don’t entirely pre-script the brain; instead, just set it up with the basic building blocks and get it into the world. The bawling baby eventually stops crying, looks around, and absorbs the world around it. It molds itself to the surroundings. It soaks up everything from local language to broader culture to global politics. It carries forward the beliefs and biases of those who raise it. Every fond memory it possesses, every lesson it learns, every drop of information it drinks—all these fashion its circuits to develop something that was never preplanned, but instead reflects the world around it.

This book will show how our brains incessantly reconfigure their own wiring, and what that means for our lives and our futures. Along the way, we’ll find our story illuminated by many questions: Why did people in the 1980s (and only in the 1980s) see book pages as slightly red? Why is the world’s best archer armless? Why do we dream each night, and what does that have to do with the rotation of the planet? What does drug withdrawal have in common with a broken heart? Why is the enemy of memory not time but other memories? How can a blind person learn to see with her tongue or a deaf person learn to hear with his skin? Might we someday be able to read the rough details of someone’s life from the microscopic structure etched in their forest of brain cells?

THE CHILD WITH HALF A BRAIN

While Valerie S. was getting ready for work, her three-year-old son, Matthew, collapsed on the floor.1 He was unarousable. His lips turned blue.

Valerie called her husband in a panic. “Why are you calling me?” he bellowed. “Call the doctor!”

A trip to the emergency room was followed by a long aftermath of appointments. The pediatrician recommended Matthew have his heart checked. The cardiologist outfitted him with a heart monitor, which Matthew kept unplugging. All the visits surfaced nothing in particular. The scare was a one-off event.

Or so they thought. A month later, while he was eating, Matthew’s face took on a strange expression. His eyes became intense, his right arm stiffened and straightened up above his head, and he remained unresponsive for about a minute. Again Valerie rushed him to the doctors; again there was no clear diagnosis.

Then it happened again the next day.

A neurologist hooked up Matthew with a cap of electrodes to measure his brain activity, and that’s when he found the telltale signs of epilepsy. Matthew was put on seizure medications.

The medications helped, but not for long. Soon Matthew was having a series of intractable seizures, separated from one another first by an hour, then by forty-five minutes, then by thirty minutes—like the shortening durations between a woman’s contractions during labor. After a time he was suffering a seizure every two minutes. Valerie and her husband, Jim, hurried Matthew to the hospital each time such a series began, and he’d be housed there for days to weeks. After several stints of this routine, they would wait until his “contractions” had reached the twenty-minute mark and then call ahead to the hospital, climb in the car, and get Matthew something to eat at McDonald’s on the way there.

Matthew, meanwhile, labored to enjoy life between seizures.

The family checked into the hospital ten times each year. This routine continued for three years. Valerie and Jim began to mourn the loss of their healthy child—not because he was going to die, but because he was no longer going to live a normal life. They went through anger and denial. Their normal changed. Finally, during a three-week hospital stay, the neurologists had to allow that this problem was bigger than they knew how to handle at the local hospital.

So the family took an air ambulance flight from their home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore. It was here, in the pediatric intensive care unit, that they came to understand that Matthew had Rasmussen’s encephalitis, a rare, chronic inflammatory disease. The problem with the disease is that it affects not just a small bit of the brain but an entire half. Valerie and Jim explored their options and were alarmed to learn there was only one known treatment for Matthew’s condition: a hemispherectomy, or the surgical removal of an entire half of the brain. “I can’t tell you anything the doctors said after that,” Valerie told me. “One just shuts down, like everyone’s talking a foreign language.”

Valerie and Jim tried other approaches, but they proved fruitless. When Valerie called Johns Hopkins hospital to schedule the hemispherectomy some months later, the doctor asked her, “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Can you look in the mirror every day and know you’ve chosen what you’ve needed to do?”

Valerie and Jim couldn’t sleep beneath the crushing anxiety. Could Matthew survive the surgery? Was it even possible to live with half of the brain missing? And even if so, would the removal of one hemisphere be so debilitating as to offer Matthew a life on terms not worth taking?

But there were no more options. A normal life couldn’t be lived in the shadow of multiple seizures each day. They found themselves weighing Matthew’s assured disadvantages against an uncertain surgical outcome.

Matthew’s parents flew him to the hospital in Baltimore. Under a small child-sized mask, Matthew drifted away into the anesthesia. A blade carefully opened a slit in his shaved scalp. A bone drill cut a circular burr hole in his skull.

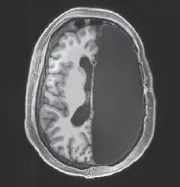

Working patiently over the course of several hours, the surgeon removed half of the delicate pink material that underpinned Matthew’s intellect, emotion, language, sense of humor, fears, and loves. The extracted brain tissue, useless outside its biological milieu, was banked in small containers. The empty half of Matthew’s skull slowly filled up with cerebrospinal fluid, appearing in neuroimaging as a black void.2

Half of Matthew’s brain was surgically removed.

In the recovery room, his parents drank hospital coffee and waited for Matthew to open his eyes. What would their son be like now? Who would he be with only half a brain?

Of all the objects our species has discovered on the planet, nothing rivals the complexity of our own brains. The human brain consists of eighty-six billion cells called neurons: cells that shuttle information rapidly in the form of traveling voltage spikes.3 Neurons are densely connected to one another in intricate, forest-like networks, and the total number of connections between the neurons in your head is in the hundreds of trillions (around 0.2 quadrillion). To calibrate yourself, think of it this way: there are twenty times more connections in a cubic millimeter of cortical tissue than there are human beings on the entire planet.

