- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

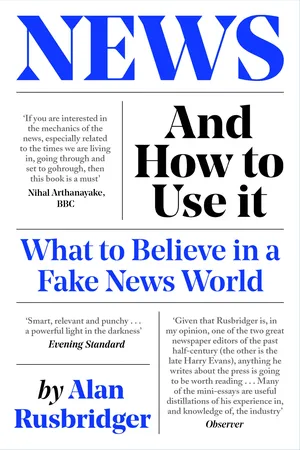

About this book

A society that isn't sure what's true can't function, but increasingly we no longer seem to know who or what to believe. We're barraged by a torrent of lies, half-truths and propaganda: how do we even identify good journalism any more?

At a moment of existential crisis for the news industry, in our age of information chaos, News and How to Use It shows us how. From Bias to Snopes, from Clickbait to TL;DR, and from Fact-Checkers to the Lamestream Media, here is a definitive user's guide for how to stay informed, tell truth from fiction and hold those in power accountable in the modern age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access News and How to Use It by Alan Rusbridger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Media & Communications Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A

ACCURACY

There is the technically correct attitude towards accuracy, and then there is the sometimes messy reality. The following is roughly what you will be taught in journalism school:

‘Accuracy is the essence of journalism. Anyone can – and will – make mistakes but getting basic and easily checkable information wrong is hard to forgive. Names. Numbers. Addresses. These cannot be fudged if they are wrong: they are either correct or incorrect. If a news organisation has to make a correction, the whole piece feels tainted. If there is a mistake in the basics, how can a reporter be relied upon to get right complex and contentious issues addressed elsewhere in a piece?’

The advice will continue in this vein:

‘Once a story is finished, re-read it to catch typos or other mistakes, and there invariably will be some. Some reporters will press send in expectation that a news editor, sub-editor or copy editor will pick up errors. Unfair. News editors, sub-editors and copy editors regularly pick up mistakes but the accuracy of a piece remains 100 per cent the responsibility of the writer. A mistake made while writing to a tight deadline is understandable but it is no defence. When there is no pressing deadline, the best journalists read and re-read a piece as much as they can, maybe even leaving it overnight to look at it again fresh in the morning. And then check again. And again.’

All good advice, and yet it feels like only the beginning. Note the 1947 Hutchins Commission into journalism in the US and its warnings about publishing accounts that are ‘factually correct but substantially untrue’. Or read the German-American political theorist Hannah Arendt in 1961 asking the question: ‘Do facts, independent of opinion and interpretation, exist at all? Have not generations of historians and philosophers of history demonstrated the impossibility of ascertaining facts without interpretation, since they must first be picked out of a chaos of sheer happenings (and the principles of choice are surely not factual data) and then be fitted into a story that can be told only in certain perspective, which has nothing to do with the original occurrence?’

Or note the carefully qualified BBC Academy definition of accuracy – or, as the corporation prefers to term it, ‘due accuracy’.

What is ‘due’? ‘The term “due” means there is no absolute test of accuracy; it can mean different things depending on the subject and nature of the output, and the expectations and understanding of the audience.’ The Academy then echoes the Hutchins Commission: ‘Accuracy isn’t the same as truth – it’s possible to give an entirely accurate account of an untruth.’

Accuracy is, you might say, a destination: the journey is what defines journalism. If those who wish to practise journalism aren’t striving for accuracy, it isn’t journalism. But can even the journalists always – or even mostly – achieve it?

Take something apparently simple, such as the height of Mount Everest. It is a huge lump of rock, not the shifting sands of opinion . . . Isn’t it? Actually, it is much more complicated than that and turns on – among other things – who did the measuring, when and how, and the nature of geology. Here is the online Encyclopaedia Britannica: ‘Controversy over the exact elevation of the summit developed because of variations in snow level, gravity deviation, and light refraction. The figure 29,028 feet (8,848 metres), plus or minus a fraction, was established by the Survey of India between 1952 and 1954 and became widely accepted. This value was used by most researchers, mapping agencies, and publishers until 1999 . . . [In that year there was] an American survey, sponsored by the (U.S.) National Geographic Society and others, [which] took precise measurements using GPS equipment. Their finding of 29,035 feet (8,850 metres), plus or minus 6.5 feet (2 metres), was accepted by the society and by various specialists in the fields.’ The Chinese and the Italians disagree and have their own figures. So a journalist in a hurry (i.e. most journalists, most of the time) could easily stub their toe even on a relatively innocent-sounding issue such as the height of a mountain.

