- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Every letter contains a miniature story, and here are some of the greatest. From Oscar Wilde's unconventional method of using the mail to cycling enthusiast Reginald Bray's quest to post himself, Simon Garfield uncovers a host of stories that capture the enchantment of this irreplaceable art (with a supporting cast including Pliny the Younger, Ted Hughes, Virginia Woolf, Napoleon Bonaparte, Lewis Carroll, Jane Austen, David Foster Wallace and the Little Red-Haired Girl). There is also a brief history of the letter-writing guide, with instructions on when and when not to send fish as a wedding gift. And as these accounts unfold, so does the tale of a compelling wartime correspondence that shows how the simplest of letters can change the course of a life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To the Letter by Simon Garfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Magic of Letters

Lot 512. Walker (Val. A.) An extensive correspondence addressed to Bayard Grimshaw, 1941 and 1967–1969, comprising 37 autograph letters, signed, and 21 typed letters, with a long description of Houdini: ‘His water torture cell simply underestimated the intelligence of the onlooker, no problem to layman & magician alike,’ describing a stage performance by him where Walker was one of the people called on to attach handcuffs, and another at which he fixed Houdini in his own jacket, continuing with information about his own straight jacket, his ‘Tank in the Thames’ and ‘Aquamarine Girl’ escapes, and other escapology, including a handbill advertising ‘The Challenge Handcuff Act’, and promotional sheet for George Grimmond’s ‘Triple Box Escape’.

est. £300 – £400

Bloomsbury Auctions is not in Bloomsbury but in a road off Regent Street, and since its inception in 1983 it has specialised in sales of books and the visual arts. Occasionally these visual arts include conjuring, a catch-all heading that offers a glimpse into a vanishing world, and many other vanishing items besides, as well as sleight-of-hand, mind-reading, contortionism, levitation, escapology and sawing.

On 20 September 2012 one such sale offered complete tricks, props, solutions for tricks and the construction of props, posters, flyers, contracts and letters. Several lots related to particular magicians, such as Vonetta, the Mistress of Mystery, one of the few successful female illusionists and a major draw in Scotland, where she was celebrated not only for her magic but also for her prowess as a quick-change artiste. There was one lot connected with Ali Bongo, including letters describing seventeen inventions, and, improbably, ‘a costume description for an appearance as The Invisible Man’.

There were three lots devoted to Chung Ling Soo, whose real name was William E. Robinson, born in 1861 not in Peking but in New York City (the photographs on offer suggested he looked less like an enigmatic man from the East and more like Nick Hornby with a hat on). One of the letters for sale discussed Chung Ling Soo’s rival, Ching Ling Foo, who claimed that Chung Ling Soo stole not only the basics of his name, but also the basis of his act; their feud reached its apotheosis in 1905, when both Soo and Foo were performing in London at the same time, and each expressed the sort of inscrutable fury that did neither of them any harm at the box office. In order to cultivate his persona, Chung Ling Soo never spoke during his act, which included breathing smoke and catching fish from the air.

Between 1901 and 1918 Soo played the Swansea Empire, the Olympia Shoreditch, the Camberwell Palace, the Ard-wick Green Empire and Preston Royal Hippodrome, but his career met an unforgettable end onstage at the Wood Green Empire – possibly the result of a curse laid by Ching Ling Foo – when his famous ‘catch a bullet in the teeth’ trick didn’t quite work out as hoped. On this occasion, his gun fired a real bullet rather than just a blank charge, and, as historians of Soo are quick to point out, his first words on stage were also necessarily his last: ‘Something’s happened – lower the curtain!’ Among the lots at the Bloomsbury sale were letters from assistants and friends of Soo claiming he had been born in Birmingham, England, at the back of the Fox Hotel, and that the death may not have been an accident. ‘We who knew Robinson,’ wrote a man called Harry Bosworth, ‘say he was murdered.’

