- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

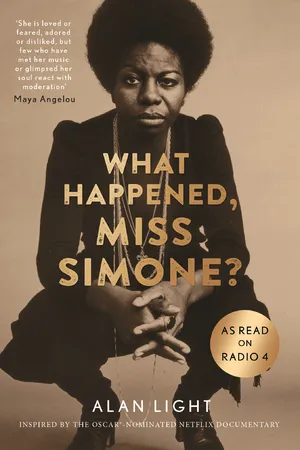

'From her raging, handwritten letters to late-night phone calls with David Bowie, this biography gets up close and personal with the tempestuous Nina Simone' Observer

Drawing on glimpses into previously unseen diaries, rare interviews and childhood journals, and with the aid of her daughter, What Happened, Miss Simone? tells the story of the classically trained pianist who became a soul legend, a committed civil rights activist and one of the most influential, provocative and least understood artists of our time.

This is the story of the real Miss Simone.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What Happened, Miss Simone? by Alan Light in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

I was born a child prodigy, darling. I was born a genius.

Nina Simone was born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in Tryon, North Carolina, on February 21, 1933, the sixth of eight children. The Waymon family was rounded out by sisters Lucille, Dorothy, and Frances and brothers John Irvin, Carrol, Harold, and Sam. Perhaps foreshadowing the instability that would go on to define much of her life, her father, John Divine Waymon, worked various odd jobs, never sticking with one craft for too long; mother Mary Kate was the granddaughter of slaves and came from a family of preachers (fifteen of them in all, according to Simone). She carried on that storied tradition and became a traveling Methodist minister, supplementing the spare income with cleaning and domestic work.

Tryon was a resort town, which created—superficially, at least—a more liberal racial atmosphere than in most of the South. “It was not as rigidly segregated as other towns,” said Carrol Waymon, who would later become an educator and activist, forming the Africana Studies Program at San Diego State University. Black neighborhoods scattered through Tryon. This also meant that black people interacted more frequently with white people than they might in other places, playing sports together and working at the resort.

Still, there was only so far such contact could go. “One of my brothers’ friends who must have been, I don’t know, nineteen, seventeen, something, it was found that he was going with one of the white girls,” said Carrol. “It was hush-hush, I didn’t know about it. He had to get out of town one night, so we went, ‘Why did he leave so soon?’ I began to understand he was not supposed to be going with whites.”

By Carrol’s count, the Waymons lived in about seven different houses in the area. Frances, the youngest, described one of the residences as “a wooden house that was not much to be desired”—very old, with a brick stove, an outhouse, no insulation, and a porch that had been enclosed to serve as an extra bedroom.

“You went out and you brought in buckets of water,” she said. “We had big round tin tubs, they call them. You heated the water on the wooden stove, that’s how you took your Saturday night bath. It was such an ordeal that everybody took baths on Saturday night. And we had a garden, we had pigs and cows and chickens. We were very poor.”

Despite the family’s poverty, Nina Simone’s earliest images of her childhood were pleasant enough. “My first conscious memory of my mother is her singing while she cooks, while she washed clothes,” she said. “She was always cheerful. We had a farm, a little bitsy one. Momma used to churn buttermilk on an old-fashioned churn and she showed me how to do it.

“Most of all I remember being with the other kids. Momma would cook for us, and sometimes she would say, ‘I don’t know where I’m going to get dinner.’ Sometimes we didn’t have much to eat and she would pray, and then by the time evening came on, we’d have enough food.”

To stretch the rations and feed her family of ten, Mary Kate would make what she called “Waymon Specials”—dumplings or a concoction called vinegar pie. She canned fruits and vegetables to eat during the winter. “Momma never seemed to worry about being poor or hungry,” Simone said. “We weren’t ever hungry ’cause Momma knew how to not do that. It is true we were very poor, but we didn’t feel the poverty because of the way she did things.”

The singer’s first recollections of her father were also charmingly bucolic. More approachable than her mother, he was lighthearted, even mischievous, and he and Eunice had a genuine intimacy, a special bond. “My daddy putting me on his knee, rocking me to patty-cake, my dad playing with me—I was his pet,” she said. “He had an old jalopy, a Model A Ford, and that thing used to make all kinds of noises; I could hear him clear across town coming home and I would run up the hill, through the woods, to be there when he crossed that particular spot, to jump on the running board and go home with him. I would do this every day.”

“His whole life was playing,” she said in another instance. “He played at everything. He didn’t tell us any jokes, we were too young. But he was playful, always.”

John Waymon’s flair for entertaining—including his distinctive “double whistle”—was more than just a way to amuse his family and keep their spirits light. In fact, he and Mary Kate had started out performing onstage together. “Daddy loved the ‘St. Louis Blues,’ had his spats, he could dance and sing,” said Carrol. “He’d play his guitar, and he also played the harmonica, he was excellent at that. Had he not met Mother, he would have probably gone on to be on the stage.”

But when Mary Kate started preaching, after they were married, it put an end to his performing career. John worked as a barber, a truck driver; he even started a dry-cleaning business. He had what his daughter Frances described as an entrepreneurial spirit and was a pillar of the church community. As a business owner, he could proudly call himself middle class.

But when the Depression hit, John’s options dwindled. Around 1931, he closed his businesses down and lost his trucks. He took work as a handyman, a caretaker for white families, a cook at a lakeside Boy Scout camp. But by the time Eunice was born, he was mostly working in the garden for sustenance and anything he might sell or trade.