But it’s not the number of parts that make a brain interesting; it’s the way those parts interact.

In textbooks, media advertisements, and popular culture, the brain is typically portrayed as an organ with different regions dedicated to specific tasks. This area here exists for vision, that swath there is necessary for knowing how to use tools, this region becomes active when resisting candy, and that spot lights up when mulling over a moral conundrum. All the areas can be neatly labeled and categorized.

But that textbook model is inadequate, and it misses the most interesting part of the story. The brain is a dynamic system, constantly altering its own circuitry to match the demands of the environment and the capabilities of the body. If you had a magical video camera with which to zoom in to the living, microscopic cosmos inside the skull, you would witness the neurons’ tentacle-like extensions grasping around, feeling, bumping against one another, searching for the right connections to form or forgo, like citizens of a country establishing friendships, marriages, neighborhoods, political parties, vendettas, and social networks. Think of the brain as a living community of trillions of intertwining organisms. Much stranger than the textbook picture, the brain is a cryptic kind of computational material, a living three-dimensional textile that shifts, reacts, and adjusts itself to maximize its efficiency. The elaborate pattern of connections in the brain—the circuitry—is full of life: connections between neurons ceaselessly blossom, die, and reconfigure. You are a different person than you were at this time last year, because the gargantuan tapestry of your brain has woven itself into something new.

When you learn something—the location of a restaurant you like, a piece of gossip about your boss, that addictive new song on the radio—your brain physically changes. The same thing happens when you experience a financial success, a social fiasco, or an emotional awakening. When you shoot a basketball, disagree with a colleague, fly into a new city, gaze at a nostalgic photo, or hear the mellifluous tones of a beloved voice, the immense, intertwining jungles of your brain work themselves into something slightly different from what they were a moment before. These changes sum up to our memories: the outcome of our living and loving. Accumulating over minutes and months and decades, the innumerable brain changes tally up to what we call you.

Or at least the you right now. Yesterday you were marginally different. And tomorrow you’ll be someone else again.

LIFE’S OTHER SECRET

In 1953, Francis Crick burst into the Eagle and Child pub. He announced to the startled swillers that he and James Watson had just discovered the secret of life: they had deciphered the double-helical structure of DNA. It was one of the great pub-crashing moments of science.

But it turns out that Crick and Watson had discovered only half the secret. The other half you won’t find written in a sequence of DNA base pairs, and you won’t find it written in a textbook. Not now, not ever.

Because the other half is all around you. It is every bit of experience you have with the world: the textures and tastes, the caresses and car accidents, the languages and love stories.4

To appreciate this, imagine you were born thirty thousand years ago. You have exactly your same DNA, but you slide out of the womb and open your eyes onto a different time period. What would you be like? Would you relish dancing in pelts around the fire while marveling at stars? Would you bellow from a treetop to warn of approaching saber-toothed tigers? Would you be anxious about sleeping outdoors when rain clouds bloomed overhead?

Whatever you think you’d be like, you’re wrong. It’s a trick question.

Because you wouldn’t be you. Not even vaguely. This caveman with identical DNA might look a bit like you, as a result of having the same genomic recipe book. But the caveman wouldn’t think like you. Nor would the caveman strategize, imagine, love, or simulate the past and future quite as you do.

Why? Because the caveman’s experiences are different from yours. Although DNA is a part of the story of your life, it is only a small part. The rest of the story involves the rich details of your experiences and your environment, all of which sculpt the vast, microscopic tapestry of your brain cells and their connections. What we think of as you is a vessel of experience into which is poured a small sample of space and time. You imbibe your local culture and technology through your senses. Who you are owes as much to your surroundings as it does to the DNA inside you.

Contrast this story with a Komodo dragon born today and a Komodo dragon born thirty thousand years ago. Presumably it would be more difficult to tell them apart by any measure of their behavior.

What’s the difference?

Komodo dragons come to the table with a brain that unpacks to approximately the same outcome each time. The skills on their résumé are mostly hardwired (eat! mate! swim!), and these allow them to fill a stable niche in the ecosystem. But they’re inflexible workers. If they were airlifted from their home in southeastern Indonesia and relocated to snowy Canada, there would soon be no more Komodo dragons.

In contrast, humans thrive in ecologies around the globe, and soon enough we’ll be off the globe. What’s the trick? It’s not that we’re tougher, more robust, or more rugged than other creatures: along any of these measures, we lose to almost every other animal. Instead, it’s that we drop into the world with a brain that’s largely incomplete. As a result, we have a uniquely long period of helplessness in our infancy. But that cost pays off, because our brains invite the world to shape them—and this is how we thirstily absorb our local languages, cultures, fashions, politics, religions, and moralities.

Dropping into the world with a half-baked brain has proven a winning str...

Table of contents

- 1.The Electric Living Fabric

- 2. Just Add World

- 3. The Inside Mirrors the Outside

- 4. Wrapping Around the Inputs

- 5. How to Get a Better Body

- 6. Why Mattering Matters

- 7. Why Love Knows Not Its Own Depth Until the Hour of Separation

- 8. Balancing on the Edge of Change

- 9. Why Is It Harder to Teach Old Dogs New Tricks?

- 10. Remember When

- 11. The Wolf and the Mars Rover

- 12. Finding Ötzi’s Long-Lost Love

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Index

- Illustration Credits