- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

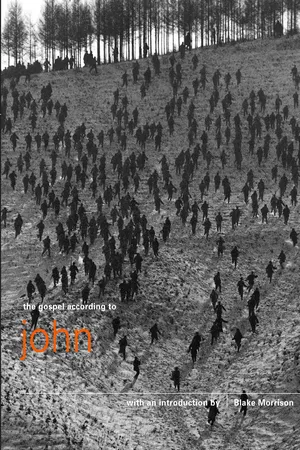

The Gospel According to John

About this book

In both the literary sense and content, this gospel differs dramatically from the others in that it expresses the movement towards agnosticism and is more concerned with explaining high concepts like truth, light, life and spirit than recounting historical fact. With an introduction by Blake Morrison.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Gospel According to John by Blake Morrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Bibles. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

introduction by blake morrison

From the age of eight to fifteen, I spent every Sunday morning in the choirstalls of an English village church. To be in the choir didn’t require singing talent. You just turned up each week and stood there, like something out of Thomas Hardy, raising a song in praise of God, to the accompaniment of a wheezing organ. Our predecessors in the graveyard had done the same. The dusty black cassocks and white surplices waiting for us on pegs in the vestry – they had worn them, too. The choir was small, just six or eight, all children, most of them present under parental duress. With me, it was different: my father was an atheist, my mother an Irish Catholic, and I’d had to fight to join up. It was not that I had a sense of calling. It was simply a way of getting to see my friends on Sunday. We weren’t always well-behaved. Gum was surreptitiously chewed during prayers, then deposited in sticky balls and left to harden. Cruel names were invented for those in the paltry congregation. Whispering and giggling were routine. Still, until confirmation (which for me confirmed doubts, not faith) we kept coming. And though I’m no church-goer now, those Sundays will always be part of me. The touch of cold stone flags on a bended knee; the lovely sound of ‘daily bread’ and ‘trespasses’; the melting nothingness (neither flesh nor manna) of a communion wafer; the head-swoon from a sip of wine; the rotting-body smell from water that stood too long in flower-vases; the whitewash walls, the spread-winged golden-eagle lectern stand, the pale-lemon morning light, the wood of the nave so dark it might have been burned – the hours of boredom have long faded, but the sensuousness has stayed.

The Gospels have stayed, too, the miracles and sayings and Passion. To begin with, I preferred the Old Testament, which read like a boy’s adventure story spanning several generations: Noah’s flood, David’s slingstone, Daniel in the lion’s den, Moses in his basket, the parting of the Red Sea. Jesus had adventures, too, but you’d not have known it from the face in the stained-glass windows. He looked wan, frozen and passive, too pious for his own good – someone who’d change wine to water, not the other way about. The only impressive thing about him was that it had taken four men to tell his tale. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John: the names sounded familiar, reassuring, trustworthy, and it didn’t seem surprising that their stories should vary – when my friends and I related the same events, didn’t our versions vary, too? As years passed in the choir-stalls, I became more interested in the Apostles, and tried to put faces to their names. John was the hardest to visualise. He was said to be the son of Zebedee, ‘the beloved disciple’, but this didn’t help much. All I did dimly perceive was that he was the odd one out.

At fifteen, I swapped the Apostles for another Fab Four, the Beatles, whose John was likewise the outsider. Soon enough, the phrase ‘gospel truth’ had a hollow ring for me – I was discovering stranger, more various truths through drink, drugs, girls, music, the mystic east. The only lingering affection I felt for the c of e came from thinking of Jesus’s story as myth or legend – literary fiction, not monotheistic truth. The idea that the Apostles were contemporaries of Christ, writing factual first-hand reports, seemed ridiculous. But once I thought of them as storytellers, drawing on oral tradition, their gospels became more interesting. They were pedagogues, trying to convince others to follow their faith. But they were also, at least in the Authorised Version, hauntingly imaginative writers, John above all.

The literary status of the gospels, the identity of their authors, the degree of historical truth they impart – these are matters scholars debate to this day. Agreement is rare, but one can glimpse a consensus of sorts on several points.

— A man called Jesus did live and preach in Palestine shortly after the time of King Herod’s death; a radical thinker and militant leader, he ran into trouble with the authorities and was put to death.

— Matthew, Mark, Luke and John wrote their gospels late in the first century, perhaps drawing on eye-witness accounts that had been passed down: their names were assigned to the Gospels only around 180 ad, and they probably worked closely with other Christian opinion-formers, in effect as editorial teams.

— Each gospel went through several versions, perhaps as many as five, building up from sayings and sermons through ‘peri-copes’ (teaching or episodic units) to full-blown narratives.

— Their purpose was to proclaim the ‘good news’ of Jesus’s life, through accounts of his story and teachings: ‘these are written, that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing ye might have life through his name’ (John 20:31).

— Mark was the first gospel to be composed and John is probably the last.

The apparently late composition of John’s gospel is one of several reasons why it’s often treated as marginal and inferior. Its resemblance to Mark (and Luke) suggests that, if not directly dependent on them, it drew on the same sources for episodes such as the walk on the lake, the feeding of the 5,000 and the miraculous draught of fishes. The chronology of the first three (‘synoptic’) gospels coincides to a very large degree, whereas John (’the fourth gospel’) differs in suggesting that Jesus’s ministry lasted over three Passovers, not one, and in putting the scourging of the Temple episode early on. The synoptic gospels are also fairly consistent about the teachings of Jesus, whereas what he preaches in John shows the influence of later schools of thought, including the Hellenistic and the Hermetic. Many commentators find the structure of John dislocated and suggest an alternative arrangement of the chapters. All in all, as E P Sanders puts it in his study The Historical Figure of Jesus, ‘The synoptic gospels are to be preferred as our basic source of information about Jesus.’

