- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

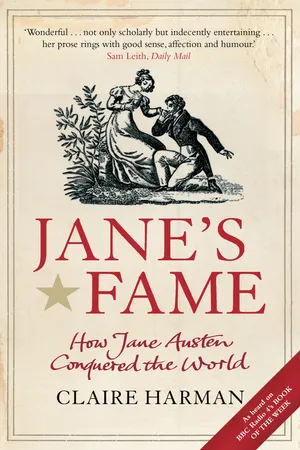

Part biography and part cultural history, this splendid book not only tells the captivating story of Jane Austen's life, but also her literary legacy. The slow growth of Austen's fame, the changing status of her work, and what it has stood for in English culture is a story of personal struggle and family dynamics as well as a history of critical practices and changing public tastes.

Jane's Fame is essential reading for anyone interested in Austen's life, works and unshakable appeal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jane's Fame by Claire Harman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

‘Authors too ourselves’

In 1869, Jane Austen’s first biographer, James Edward Austen-Leigh, expressed surprise at how his aunt had managed to write so much in the last five years of her life, living in the close quarters of Chawton Cottage with her mother, sister, friend Martha Lloyd and a couple of servants. ‘She had no separate study to retire to,’ said James Edward, with evident pity, ‘and most of the work must have been done in the general sitting-room, subject to all sorts of casual interruptions.’ Careful to conceal her occupation from ‘servants, or visitors, or any persons beyond her own family party’,1 he described how she wrote ‘upon small sheets of paper which could easily be put away, or covered with a piece of blotting paper’. A squeaking swing door elsewhere in the cottage gave her warning whenever someone was approaching, and time to hide the latest sheet of ‘Mansfield Park’, ‘Emma’, ‘Persuasion’ or ‘Sanditon’.

Quite where this famous story originated is a puzzle, as James Edward goes on to say that neither he nor his sisters (the main sources of all anecdotage about Austen) were ever aware of disturbing their aunt at her writing, and he makes it clear that there was no attempt at concealment ‘within her own family party’. But secrecy about her work became a cornerstone of the Austen myth; the image conjured up was of the endlessly patient genius putting the demands of family life, however petty, before her work, writing, when she could, in guarded but modest isolation in a corner of a shared sitting-room.

The truth is that Jane Austen never exhibited self-consciousness or shame about her writing, and never needed to. Unlike many women writers of her generation – or stories about them – she had no struggle for permission to write, no lack of access to books, paper and ink, no frowning paterfamilias to face down or from whom to conceal her scribbling. Her ease and pleasure in writing as an occupation are evident from the very beginning, as is the full encouragement of her family, and if there was little space in her various homes, that was more a simple fact of life and square-footage in relatively cramped households than a metaphor for creative limitations.

What James Edward Austen-Leigh’s testimony really reveals is not the author’s lack of vanity but how much her writing was accepted, and even overlooked, within her family. Austen is now such a towering figure in literature and myth that it is hard to reinsert her in her home environment and not still see a genius: even James Edward was blinded by the awe-factor by the time he came to write her biography, fifty years after his aunt’s death. A generation younger than her, he was one of the last to find out that Aunt Jane was the anonymous ‘Author of “Sense & Sensibility”, “Pride & Prejudice” etc.’ His surprise at this news, and his subsequent interest in his aunt, mark him out as not of the inner circle. They were not so susceptible to awe.

This is not to say that Austen’s closest family were indifferent to her ambitions and achievements as a writer, or callously withholding of praise, but that the home context of genius is by definition utterly unlike any other. According to the theorist Leo Braudy, fame can be thought of as having four elements: a person, an accomplishment, their immediate publicity and what posterity makes of them.2 The ‘immediate publicity’ of Jane Austen’s fame is interesting not so much in how and where her books were reviewed or what her contemporaries thought of them, but in how she was treated in her own circle, and what sort of climate that provided. And the reason why Jane Austen did not require, or receive, any special treatment within her family was that she was by no means the only writer among them.

Jane was the second youngest of the Austen children, ten years younger than her eldest brother, James, and two years younger than her only sister, Cassandra. She was born and lived the first twenty-six years of her life at Steventon, on the north-easterly edges of Hampshire; her father, the Reverend George Austen, was a clever, gentle man, her mother, Cassandra Leigh, a highly articulate woman with aristocratic ancestors, niece of a famous Oxford scholar and wit. The family was only modestly well-off, and Jane’s lively, good-looking and accomplished brothers had to make their own ways in the world; James and Henry, both Oxford graduates, joined the Church and the Army, Francis and Charles joined the Navy, and lucky Edward was adopted by childless relatives, Mr and Mrs Thomas Knight of Godmersham, sent on the Grand Tour and made heir to their estates in Kent and Hampshire. Only George, the second son, did not share the family’s health and success; disabled in some way, he spent his life being cared for elsewhere and hardly appears in the family records at all.

Jane and her beloved elder sister Cassandra grew up surrounded by boys, for the Reverend Austen supplemented his clerical income by taking in pupils, running in effect a small school for the sons of the local gentry. Though the girls were later sent away to school briefly in Oxford, Reading and Southampton, they spent most of their childhood in the more challenging intellectual atmosphere of their own home. At the Rectory, there was a well-stocked library that included works of history, poetry, topography, the great essayists of the century, and plenty of fiction, for the Austens were ‘great Novel-readers & not ashamed of being so’3 and subscribed to the local circulating library, which held copies of all the recent bestsellers. Jane was a fan of Fanny Burney and Maria Edgeworth, Charlotte Smith, Mrs Radcliffe, Mrs Inchbald and a host of less memorable eighteenth-century romancers, lapping up their stories and lampooning their more absurd conventions with equal glee. ‘From an early age,’ the critic Isobel Grundy has noted, ‘she read like a potential author. She looked for what she could use – not by quietly absorbing and reflecting it, but by actively engaging, rewriting, often mocking it.’4

Like the eponymous heroine of her early story, ‘Catharine, or the Bower’, the teenaged Jane was ‘well-read in Modern History’ and left more than a hundred marginal notes in a schoolroom copy of Oliver Goldsmith’s 1771 History of England, still in the possession of the Austen family. Her cheeky ripostes, mostly in defence of her favourites, the Stuarts, give a strong impression of her intellectual confidence, as well as of her pleasure in acting as the classroom wit. In the same irreverent spirit, Austen wrote her own pro-Stuart ‘History of England’ in 1791, for recital and circulation among the family. Her section on Henry VIII begins like this:

It would be an affront to my Readers were I to suppose that they were not as well acquainted with the particulars of this King’s reign as I am myself. It will therefore be saving them the task of reading again what they have read before, and myself the trouble of writing what I do not perfectly recollect, by giving only a slight sketch of the principal Events which marked his reign.5

When ‘The History of England’ was eventually published, in 1922, Virginia Woolf characterised the girlish author as ‘laughing, in her corner, at the world’, but the writer of such a brilliant comic party-piece was hardly the shrinking (or smirking) violet Woolf imagines, but a quick-witted, praise-hungry teenager, competing for attention in a close, loving, intellectually competitive household. With people outside her immediate circle, whose approval she didn’t seek or value, Austen was likely to fall silent; hence her cousin Philadelphia’s description of Jane in 1788 as ‘whimsical & affected … not at all pretty & very prim, unlike a girl of twelve’.6 The family, especially those she was closest to, Cassandra, Henry, Frank, Charles and her father, would have known very well how ‘unlike a girl of twelve’ Jane was, how fanciful and how funny. But she didn’t always choose to perform.

In the years between 1788 and 1792, that is, between the ages of twelve and sixteen, Jane copied up her skits, plays and stories into three notebooks titled humorously ‘Volume the First’, ‘Volume the Second’ and ‘Volume the Third’, named as if they were instalments of a conventional three-part novel. There was a habit among the Austens of using high-quality quarto notebooks (and one’s best handwriting) to make, in effect, manuscript books to be passed round and enjoyed in the family; editions of one, but still editions. Much later, in 1812, Jane made a reference in a letter to a comic quatrain she had written, and sent to her brother James for his comments, being added to ‘the Steventon Edition’.7 As with so many of Austen’s familiar references, it’s not clear exactly what she meant by this, but the phrase and its context suggest an album in which the family verses were collected. James Austen’s own poems and verse prologues have survived largely because his three children made copies of them in similar quarto volumes.8

Almost every item in Jane Austen’s juvenilia has an elaborate, mock-serious dedication to one or other member of the family circle; her brothers, both parents, her cousins Eliza de Feuillide and Jane Cooper, and friends Martha and Mary Lloyd. Cassandra, who had provided Jane with thirteen charming watercolour vignettes as illustrations to ‘The History of England’, received this dedication to ‘Catharine, or the Bower’, Jane’s unfinished but ambitious early novel:

Madam

Encouraged by your warm patronage of The beautiful Cassandra, and The History of England, which through your generous support, have obtained a place in every library in the Kingdom, and run through threescore Editions, I take the liberty of begging the same Exertions in favour of the following Novel, which I humbly flatter myself, possesses Merit beyond any already published, or any that will ever in future appear, except as may proceed from the pen of Your Most Grateful Humble Servt. The Author9

Behind the humour is a familiarity with book production and distribution as well as patronage, and a tacit acknowledgment of her own ambitions, which ‘Catharine, or the Bower’ (the only substantial non-burlesque story by Jane to have survived from these early years) was clearly meant to advance.

Jane’s writing was encouraged in particular by her father, with whom she was something of a favourite (Mrs Austen favoured her first-born, James). The portable writing-desk which Jane bequeathed to her niece Caroline, and which is now on display in the British Library, is thought to have been a gift from him.10 He certainly gave her the white vellum notebook which became ‘Volume the Second’ (she has inscribed it ‘Ex Dono Mei Patris’), and probably also provided Volume the Third, as he wrote a mock-commendation inside the front cover: ‘Effusions of Fancy/by a very Young Lady/Consisting of Tales/in a Style entirely new’, sportingly joining in the spirit of her enterprise. In Austen’s surviving letters, the earliest of which dates from 1796, it is her father who is depicted as most close to her own interest in books, literary periodicals and the circulat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Daniel H. Pink

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Chapter 1 ‘Authors too ourselves’

- Chapter 2 Praise and Pewter

- Chapter 3 Mouldering in the Grave

- Chapter 4 A Vexed Question

- Chapter 5 Divine Jane

- Chapter 6 Canon and Canonisation

- Chapter 7 Jane Austen™

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Manuscript Sources

- Select Bibliography

- Notes

- Index