- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Story of Looking

About this book

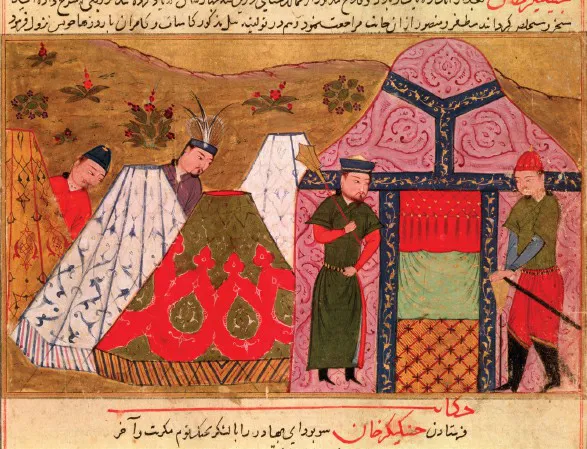

In The Story of Looking, Mark Cousins takes us on a lightning-bright tour – in words and images – through how our looking selves develop over the course of a lifetime, and the ways that looking has changed over the centuries. From great works of art to holiday photos, from cityscapes to cinema, through science and history, protest and propaganda, and the refusal to look, this book illuminates how we construct as well as receive the things we see.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Looking by Mark Cousins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art Theory & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

STARTING

CHAPTER 1

STARTING TO LOOK: FOCUS, SPACE AND COLOUR

‘If I could alter the nature of my being and become a living eye,

I would voluntarily make that exchange.’

I would voluntarily make that exchange.’

– Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Julie, or the New Heloise

FOCUS

We should start where everything started. The Big Bang did not bang. Initially at least, there was no medium through which the sound waves could travel. It could be seen, except there was no one to do the seeing. It was not the Big Bang, it was the Big Flash. The rapid expansion from quantum dimensions 13.8 billion years ago is likely to have produced so much light that the Big Flash was the brightest thing that has ever happened. It made looking possible. The seen began.

Billions of years after the Big Flash, human see-ers began too. They had missed the most visible event in history, but by the time of their arrival life had evolved to a dazzling degree. Humans looked out into the world via two swivelling, vulnerable, aqueous orbs. They were astonished, these eyeballs, and astonishing. In each, 120 million rods were able to assess brightness and darkness in five hundred gradients. Seven million cones would, in time, be able to register a million colour contrasts.

How does the photo album of our life begin? With blank pages. Let’s imagine the birth of an early Homo sapiens in Africa about 200,000 years ago. She lies on her father’s hand, looks out into the world and begins to lay down visual impressions. The baby’s big, absorbent eyes start to live. The first things that register are incomplete. Where the optic nerve attaches to the retina at the back of the eye there is a blind spot, a hole in what it sees, which will be there throughout her life. She has no past, this baby, or so it seems. The baby quickly sees grey blurs. Shadows and outlines fall upon the blank pages. It takes time for life to come into sharp focus for a baby, and before it does, the world looks like this:

Soft-edged. Immaterial. As an adult we have multiple reactions to such an image. It is troubling in that, if we were to walk forward into this landscape above, we would be unable to see if there were holes in the ground, or branches that might stab us in the eye. Lack of focus makes us unsafe, uneasy. But that is not all. In the story of looking, visual softness, lack of focus, light rays meeting in front of or behind our retinas rather than on them, are not necessarily defects. These early impressions were types of imagery that would continue to play a part in how we fear, love, admire and think of ourselves.

To see how, let’s start with this image from Swedish film-maker Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 movie Persona.

A boy looks at his mother. She is in black and white and out of focus, rather like a baby would see its mum. Within minutes of its birth, our early Homo sapiens baby stares at faces – its parents, animals or even simple graphic representations of two eyes, a nose and a mouth. Contained within its genetic information is the ability to discern the arrangement. Its blank pages have ghost images on them, ready to develop.

The boy in the film holds his hand up, to try to touch such a ghost image, or is he trying to wave? He is apart from his mother; locked out of her world, as if a pane of glass separates them. There is distance between them, but the focus seems to contradict that distance. It is as if she is so close that the lenses in our eyes are not strong enough to bend the rays from her face into sharpness. Most of us have experienced waking up in bed beside someone, their head so close to ours that they are a blur; at such short distances, the other person’s two eyes can merge into one large one in the middle of their head, as if they are a Cyclops.

Bergman’s image (filmed by his great cinematographer Sven Nykvist) and the black and white, blurred trees that the baby saw tell us something about the look of love. Lack of focus, especially in close-up, makes us feel adjacent, almost in a force field. It excludes background. This image from the 1929 film The Divine Lady shows how mainstream entertainment, in its desire to depict love, has pushed visual softness to an extreme.

It is as if actor Corinne Griffith is in the fog of love, or has been burnished. This could almost be what a baby sees. Visual softness reduces psychological distance; everything seems to have melted away. The image is not far from abstraction. The reverie of the unfocused. Like our earlier image of the forest, this one is also somewhat unsettling. There is trouble in her eyes, and tears are coming. The visual softness means that we have lost our bearings here, that we are in a realm where everything is close, felt and emotionally flooded. There is helplessness in the visually soft. We do not know which way is up. This image of Corinne Griffith was photographed by John F. Seitz, who would go on to film Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity.

And visual softness is not only about a baby’s first glimpses of the world, our close encounters with a lover, or the visual strategies of romantically photographed cinema. The eyes, smile and background in this next famous image show that painters have used the unfocused too.

