eBook - ePub

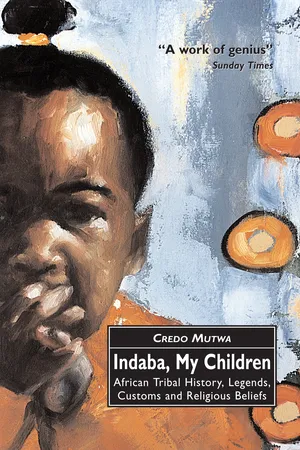

Indaba, My Children: African Tribal History, Legends, Customs And Religious Beliefs

- 720 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Indaba, My Children: African Tribal History, Legends, Customs And Religious Beliefs

About this book

First published in 1964, Indaba, My Children is an internationally acclaimed collection of African folk tales that chart the story of African tribal life since the time of the Phoenicians. It is these stories that have shaped Africa as we know it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Indaba, My Children: African Tribal History, Legends, Customs And Religious Beliefs by Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Book Three

The Journey to ‘Asazi’

IN MY WEB – A DEAD FLY

The land was a thing of incredible beauty, a jewel under the eyes of Ilanga, the God of Day. The land rejoiced in the green and scented embrace of the Maiden Spring and fiercely responded to her tender caresses, like an old wrinkled chief whose cold and tired veins are briefly heated by a kiss from his youngest concubine. The wild beauty of the untamed forest on that glorious day dazzled the eyes. Souls were lost in the misty valleys of happiness.

Each tree and bush was like a bride in full wedding regalia, a bride beautiful and soothing to the beholder’s eye. Thick on each branch was a fresh green scented foliage that spoke of quantities of moisture yielded by a willing soil. Wild flowers laughed amongst the frolicking grass, nourished by the rotten leaves of yesteryear.

Birds argued in the tall trees while hares and steenbuck gambolled in the scented grass, rejoicing in the gentle heat and the perfumed whispering breeze of young summer.

And lo, along one of the footpaths leading into the cool shady depths of the deep forest there came a young man and a young woman. The man was tall, with the wide shoulders and narrow hips of a warrior, and the long legs of a very fast runner. He had a long face that ended in a square cleft chin, the kind which the Wise Ones of the Tribes call the ‘chin of courage’. Under the flat nose with its large flaring nostrils was a mouth forever set in hard lines of fierce determination, while above, his forehead towered high like a cliff above two springs of sparkling water.

Around his head this young man wore a broad band of leopard skin with two feathers tucked in it: one the long tail-feather of an Isakabuli; the other that of a flamingo. The first denoted his royal birth and the second identified him as the son of the Second High Wife of the Chief. A triple necklace of lion’s claws and cowrie shells graced his shoulders while around his manly loins he wore two aprons of cow-skin – one in front and one behind.

The front apron was fringed with long monkey and civet cat tails. On both his forearms he wore heavy bronze ‘warrior bracelets’, so broad they looked more like arm guards. Around his calves he wore leggings of cow-tails which fluffed ever so slightly in the breeze.

He carried a black war shield with a civet cat skin tuft on its long centre stick and he was armed with two heavy hurling assegais and a weighty battle axe. He walked a few paces ahead of the girl with the lithe grace of a stalking beast of prey. His nostrils were dilated and his ears alert for the slightest sound. Haaaieee! Here was a budding warrior, a hunter still in tender flower, a future leader of men. Here was a man born to command! Brave and utterly reckless was the son of Malandela, the High Chief of the Nguni division of the mighty Mambo nation. Brave, reckless and utterly stubborn was the handsome young man Zwangezwi – the Voice of Battle, the last surviving son of the High Chief of the Land, successor to the chieftainship of the Nguni limb of the Mambo people!

And ewu, ha-la-la! Now we come to the girl, the foreign ebony black girl who was not of the Mambo people, but belonged to a tribe which was once great and which had been reduced to only a few thousand people through wars. This tribe which was now in danger of becoming absorbed by the Mambo . . . unless . . .

This girl was tall and slender, with long legs and with breasts jutting fircely from her chest. But she was the kind of girl whom chiefs forbid to bear children because, although her buttocks were beautifully shaped, her hips were far too narrow. She was beautiful. Yea-ha, she reminded one of a skilfully carved image from the land of Tanga-Nyika; she was a beautiful image carved in living ebony. Her face was oval and her forehead round and smooth. Her nose was tiny and flat, with small nostrils, and her full, wholesome mouth had a lower lip slightly more prominent than the upper. Her neck, graced by a broad band of flaming red copper, was a column of live ebony.

Whereas the Nguni maidens of her age either wore fringed mutshas, short skin shirts, or just nothing at all, this foreign girl wore something which no Nguni female would ever wear – a soft tiger-cat loinskin. Save for large copper earrings that weighted down her pierced earlobes and the band around her neck, she wore no other ornaments.

One could tell at first glance that this girl was very uneasy, that her soul was a canoe floundering in the whirlpool of fear and great anxiety. Nervous were the glances that she cast about her and she paused now and again to wring her hands and to open her mouth as if to speak to the young man in front of her, and then to shut it with a silent sob. The dew of tears hung heavy on her long eyelashes and the spirit of dread and guilt was heavy on her knees. Suddenly the man’s voice shattered her troubled thoughts with a loud ‘Aieeee! Look over there . . . over there Mulinda, look!’

The girl’s tear-misted and half-closed eyes slowly opened wider and followed the young man’s pointed finger. They saw what is one of the most terrible omens of naked evil that anyone can experience. A mighty eagle had dived out of the blue skies into a grassy glade to their left, and now it was rising again into the heavens with a young steenbuck clutched in cruel talons. The keen eyes of the young Prince followed the eagle into the distance until it was but a speck above the hazy forest. Then he turned to Mulinda and she saw that his handsome features were clouded with uneasiness.

‘That was an evil thing we saw, Oh Mulinda,’ he said, ‘for do not the Wise Ones say that to see an eagle snatching an animal off the ground is an omen of death to all those who see it?’

‘It is so, my Prince,’ agreed the girl. ‘We must turn back and go home.’

‘No!’ cried Zwangezwi, the son of Malandela, fiercely. ‘We have come so far and cannot turn back now. You will not escape so easily from giving me what you were told to give me, Oh daughter of the Vamangwe.’

The son of Malandela and the Vamangwe girl were going far away from their homes to break a law. They were going deeper and deeper into the dangerous forest to find a quiet place in which to break one of the oldest tribal laws, the High Law which says that no young man under the age of twenty-five must take a girl to the love-mat; and that no young man should as much as kiss a girl unless he is first circumcised and initiated into manhood in accordance with the High Laws and Customs of the Tribes.

Zwangezwi was only twenty years of age and he thought that five years was far too long a time to wait before he was initiated and permitted to enjoy the doubtful privileges of manhood. He was very tired of sitting near the crackling fire at night and listening to lurid, in fact, very exaggerated accounts by older warriors of what they do to their lovers. Zwangezwi was firm in his belief that akuko okwedlula uku zibonela wena (nothing beats having seen and experienced something yourself). He was firm in his resolve to have personal experience of what he had heard so much about. But the young man should have remembered another old saying that ukutanda Ukwazi izim fihlo ezingalingani nawe ikona okwemuka u nogwaja umsila wa khe (it was curiosity that shortened the rabbit’s tail – or, more literally, the desire to know secrets that are above you is the thing that deprived the rabbit of his tail).

At last they came to a grassy clearing above which towered a huge outcrop of rock with a large cave at its base, a cave which Zwangezwi knew very well and within which he had sheltered many times with his father’s warriors when they were out on a hunt and caught in a thunderstorm. It was in this cave that Zwangezwi had played with his half-brothers Vivimpi and Bekizwe only three summers ago before both the elder boys were drowned in a canoe accident a year later. Inside the cave were many paintings of animals and men, painted by the Little Yellow Ones, the Bushmen, years and years ago. Some of the human figures were done in white, representing the mysterious race called the Strange Ones – a race of White men who held the Black Tribes in slavery for hundreds of years. It was to this cave, full of memories of the past, that Zwangezwi led the Vamangwe girl Mulinda, and there he unrolled the leopard skin he had been carrying behind his shield and spread it on the sandy floor. He pulled the girl down beside him. To his great surprise he found she was crying and shaking all over like a sapling in a storm.

‘Hau!’ he exclaimed. ‘What is the matter, Oh Mulinda? Why are you crying like a scolded child?’

‘My Prince,’ she sobbed, ‘let us go from here.’

‘Why girl? Did not your brother Vamba tell you to come here with me? Did he not promise to keep our secret and let no-one know about what we are going to do?’

‘He did,’ she wept. ‘But it is not . . . you see . . . Vamba is not what he seems to be . . . he is your father’s . . .’ Her voice broke and her sobs were loud in the dark brooding interior of the cave.

‘He is my father’s what?’ demanded the young man.

‘Vamba, my brother, is your father’s . . . great enemy!’

‘Aieee! That is a lot of nonsense Mulinda. Vamba is my closest and dearest friend and he is my father’s best witchdoctor. He even saved me from a wounded warthog only last year. He is the most trustworthy counsellor my father has and he is more loyal to my father than all his Nguni Indunas put together. How dare you call your own brother my father’s enemy?’

‘Believe me, Prince, believe . . .’

‘Ahhhhh!’ laughed Zwangezwi. ‘So Malangabi, my old friend, was right when he said that you women start talking a lot of nonsense when you are on fire with desire. You are ablaze with the great longing for me, Oh my stolen love, so you have begun to talk all sorts of nonsense. Now, now, come to me and let me put the fire out.’ So saying, he seized the girl roughly by the shoulders and all but wiped her lips off her face in one great clumsy kiss. Then he remembered what his old friend the rascally Induna, veteran Malangabi, always told him that he should do when one day he got an intombi in his arms. He started showering the girl’s lips, neck and breasts under a rain of what he fondly thought were kisses. He proceeded to caress her with rather clumsy heavy-handed, self-conscious movements of his unsteady, calloused hands until at last, more by nature than from anything he did, Mulinda became so heated that she drew him to her with a short sob . . .

Eventually Zwangezwi released the limp form of the girl and sat up, dazed, shocked, and very thoroughly frightened. His head was swimming and he felt like vomiting . . . but most of all he felt like leaping to his feet and running for dear life. ‘Why . . .’ he thought, ‘why, I never thought it felt like this . . . I wish it had not happened . . . I . . . I am so scared, so ashamed . . . I . . .’ Then he remembered an old tribal saying: Labo abazama ukuwela umfula Wo tando bese bancane badibana ne zimanga nga pesheya (they who cross the river of love while still young will always meet very nasty surprises beyond it).

Zwangezwi was soon regretting his boyish curiosity. He began to feel very tired and in spite of his valiant efforts to keep his eyes open he slipped away into the valley of sleep in broad daylight – which is a very shameful thing indeed to happen to a warrior.

He was roughly awakened by the girl, whose voice was edged with fear and horror. ‘My Prince, four times have I tried to awaken you. Wake up, for your mother’s sake, wake up . . . they are coming to kill you!’

Although still dazed, the young man seized his two spears as a tall figure loomed in the entrance of the cave – a featureless silhouette against the blazing silver sky. Instinctively and with deadly accuracy, Prince Zwangezwi hurled his first spear and had the satisfaction of hearing it thud home into the armed intruder’s chest.

A group of figures, all heavily armed, suddenly burst into view as the first man sagged to his knees. A hail of spears ripped into the chest and belly of the young Prince even as he raised his arm to throw his second spear. Zwangezwi fell backwards, treacherously and mortally wounded, but no cry escaped his lips. The son of Malandela was too brave to cry out when struck down by lowborn and cowardly curs.

As his murderers trooped into the cave a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Character Cast

- Prologue

- Introduction

- Book One: The Bud Slowly Opens

- Book Two: Stand Forever, Oh Zima-Mbje

- Book Three: The Journey to Asazi

- Book Four: Yena Lo! My Africa

- Glossary