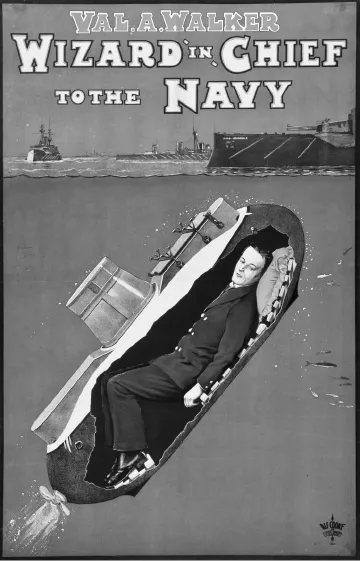

But the stand-out lot was the one involving the Radium Girl, the Aquamarine Girl, Carmo & the Vanishing Lion, Walking Through a Wall and the origins of sawing thin female assistants – the items relating to the life of Val Walker. Walker, who took the name Valentine because he was born on 14 February 1890, was once a star performer. He was known as ‘The Wizard of the Navy’ for his ability to escape a locked metal tank submerged in water during the First World War (a feat later repeated in the Thames in 1920, witnessed by police and military departments and 300 members of the press). After drying himself he received offers to perform all over the world. He subsequently escaped from jails in Argentina, Brazil, and, according to information contained in the auction lot, ‘various prisons in Spain’.

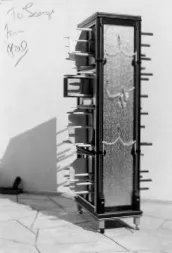

Walker was the David Copperfield and David Blaine of his day. He appeared in shows at Maskelyne’s Theatre of Mystery, next door to BBC Broadcasting House, the most famous European magic theatre of the time (perhaps of all time), surprising audiences with swift escapes from manacles, straitjackets and a 9-foot-long submarine submerged in a glass-fronted tank at the centre of the stage. And then there was the trick with which Walker secured his place in magical history: Radium Girl. This was known as a ‘big box’ restoration illusion, a process in which a skilled woman enters a cabinet and is either sawn in half or penetrated with swords, and then somehow emerges unscathed. Walker’s role in this trick is fundamental; he is believed to have invented it in 1919, building the box himself and devising the necessary diversions and patter to make it the climax of his show.

The trick is one we’ve seen on stage or television for 95 years: an empty box on casters is displayed to the audience, its sides and base are banged, an assistant climbs in and is secured by chains, the door is closed, knives or poles are inserted into pre-drilled holes, followed by sheets of metal that seem to slice the woman into three parts (feminists have consistently placed this trick in their Top Five). Weaned on cynicism and trick photography, we have become blasé about such things today, but Radium Girl was once quite something. The sheets and poles and swords are then (of course) all pulled out, the door is opened and the chains removed, and the woman is smiling and whole.

Britain’s secret weapon: Val Walker contemplates his escape.

The Radium Girl illusion.

But then something even more dramatic happened: Walker got bored. He grew tired of the touring. He became envious of the acclaim and riches poured upon those he considered lesser talents, among them Harry Houdini. So one day Walker just quit. His professional disappearing act was, as might only be expected, an impressive feat: he gave up his Magic Circle membership in 1924, resumed his work as an electrical engineer, moved to Canford Cliffs, a suburb of Poole in Dorset with his wife Ethel, had a son named Kevin, and was never seen on a stage again. His gain, one imagines, but magic’s loss.

At the end of September 1968, several decades after he retired from magic, Walker made one final appearance at a convention in Weymouth. But he came as a fan, not a star, and he had a particular purpose for being there, to see the Radium Girl performed one more time. The magician was a man called Jeff Atkins, and Walker had rebuilt a new cabinet especially for him that summer in his garden. And it really was a last hurrah: Walker died six months later of a chronic and progressive disease (probably cancer), and many of his secrets went with him.