Now imagine the intricacies of reporting on climate change (SEE: CLIMATE CHANGE) – at any point in the chain from publication to subsequent arbitration or regulation – and having to exercise judgement over such bitterly contested territory.

The British press regulator, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso), regularly finds itself struggling to decide how to reach a view on the accuracy of competing claims about global warming. Typically, one or more distinguished scientists will complain about an article – often a comment piece – and point out what they claim to be significant inaccuracies. The publisher usually responds by arguing that this is merely a disagreement between people with strong views and that, anyway, comment should be free. Accuracy, in other words, is a matter of interpretation.

Ipso, in common with nearly every editor having to evaluate stories about climate change, simply does not have the in-house expertise to make judgements about the science. It therefore tends to consider the processes of checking or verification that were undertaken in advance of publication, as well as the steps to clarify or correct after the event. But on the issue of accuracy itself it is, more often than not, silent.

Transgender issues are another minefield in which Ipso’s view of accuracy may turn on disputed use of terminology in an increasingly polarised debate in which different participants insist on ‘their’ truth.

Then there are foreign policy issues such as Israel–Palestine, in which the two sides can barely agree on anything to do with language, geography, history, religion or ethnicity, and where well-resourced special-interest groups monitor and stand ready to contest every mainstream article or broadcast.

When do you use the word ‘assassination’ (rather than ‘killing’)? Is it a wall, or a barrier, or a fence, or a separation barrier? Is it a border, or a boundary, or a green line, or the 1949 Armistice Line? Is there such a thing as a ‘cycle of violence’? If so, who started it – or is better not to go there?

Is an outpost the same as a settlement? Are all settlements illegal? If the Israelis dispute that, should you always say so? Do the Occupied Territories refer to Palestinian land or territories? What is ‘Palestine’? Is there such a thing as a ‘right’ of return, and does it apply equally to Jews and Palestinians? When, if ever, do you use the word ‘terrorist’?

All these conundrums are outlined by the BBC editorial guidelines and taught by the BBC Academy. Anyone who has ever had any involvement with reporting on the Middle East (or transgender issues, or climate change) will quickly discover that the term ‘accuracy’ – apparently so clear-cut and simple when taught in J-school – can, in fact, be a quagmire.

ACTIVE READER

A viewer slouched in front of their TV is the classic passive audience for news. A newspaper reader may make some more positive choices about what to read, and what to ignore, but is essentially in the same role of passively consuming the news.

But what happens when four billion people on the planet become connected and have the ability to respond, react, challenge, contribute? Will more of them become ‘active readers’?

Active reading can, in academic terms, simply refer to the art of reading for comprehension – underlining, highlighting, annotating, questioning and so on. But, as social media took root, a few news organisations tested how willing their readers were to become involved in the process of news-gathering and editing. At the heart of this was the early digital age (1999) dictum of Dan Gillmor, then on the San Jose Mercury News: ‘My readers know more than I do.’ Not always true, but true enough to make the active reader an interesting concept.

The Dutch news site De Correspondent was born with the idea of incorporating active readers from the start. Jay Rosen, the NYU professor who became an adviser to the organisation, explained how the journalists were expected to have a radically different relationship with the reader than in traditional media. ‘Expectations are that writers will continuously share what they are working on with the people who follow them and read their stuff. They will pose questions and post call-outs as they launch new projects: what they want to find out, the expertise they are going to need to do this right, any sort of help they want from readers. Sometimes readers are the project. Writers also manage the discussion threads – which are not called comments but contributions – in order to highlight the best additions and pull useful material into the next iteration of an ongoing story.’ Some of these crowdsourcing techniques have been used by journalists on more mainstream papers, notably David Fahrenthold of the Washington Post.

The Drum profiled how De Correspondent works, using health as an example of how the reader can move from passive to active: ‘De Correspondent’s philosophy is that 100 physician readers know more than one healthcare reporter. So when that healthcare reporter is prepping a story, they announce to readers what they’re planning to write and ask those with first-hand knowledge of the issues – from doctors to patients – to volunteer their experiences.’ The site’s co-founder Ernst-Jan Pfauth is quoted saying: ‘By doing this we get better-informed stories because we have more sources from a wider range of people . . . It’s not just opinion-makers or spokespersons, we get people from the floor. And, of course, there are business advantages because we turn those readers into more loyal readers. When they participate that leads to a stronger bond between the journalist and the reader.’