Some of this slowdown, though, might have had more to do with his health than with the country’s dire economic straits. He had a blockage in his small intestine, and in 1936 he had an operation. After the surgery, a rubber tube was inserted into the stomach so it could drain, and the wound needed to be exposed in order to be washed and bathed. And this condition meant that the sole responsibility of supporting the family fell on Mary Kate.

Eunice, age three, was tasked with nursing her father back to health. “I would take him for a walk every day and fix his meals, and I was so happy,” she said. “He loved the heat, and he had these raw eggs that had to be beaten up with a little vanilla and a little sugar, and it tasted so good I used to get a little bit for myself. But I had to feed him this every day and take him for a walk.”

There were additional upheavals during this time, too. During his recovery, the Waymon house burned down in the middle of the night. They moved once, then again to a town called Lynn, where their house was so primitive that not only did it not have indoor plumbing, it didn’t even have an outhouse; the family had to use the woods as the bathroom.

The conditions were so poor that the Waymons left and stayed with a relative back in Tryon, then finally resettled in a house of their own again. Despite this, John hadn’t fully lost his political spirit—serving on the town council, he led a protest against a poll tax and had the law changed—but a decade of illness and financial insecurity was weighing on him.

“He was energetic, active, well accepted, well respected,” said Carrol, “and had to go from being on his way to great things to the bottom economically, and it just knocked him for a loop.”

Whether John’s own problems were a cause or merely an effect, the Waymon family was fracturing. Eldest brother John Irvin fought with his father and left home at sixteen, completely vanishing from the Waymons’ lives for more than ten years. With the advent of World War II, Carrol enlisted in the army.

“There was a lot of conflict between my mother and father, and there was a lot of conflict between Dad and the children,” said Frances. “I never met my oldest brother until some thirty-one years of my life, because he left home because of Dad. My mother was very independent, very strong-willed, very determined. Very strongly committed, very, very religious. She is a pillar of strength, and highly respected.

“I felt like some of the frustration came from the fact that maybe Mom was more dominant. I feel that that added to that frustration, with Dad constantly trying to be respected as the head of the household.”

Simone felt that her father resented his wife’s autonomy and her prominence. “He had more blues than anything,” she said, “because my dad did not like my mother preaching. It was always a rivalry for him. Something that takes her away—he didn’t like it, he never liked it. He finally started preaching himself, became an ordained minister. I think now I look back, he did it to spite Momma.” Not that Simone took his preaching too seriously. “The fact is, I thought it was a joke,” she said.

At the time, though, Simone didn’t feel there was significant strain in her parents’ marriage. They may not have shown much affection for each other, but they didn’t fight, so as far as she was concerned they seemed happy enough.

As a girl, Eunice was proud of her mother’s role as a leader in Tryon. “I loved the way she looked, I loved the way she preached, I loved the way she cooked dinner, when she sang, when she walked,” she said. “I was interested in everything to do with my mother—everything.

“They called her ‘Mother Waymon’ in the community. They’d come to her with their problems and things, and my mom always has someone around who needs her for something. She loves that role. It doesn’t complete her life, but I’ve never heard her complain. Me, I complain all the time.”

But as much as she admired her mother, there was a distance between them, and it would bother her for the rest of her life. Eunice never felt the same kind of intimacy from her mother that she had with her father. “I didn’t get enough love from my mom, did not have no affection,” she said. “I needed to touch. I needed someone to play with me. And everything in the house was serious. There were never any jokes. There were never any games. My mom didn’t allow Chinese checkers, she didn’t allow cards. No dancing, no boogie-woogie playing. Everything was ‘no.’ ”

It was primarily Lucille Waymon, the oldest sister, who took care of the children. She stood in as a sort of surrogate mother while Mary Kate was out on the preaching circuit and provided the maternal affection they were missing.

“My mother never kissed me, she never held me,” Simone said in another interview. “I got that from Lucille. When Lucille got married I cried, ’cause he was taking her away from me. My mother wasn’t my mother—Lucille is my mother, she brought me up.”

There was also constant pressure on the Waymon children. Given their mother’s status and their father’s ambition, it was assumed that they would be high achievers, shining examples who were active in the community. “We were expected to be model kids, because we were preachers’ kids,” said Carrol. “We were supposedly the very epitome of good kids, living lives publicly, real bright. It was expected that we be the brightest in the school and we had that kind of reputation.”

Eunice’s behavior certainly lived up to this high bar, and she was desperate to please her mother. “I never got into any trouble,” she said. “If I got in trouble at all, I’d go downstairs in the basement and cry. All my mother would have to say to me is ‘You did something wrong.’ She never spanked me or anything, all she had to do was say that I did something wrong and I would cry myself to death. If my mother told me to jump in the river, I would have jumped in the river because she said so. I never disobeyed at all. Never.”

All the time she was navigating the complexities of her family life, though, Eunice Waymon had already found the thing that would offer her solace and give her direction. She had, in fact, already begun the path that would determine the rest of her life. From her very first days, the girl who would become Nina Simone had discovered music.

When Eunice was a baby, she saw a page in a magazine. It was an advertisement, with some musical notes on a staff. She looked at the notes and started to sing.

At six months old, she knew what notes on paper actually were. When she was three, a piano arrived at the Waymon household; she recalled playing the spiritual “God Be with You Till We Meet Again,” in the key of F—though she didn’t quite know about keys yet. “I didn’t get interested in music,” she once said. “It was a gift from God ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Discography

- Notes

- Bibliographical Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Illustrations

- Promo page for other Canongate titles