But not all: some of his letters remain, and are the source for much of the material you have just read, gleaned from browsing the files at Bloomsbury Auctions the day before the sale. His letters provide news of his great entertainments, but of a personal life that appears to have been conducted with modesty and decorum and a great care for others (until the end, as we shall see).

The more I read them, the more I wanted to know. Within a couple of days – from seeing the mention of Walker in the sale catalogue online, to skimming through these remnants of his life at the auction preview – I had fallen under the spell of a man I had never previously heard of. And I had become enveloped by a word he used more than once in his letters, his milieu, a world that relied for its buoyancy on deception, apparition and secrecy. But now the letters were letting me in.

Val Walker’s correspondence, both inconsequential and profound, was doing what correspondence has so alluringly, convincingly and reliably done for more than 2,000 years, embracing the reader with a disarming blend of confession and emotion, and (for I had no reason to suspect otherwise, despite the illusory subject matter) integrity. His letters had secured what his former spiritualist medium colleagues could not – a new friend from beyond the grave. The folders now at auction not only prised open a subculture that was growing ever more clandestine with the cloaky passage of time, but presented a trove of incidental personal details that, in other circumstances, would have bordered on intrusion. I sat in that auction room and wondered: what else could bring back a world and an individual’s role within it so directly, so intensely, so plainly and so irresistibly? Only letters.

Letters have the power to grant us a larger life. They reveal motivation and deepen understanding. They are evidential. They change lives, and they rewire history. The world once used to run upon their transmission – the lubricant of human interaction and the freefall of ideas, the silent conduit of the worthy and the incidental, the time we were coming for dinner, the account of our marvellous day, the weightiest joys and sorrows of love. It must have seemed impossible that their worth would ever be taken for granted or swept aside. A world without letters would surely be a world without oxygen.

This is a book about a world without letters, or at least this possibility. It is a book about what we have lost by replacing letters with email – the post, the envelope, a pen, a slower cerebral whirring, the use of the whole of our hands and not just the tips of our fingers. It is a celebration of what has gone before, and the value we place on literacy, good thinking and thinking ahead. I wonder if it is not also a book about kindness.

The digitisation of communication has effected dramatic changes in our lives, but the impact on letter-writing – so gradual and so fundamental – has slipped by like an English summer. Something that has been crucial to our economic and emotional well-being since ancient Greece has been slowly evaporating for two decades, and in two more the licking of a stamp will seem as antiquated to a future generation as the paddle steamer. You can still travel by paddle steamer, and you can still send a letter, but why would you want to when the alternatives are so much faster and more convenient? This book is an attempt to provide a positive answer.

This is not an anti-email book (what would be the point?). It is not an anti-progress book, for that could have been written at the advent of the telegraph or the landline phone, neither of which did for letter-writing in the way that was predicted, certainly not in the way email has done. The book is driven by a simple thing: the sound – and I’m still struggling to define it, that thin blue wisp of an airmail, the showy heft of an invitation with RSVP card, the happy sneeze of a thankyou note – that the letter makes when it drops onto a doormat. Auden had it right – the romance of the mail and the news it brings, the transformative possibilities of the post – only the landing of a letter beckons us with ever-renewable faith. The inbox versus the shoebox; only one will be treasured, hoarded, moved when we move or will be forgotten to be found after us. Should our personal history, the proof of our emotional existence, reside in a Cloud server (a steel-lined warehouse) on some American plain, or should it reside where it has always done, scattered amongst our physical possessions? That emails are harder to archive while retaining a pixellated durability is a paradox that we are just beginning to grapple with. But will we ever glow when we open an email folder? Emails are a poke, but letters are a caress, and letters stick around to be newly discovered.