The British news website Tortoise, a ‘slow news’ outlet launched in 2019, adopted a similar principle: ‘We want ours to be a newsroom that gives everyone a seat at the table,’ wrote the editor James Harding (a former editor of the Times and director of BBC News), ‘one that has the potential to be smarter than any other newsroom, because it harnesses the vast intelligence network that sits outside it; one that doesn’t just add to the cacophony of opinions but prioritises and distils information into a clear point of view.’

With that aim they opened up their editorial conferences for readers to contribute. It was a bold and imaginative idea. Time will tell whether the tortoise eventually wins.

AGGREGATORS

One of the great dilemmas facing publishers since the birth of social media has been whether they should sit back and expect readers to come to their own platforms, or go to where the audiences actually were. The big tech companies smelled this weakness and created news aggregators. Join them, or dare ignore them?

Facebook, a huge driver of traffic to news sites, decided it was better to keep readers within its own proprietary ecosystem. Apple News was launched in 2015 and by 2019 had ‘roughly 90 million’ regular users. That’s a big number – but publishers were unimpressed by the revenues they received from advertising, even if some of them liked the exposure and the ability to drive subscriptions.

Apple News followed in the footsteps of Google News (2002), available in thirty-five languages and said to be scraping more than 50,000 news sources across the world. Again, publishers could not decide if it was, on balance, a good thing (traffic, marketing, visibility) or bad (‘theft’, ‘monetising our intellectual property’). Assorted publishers – even entire countries – resorted to legal action. Google sometimes responded by fighting the claims or sometimes by simply dropping content.

It soon became a crowded field. Feedly offered a personalised experience. AllTop even aggregated other aggregators (such as Reddit). Flipboard tried to win by feeding everything into a magazine-style layout. TweetDeck enables readers to break down their Twitter feeds by writer, issue or location. And so on.

The best aggregators are so expert at content distribution that it appears to make sense for some publishers to regard them as the main, or only, platform of distribution. But – apart from the commercial downsides (cannibalisation, lack of transparency and data, loss of a direct relationship with the reader) – there is also the problem that some readers stop even noticing which news organisation has created the original article: ‘I read it on Facebook.’ If you’re trying to build a news organisation based on trust, but the readers can no longer easily distinguish your brand from any other, then you have a problem.

ATOMISATION

A printed newspaper was an amalgamation of a hundred or more issues, sections or passions. News, foreign news, football, weather, golf, fashion, crime, politics, crosswords, recipes, finance, relationships, human rights, education, sex advice, editorials . . . and much, much more. It was not long into the digital age before the penny dropped that almost every one of those segments or niches could be done better and in more depth on its own. The crossword no longer needed to be bundled up with news from Iraq or the share prices. The football didn’t belong with the book reviews or the parliamentary reports. Welcome to the world of atomisation.

Everything has been atomised. Long stories are fragmented into simpler formats and chunks – a shareable tweet, an Instastory. The once-homogenised audience becomes a million individuals, each with their own personal obsessions and interests. Some want to delve, others to snack. Different subjects are targeted at various platforms. We are in an era of infinite choice. One-size-fits-all will, of course, live on so long as newspapers are printed and news bulletins broadcast. But the atomisation of everything else is here to stay.

ATTRIBUTION

Easy citation might be the humble hyperlink’s greatest contribution to media.

In 2010, a New York Times Magazine article came under fire for heavy overlap with another author’s work. In an op-ed, the NYT’s public editor (an independent editor tasked with overseeing journalistic integrity – a position the paper eliminated in 2017) responded by declaring that the issue went deeper than intellectual theft: it was a problem with journalism itself. ‘Murky’ rules for attribution make reporting much less transparent than academic scholarship, which has a strict set of rules (SEE: FOOTNOTES).

So, the public editor prescribed links. A few hyperlinks to the articles of the accusing author, he suggested, could have given due credit, boosted her reputation, and put to good use the ‘digital medium’s distinct properties’. A win-win-win.

B

BIAS

The US and UK are mirror images of each other. In the UK most broadcasting is pretty strictly regulated, with an expectation that it strives to be impartial (SEE: IMPARTIALITY). The national printed press, by contrast, springs from different roots: a two- or three-hundred-year tradition of political attachment.

In the US the positions are reversed. There, most newspapers attempt to be as balanced as they can, in their reporting at least, and it is the broadcasters – think Fox News and much of ta...

Table of contents

- Preface

- A–Z

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements