- 675 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

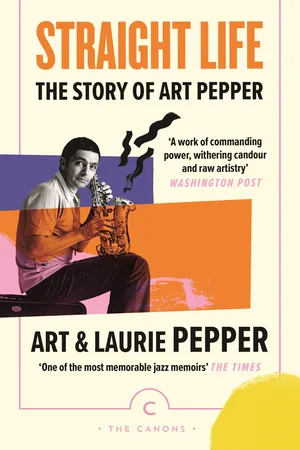

Straight Life: The Story Of Art Pepper

About this book

Art Pepper was described as the greatest alto-saxophonist of the post-Charlie Parker generation. Straight Life, originally narrated on tape to his wife Laurie, is an explosive work chronicling his work amidst a life dealing with alcoholism, heroin addiction, armed robberies and imprisonment.

The result is an autobiography like no other, a masterpiece of the spoken word, shaped into a genuine work of literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Straight Life: The Story Of Art Pepper by Art Pepper,Laurie Pepper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

1925-1954

1 | Childhood 1925–1939 |

MY GRANDMOTHER was a strong person. She was a solid German lady. And she never would intentionally have hurt anyone, but she was cold, very cold and unfeeling. She was married at first to my father’s father and had two sons, and when he died she remarried. And the man that she married liked her son Richard and didn’t like my father whose name was Arthur, the same as mine.

My father’s stepfather beat him and just made life hell for him. Richard was the good guy; he was always the bad guy. When he was about ten years old he couldn’t stand it anymore, so he left home and went down to San Pedro, down to the docks and wandered around until somebody happened to see him and asked him if he would like to go out on a ship as a cabin boy, and so he did. That was how he started.

He went out on oil tankers and freighters doing odd jobs, working in the scullery, cleaning up, running errands. Because he left home, naturally his schooling was stopped, but he always had a strong desire to learn, so he began studying by himself. He was interested in machinery and mathematics. He studied and kept going to sea and eventually, all on his own, he became a machinist on board ship. He went all over the world. He became a heavy drinker, did everything, tried everything. He lived this life until he was twenty-nine years old, never married, and then one day he came into San Pedro on a ship be-longing to the Norton Lilly Line; they’d been out for a long time; he had a lot of money, so he went up to the waterfront to his usual bars. And going into one of them he saw a young girl. She was fifteen years old. Her name was Mildred Bartold.

My mother never knew who her parents were. She remembers an uncle and an aunt who lived in San Gabriel. They were Italian. They seemed to love her but kept sending her away to convents. Finally she couldn’t stand the convents anymore, so she ran away, and she ended up in San Pedro, and she met my father.

She was very pretty at the time with that real Italian beauty, black hair, olive skin. My father had gotten to the point where he was thinking about settling down, getting a job on land, and not going to sea anymore. They met, and he balled her, and he felt this obligation, and I guess he cared for her, too, so he married her.

So here she was. She had finally gotten out into the world and all of a sudden she’s married to a guy that’s been all over, has done all the things she wants to do and is tired of them, and then she finds herself pregnant. She wanted to drink, look pretty, have boyfriends. She was very boisterous, very vociferous. She would get angry and demand things, she wouldn’t change, she wouldn’t bend. Naturally she didn’t want a baby. She did everything she could possibly do to get rid of it, and my father flipped out. That was why he married her. He wanted a child.

She ran into a girl named Betty Ward who was very wild. Betty had two kids, but she was balling everybody and drinking, and she told my mother what to do to get rid of the baby. My mother starved herself and took everything anybody had ever heard of that would make you miscarry, but to no avail. I was born. She lost.

I was born September 1, 1925. I had rickets and jaundice because of the things she’d done. For the first two years of my life the doctors didn’t think I would live but when I reached the age of two, miraculously I got well. I got super healthy.

During this period we lived in Watts, and my father continued going to sea. He hated my mother for what she had tried to do. She was going out with this Betty; I don’t know what they did. They’d drink. I’d be left alone. The only time I was shown any affection was when my mother was just sloppy drunk, and I could smell her breath. She would slobber all over me.

One time when my father had been at sea for quite a while he came home and found the house locked and me sitting on the front porch, freezing cold and hungry. She was out some-where. She didn’t know he was coming. He was drunk. He broke the door down and took me inside and cooked me some food. She finally came home, drunk, and he cussed her out. We went to bed. I had a little crib in the corner, and my dad wanted to get into bed with me. He didn’t want to sleep with her. She kept pulling on him, but he pushed her away and called her names. He started beating her up. He broke her nose. He broke a couple of ribs. Blood poured all over the floor. I remember the next day I was scrubbing up blood, trying to get the blood up for ages.

They’d go to a party and take me and put me in a room where I could hear them. Everybody would be drinking, and it always ended up in a fight. I remember one party we went to. They had put me upstairs to sleep until they were ready to leave. It was cloudy out, and by the time we got there it was night. I looked out the window and became very frightened, and I remember sneaking downstairs because I was afraid to be alone. They were all drinking, and this one guy, Wes—evidently he’d had an argument with his wife. She went into a bathroom that was off the kitchen and she wouldn’t come out; there was a glass door on this bathroom, so he broke it with his fist. He cut his arm, and the thing ended up in a big brawl.

My parents always fought. He broke her nose several times. They realized they couldn’t have me there. My father’s mother was living in Nuevo, near Perris, California, on a little ranch, one of those old farms. They took me out there. I was five. And that was the end of my living with my parents and the beginning of my career with my grandmother. I saw my grandmother, and I saw that there was no warmth, no affection. I was terrified and completely alone. And at that time I realized that no one wanted me. There was no love and I wished I could die.

Nuevo was a country hamlet. Children should enjoy places like that, but I was so preoccupied with the city and with people, with wanting to be loved and trying to find out why other people were loved and I wasn’t, that I couldn’t stand the country because there was nothing to see. I couldn’t find out anything there. Still, to this day, when I’m in the country I feel this loneliness. You come face to face with a reality that’s so terrible. This was a little farm out in the wilderness. There was my grandmother and this old guy, her second husband, I think. I don’t even remember him he was so inconsequential. And there was the wind blowing.

It was a duty for my grandmother. My father told her he would pay her so much for taking care of me; she would never have to worry—he always worked and she knew he would keep his word. I think she was afraid of him, too, for what she had done to him. For what she had allowed to be done to him when he was a child.

My grandmother was a dumpy woman, strong, unintelligent. She knew no answers to any problems I might have or anything to do with academic type things. She was one of those old-stock peasant women. I never saw her in anything but long cotton stockings and long dresses with layers of underclothing. I never saw her any way but totally clothed. When she went to the bathroom she locked the door with a key. Anything having to do with the body, bodily functions, was nasty and dirty and you had to hide away. I don’t know what her feelings were. She never showed them. She had a cat that she gave affection to but none to me. I grew to hate the cat. My grand-mother was—she was just nothing. There was no communication. Whenever I tried to share anything at all with her she would say, “Oh, Junior, don’t be silly!” Or, “Don’t be a baby!” I had a few clothes and a bed, a bed away from her, a bed alone in a room I was scared to death in. I was afraid of the dark.

I was afraid of everything. Clouds scared me: it was as if they were living things that were going to harm me. Lightning and thunder frightened me beyond words. But when it was beautiful and sunny out my feelings were even more horrible because there was nothing in it for me. At least when it was thundering or when there were black clouds I had something I could put my fears and loneliness to and think that I was afraid because of the clouds.

We moved from Nuevo to Los Angeles and then to San Pedro, and during the time of the move to L.A. the old guy disappeared. I guess he died. My parents separated and they came to see me on rare occasions. My mother came when she was drunk. My father always brought money, and every now and then he’d spend the night. When he came I’d want to reach him, try to say something to him to get some affection, but he was so closed off there was no way to get through. I admired him, and I thought of him as being a real man’s man. And I really loved him.

My father was trim, real trim. He had a slender, swimmer’s body. He had blue eyes, blonde hair. He had a cleft in his chin. He had a halting, faltering voice, but pleasant sounding, and a way about him that commanded respect. He’d been a union organizer and a strike leader on the waterfront, and he had a bearing. People listened to him. I nicknamed him “Moses” because I felt he had that stature, that strength, and soon everybody in the family was calling him that.