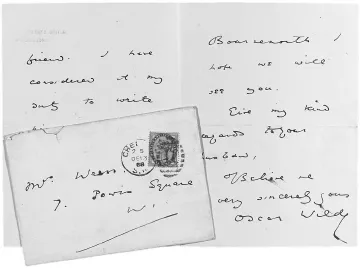

A story is told of Oscar Wilde: he would write a letter at his Chelsea home in Tite Street (or, looking at his handwriting, ‘dash off’ is probably more accurate), and because he was so brilliant and so busy being brilliant, he wouldn’t bother to mail it. Instead, he would attach a stamp and throw the letter out of the window. He would be as certain as he could be that someone passing would see the letter, assume it had been dropped by accident, and put it into the nearest letterbox. If we all did this it wouldn’t really work, but only people like Wilde had the nonchalant faith. How many letters didn’t reach the letterbox and the intended recipient we will never know, but we can be fairly sure that if the method didn’t work well, or if too many were neglected because they landed in manure, Wilde would have stopped doing it. And there are a lot of letters from Tite Street and elsewhere that have survived him to reach handy auction prices. There’s no proper moral to this story, but it does conjure up a rather vivid picture of late-Victorian London: the horse-drawn traffic on the cobbled street below, the bustle, the clatter and the chat, and someone, probably wearing a hat, picking up a letter and doing the right thing, because going to the postbox was what one did as part of life’s daily conversation.*

There is an intrinsic integrity about letters that is lacking from other forms of written communication. Some of this has to do with the application of hand to paper, or the rolling of the paper through the typewriter, the effort to get things right first time, the perceptive gathering of purpose. But I think it also has something to do with the mode of transmission, the knowledge of what happens to the letter when sealed. We know where to post it, roughly when it will be collected, the fact that it will be dumped from a bag, sorted, delivered to a van, train or similar, and then the same thing the other end in reverse. We have no idea about where email goes when we hit send. We couldn’t track the journey even if we cared to; in the end, it’s just another vanishing. No one in a stinky brown work coat wearily answers the phone at the dead email office. If it doesn’t arrive we just send it again. But it almost always arrives, with no essence of human journey at all. The ethereal carrier is anonymous and odourless, and carries neither postmark nor scuff nor crease. The woman goes into a box and emerges unblemished. The toil has gone, and with it some of the rewards.

Oscar Wilde writes to Mrs Wren in 1888.

I wanted to write a book about those rewards. It would include a glimpse of some of the great correspondents and correspondences of the past, fold in a little history of mail, consider how we value, collect and archive letters in our lives, and look at how we were once firmly instructed to write such things. And I was keen to encounter those who felt similarly enthused about letters, some of them so much so that they were trying to bring letters back. I was concerned primarily with personal letters rather than business correspondence or official post, though these two may reveal plenty about our lives. The letters in this book are the sort that may quicken the heart, the sort that may often reflect, in Auden’s much loved words, joy from the girl and the boy. I had no ambitions to write a complete history of letter-writing, and I certainly wouldn’t attempt a definitive collection of great letters (the world is too old to accommodate such a thing, and lacks adequate shelving; it would be akin to collecting all the world’s art in one gallery), but I did want to applaud some of the letters that managed to achieve a similarly gargantuan task – the art of capturing a whol...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1 The Magic of Letters

- 2 From Vindolanda, Greetings

- 3 The Consolations of Cicero, Seneca and Pliny the Younger

- 4 Love in Its Earliest Forms

- 5 How to Write the Perfect Letter, Part 1

- 6 Neither Snow nor Rain nor the Flatness of Norfolk

- 7 How to Write the Perfect Letter, Part 2

- 8 Letters for Sale

- 9 Why Jane Austen’s Letters Are so Dull (and Other Postal Problems Solved)

- 10 A Letter Feels Like Immortality

- 11 How to Write the Perfect Letter, Part 3

- 12 More Letters for Sale

- 13 Love in Its Later Forms

- 14 The Modern Master

- 15 Inbox

- Epilogue: Dear Reader

- Acknowledgements

- Select Bibliography

- Picture Credits

- Permisions Credits

- Index

- My Dear Bessie: A Preview