What claims can be made for John, then? First, it is the most poetic of the gospels. Compare the various openings. Matthew begins with a dull, Old Testament-like genealogical table: ‘Abraham begat Isaac; and Isaac begat Jacob; and Jacob begat Judas’, etc. Mark goes in for skittish anecdotes and dress-notes about John the Baptist: ‘John was clothed with camel’s hair, and with a girdle of skin’. Luke writes in drab bureaucratese to Theophilus, the recipient of his missive: ‘Forasmuch as many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us …’ By contrast, John opens with one of the greatest passages of poetic prose in the language, philosophically dense, metaphorically rich and rhythmically lucid at the same time:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not … And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father), full of grace and truth. (1:1–5, 14)

John is thick with symbols and incantations: light, darkness, bread, water, flesh, word. It’s also full of lines that have gone into the language: ‘God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son …’; ‘Rise, take up thy bed, and walk’; ‘He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her’; ‘I am the good shepherd’; ‘I am the resurrection, and the life’; ‘The poor always ye have with you’; ‘In my father’s house are many mansions’; ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’; ‘Put up thy sword into thy sheath’; ‘What I have written I have written’. Part of what makes John special is that it uses metaphors where the other Gospels use similes. ‘Destroy this temple,’ Jesus tells the Jews, speaking not of their temple but his body, ‘and I will raise it up’ (2:19). ‘Whosoever drinketh of this water shalt thirst again,’ he tells the woman of Samaria by her well, ‘but whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst’ (3:13–14). ‘I have meat to eat that ye know not of,’ he tells his disciples, ‘… my meat is to do the will of him that sent me’ (4:32–4). Or again to his disciples: ‘I am the bread of life: he that cometh to me shall never hunger …’ (6:35). Or again: ‘I am the light of the world’ (8:12). Or: ‘I am the true vine, and my Father is the husbandman’ (15:1).

Metaphors aren’t always easy to understand. They trouble the literal-minded. Jesus causes this trouble. One of the themes of John’s gospel is the difficulty people have in communicating with one another. Jesus’s protracted metaphor about entering into a sheepfold leaves his listeners baffled: ‘they understood not what things they were which he spake unto them’ (10:6). Talk of the impossibility of their following him also causes confusion: ‘Then said the Jews, “Will he kill himself?” Because he saith, “Whither I go, ye cannot come.”’ Nicodemus is perplexed by the promise of rebirth: how can a man be reborn, he asks, stirring Jesus into new poetry: ‘Marvel not that I said unto thee, “Ye must be born again.” The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is everyone that is born of the Spirit.’ John’s Jesus is more seer-like than the Jesus of the other gospels: a prophet, an enigma, a stranger from heaven. He is in touch with truths that defy easy comprehension. But he’s also self-aware enough to realise his listeners sometimes find him hard-going: ‘I have yet many things to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now.’ He doesn’t bear listening to in part because he’s gnomic. Or if not gnomic, Gnostic. He speaks an alien language, the poetry of God.

John’s characterisation of Jesus is another reason why this Gospel stands out. Far from being meek and mild, Jesus here is self-assured, pushy, and somewhat dislikeable. It may not have been the author’s intention, but we see why he caused such anger and resentment, and understand his enemies’ wish to have him dead and out of the way. When he’s not speaking in riddles, he’s argumentative. He hectors. He harangues. He throws out insults and reproaches. He pulls rank, advertising his credentials as Son of God, Son of Man, Messiah, more divine than human, just passing through: ‘Ye are from beneath; I am from above: ye are of this world; I am not of this world (8:23). There is a ferocious existentialist ‘I am’ about him. Desperate to defeat the doubters, he is not averse to using signs to establish his authority (‘Except ye see signs and wonders, ye will not believe’), which the Jesus of Mark’s gospel refuses to do, implying it would be a stunt, a piece of cheap magic (‘Verily I say unto you, there shall no sign be given unto this generation’). One of the greatest commentators on the fourth gospel, Rudolf Bultmann, has said that ‘Jesus as the Revealer of God reveals nothing but that he is the Revealer.’ If this makes him sound like some latter-day cultist, prone to mystification and Me-ism, it should also be said that he’s robust and resourceful, a cartoon character who keeps getting out of impossible scrapes: ‘They took up stones to cast at him: but Jesus hid himself, and went out of the temple, going through the midst of them, and so passed by’ (8:59). ‘They sought again to take him: but he escaped out of their hand, and went away again beyond Jordan …’ (10:39–40). These escapes continue even after the crucifixion, first when Pilate’s soldiers fail to carry out an order to break his legs, then when he disappears from the sepulchre in death as well as life, he constantly outwits his enemies.

The Jesus of John’s Apostle is often described as mystic. But he is worldly as well as otherworldly. When he scourges the temple moneychangers, it’s his physical strength that John emphasises: ‘and when he had made a scourge of small cords, he drove them all out of...

Table of contents

- The Gospel According to John

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- a note about pocket canons

- introduction by blake morrison

- the gospel according to st john

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- About the Author

- Copyright