My father was tall, he was strong, and I felt he thought I was a sissy or something. I abhorred violence, but in order to try to win his love I’d go to school and purposely start fights. I fought like a madman so I could tell him about it and show him if I had a black eye or a cut lip, so he would like me. And when I got a cut or a scrape in these fights I would continue to press it and break it open so that on whatever day he came it would still be bad. But it seemed like the things he wanted me to do I just couldn’t do. Sometimes he’d come when I was eating. My grandmother cooked a lot of vegetables, things I couldn’t stand—spinach, cauliflower, beets, parsnips. And he’d come and sit across from me in this little wooden breakfast nook, and my grandmother would tell me to eat this stuff, and I wouldn’t eat it, couldn’t eat it. He’d say, “Eat it!” My grandmother would say, “Don’t be a baby!” He’d say, “Eat it! You gotta eat it to grow up and be strong!” That made me feel like a real weak-ling, so I’d put it in my mouth and then gag at the table and vomit into my plate. And my dad was able, in one motion, to unbuckle his belt and pull it out of the rungs, and he’d hit me across the table with the belt. It got to the point where I couldn’t eat anything at all like that without gagging, and he’d just keep hitting at me and hitting the wooden wall behind me.

My mother was going with some guy named Sandy; he played guitar, one of those cowboy drunkards that runs around and fights. I was going to grammar school and I remember once she came when I was eating lunch in the school yard. She went to the other side of the fence and called me. She was wearing a coat with a fur collar. I was scared because my father had told me, “Don’t have anything to do with her! She didn’t want you to be born! She tried to kill you! She doesn’t love you! I love you! I take care of you!” But he didn’t act like he loved me. I left the yard, and she took me in a car. I said, “I can’t go with you.” But she took me anyway. She smelled of alcohol and cigarettes and perfume and this fur collar, and she was hugging me and smothering me and crying. She took me to a house and everybody was drunk. I tried to get away, but they wouldn’t let me leave. She kept me there all night.

When I was nine or ten my dad took me to a movie in San Pedro: The Mark of the Vampire. It was the most horrible thing I’d ever seen. It was fascinating. There was a woman vampire, all in white, flowing white robes, a beautiful gown, and she walked through the night. It was foggy, and it reminded me of the clouds. In the movie, whoever was the victim would be in-side a house. The camera looked out a window and there was the vampire: there she would be walking toward the window.

I had a bedroom at the back of my grandmother’s house, and my window looked out on the backyard. There was an alley and an empty lot. After this movie, whenever I got ready for bed, I could feel the presence of someone coming to my window. I would envision this woman walking toward me. I started having nightmares. She had a perfect face, but she was so beautiful she was terrifying—white, white skin, and her eyes were black, and she had long, flowing, black hair. She wore a white, nightgownish, wispy thing. Her lips were red and she had two long fangs. Her fingers were long and beautiful, and she held them out in front of her, and she had long nails. Blood dripped from her nails and from her mouth and from the two long fangs. It seemed she sought me out from everyone else. There was no way I could escape her gaze. I’d scream and wake up and run to my grandmother’s room and ask her if I could get in bed with her, and she’d say, “Don’t be silly! Don’t be a baby! Go back to bed!”

This went on and on. I’d have nightmares and wake up screaming. Finally my grandmother told my dad and he took me to a doctor. The doctor gave me some pills to relax me, and it went away. But I kept having the fears. If I went to open a closet door I’d be scared to death. If I went walking at nighttime I’d see things in the bushes.

I’d wander around alone, and it seemed that the wind was always blowing and I was always cold. San Pedro is by the ocean, and we lived right next to Fort MacArthur. Maybe during the First World War there was a lot of action there, but around 1935 it was just a very big place staffed by a few soldiers. It was on a hill, and you could see the ocean all around, and there was a lot of fog and a lot of weeds and trees and brush and old barbed wire, and there was a large area that had been at one time, I think, a big oil field. They had huge oil tanks that went down into the ground very deep, overgrown with weeds. I used to go through the fence and wander around the fort. I’d climb down into these oil things.

Closer to the water they had big guns, disappearing guns, set in cement and steel housings. Every now and then they’d fire them to test them, and they’d raise up out of the ground. But most of the time they were quiet, and I’d sneak around and climb down onto the guns. Down below they had giant railroad guns, cannons, and anti-aircraft guns that they’d practice on; you could feel them going off.

On weekends I’d walk down the hill to a place called Navy Field, where there were four old football fields with old stands. The navy ships docked in the harbor, and the sailors had games, maybe four games going at once. I’d go down alone and sit alone in the stands and watch. Once I was walking under the stands to get out of the wind, and I looked up and saw the people. And the women, when they stood up, you could see under their dresses. That really excited me, so I started doing that, walking around under the stands on purpose to look up the women’s dresses.

I built up my own play world. I loved sports, and I’d play I was a boxer or a football player. I even invented a baseball game I could play alone with dice, but boxing was the one I really got carried away with. At that time Joe Louis was coming up as a heavyweight. I would go out in the garage and pretend I was a fighter. I had a little box I sat on. I’d hear an imaginary bell and get up in this old garage and fight, and it was actually as if I was in the ring. Sometimes I’d get hit and fall down and be stunned, and I’d hear the referee counting, and I’d get up at the last minute, and just when everybody thought I was beaten I’d catch my opponent with a left hook. And then I’d have him against the ropes. I’d knock him out, and everybody would scream and throw money into the ring and holler for me, and I’d hold my hands together and wave to the crowd.

I played by myself for a long time and then, much as I hated to be with other kids, because I felt I wasn’t like them, they wouldn’t like me, I wanted to play sports so bad I overcame that and started playing in empty lots, and I was extremely good at sports. I was good in school, too. My drafting teacher in junior high said I really had a talent, and my father dreamed that one day he’d send me to Cal Tech here or Carnegie Tech back east so I could do something in mathematics or engineering.

My mother’s side of the family was very musical. Her aunt and uncle—I think their last name was Bartolomuccio, shortened to Bartold—had five children. They all played musical instruments. The youngest boy was Gabriel Bartold, and as a child he played on the radio, a full-sized trumpet. He’d put it on a table and stand up to it and blow it.

The Bartolds lived in San Gabriel in a big house. In the back they had a lath-house, an eating place with a big round table. I remember going there several times and all the activity in the kitchen with the aunts and I don’t know who-all making pasta; they made the most fantastic food imaginable. The men drank their homemade wine and ate and ate and ate, and the children were very attentive to the adults. I was very young, and the only thing I really remember is the daughter who was an opera singer. I remember hearing her sing and how pretty she was. She looked like a little angel, and she sang so beautifully with the operatic soprano voice.

I loved music, and when I passed a music store and saw the horns glittering in the window I’d want to go inside and touch them. It seemed unbelievable to me that anybody could actually play them. Finally I told my dad I just had to have a musical instrument. I wanted to play trumpet like my cousin Gabriel. My dad agreed to get somebody to come out and see what was happening with me. He found this man somewhere, Leroy Parry, who taught saxophone and clarinet, and brought him out to the house. In playing football I had chipped my teeth. Mr. Parry looked at my mouth and said I would never be able to play trumpet well because my teeth weren’t strong. He said, “Why don’t you play clarinet? You’d be excellent on clarinet. Give it a try.” I still wanted to play trumpet, but I figured I’d better take advantage of what I had, so I started lessons on clarinet when I was nine years old.

Mr. Parry didn’t play very well, but he was a nice guy, short and plump with a cherubic face, warm, happy-go-lucky. He had sparkling little eyes. You could never imagine him doing anything wrong or nasty or unpleasant. He invited me to his house for dinner a couple of times and I met his wife. She li...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Contributors

- Epigraph

- Cast of Characters

- Part 1 1925–1954

- Part 2 1954–1966

- Part 3 1966–1978

- Conclusion

- Afterword

- Discography by Todd Selbert

- Index