In Renaissance Italy, the technique was called sfumato, which its inventor, Leonardo da Vinci, described as the ‘the manner of smoke, or beyond the focus plane’. The portrait was commissioned by the husband of the sitter, Lisa del Giocondo, so, like the picture of Corinne Griffith, it is a look of love image. But it is more than that. Leonardo’s smokescreen reduced the amount of visual information in the landscape in order to leave space for us to imagine what is not there. The art historian and painter Giorgio Vasari wrote of such imagery ‘hovering between the seen and the unseen’, which gets close to the heart of the matter. The landscape in the Mona Lisa is emergent seeing. It is a kind of dawn, like the dawn we saw at the beginning of this book.

Lisa del Giocondo’s famous smile is dawning, like the light is dawning, like a baby’s vision dawns. And although we know that this is a real woman, born on 15 June 1479, and although her clothes and hairstyle are of their time and place, the sfumato clouds her and her place in the world. The unseen that Vasari mentions is the intangible, the numinous. Lisa looks like we dreamt her, like she is in a dreamscape. More than three centuries after Leonardo, the English painter J.M.W. Turner would take his idea of the defocused landscape to an extreme by painting using his peripheral vision, in other words turning his head away from his subject so that it became entirely soft edged. In Turner’s Seascape with a Sailing Boat and a Ship, nothing is pin sharp. The sky, clouds, sea and vessels fuse into each other as if they are one amorphous visual entity.

Turner was using soft focus to show the visual occlusions of sea, weather and objects, but on the other side of the world, a century later, out-of-focus imagery that resembled his paintings was used to suggest something other than love, closeness, dream or tempest. Look at this similar image from the 1953 film Ugetsu Monogatari:

Here director Kenji Mizoguchi has the scene shot with a long lens, diffused light, a smoke machine, a diffusion filter and low contrast to coax us of out of our hard-edged, three-dimensional, everyday life into a floating world. The setting is Lake Biwa in the late 1500s. Two peasants, who live modest, decent lives, want more. Their wives try to convince them not to be too ambitious, but hubris takes over. One of them, the potter Genjurō, falls for an aristocrat, Lady Wakasa, who admires his work. She seduces him and asks him to marry her. In this famous image, he seems to carry her on his back.

Cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa’s focus is again shallow, the contrast is low. There are no blacks or whites, just shades of grey, as if their world is fogged, or floating. It is, in a sense, floating, because it is revealed that Lady Wakasa is a ghost. Miyagawa uses soft focus as a ghostly thing, as a way of depicting a haunted, parallel world.

Artists have continued to be interested in this parallel world. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the German artist Gerhard Richter regularly produced large, blurred images of faces and the sea that gave the sense of primal seeing. He said in an interview that he blurs ‘to make everything equal, everything equally important and equally unimportant’. He could be talking about the out-of-focus seeing of a newborn child in which most things, with the exception of faces, have equal weight. The very first impressions on the blank pages of a baby’s inner eye are mysterious, ghostly and imprecise about place and space. They are the foundations of our future seeing.

LOOKING OUT AT THE WORLD

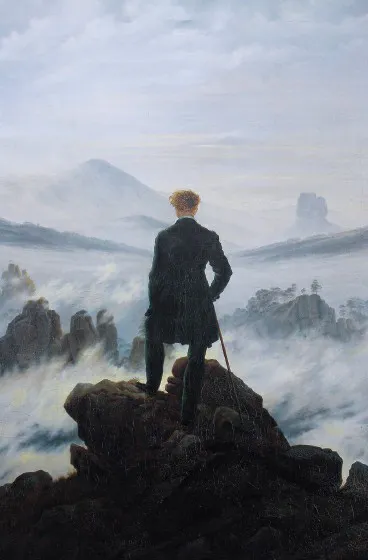

Let’s think of our African baby from 200,000 years ago again. Once she learns how to focus, what she next sees, before colour, is space. The blank spaces start to acquire dimensions. Having two eyes allows her to see and judge distance, what is close and what is far. Unlike a horse or rabbit, whose eyes are on the sides of their head and who therefore see to their left and right, humans eyes are frontal, and so our looking is substantially forward. We have a greater sense of where we are going than where we are. As we grow up, we develop an aesthetic of near and far, an emotion. This man, in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog of 1818, looks out into a landscape not unlike Lisa del Giocondo’s, but where she has her back to hers, he has his back to us.

We are looking with him not so much at a landscape as into a vast space. The space makes him feel small, overwhelmed by the size of the world. The effect is consoling; it takes him out of himself, what the anthropologist Joseph Campbell called ‘the rapture of self-loss’.

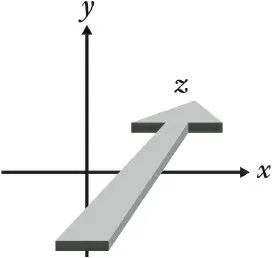

We do not only perceive space when we climb mountains, of course. We want a room with a view. A house or flat with such a view will sell for more than one without. As we will see later in our story, the drive to invent hot air balloons and tall buildings comes, in part, from the desire to see space. Images are no longer things that appear on the blank pages. They appear in them. In terms of geometry, where an x-axis is left–right and a y-axis is up–down, in–out is the z-axis – that line in space that links us with everything in front of us.

In southern Scotland, on raised moorland overlooking this view, the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay built six small stone walls which carry the words

LITTLE FIELDSLONG HORIZONS

LITTLE FIELDS LONGFOR HORIZONS

HORIZONS LONGFOR LITTLE FIELDS

LITTLE FIELDS LONGFOR HORIZONS

HORIZONS LONGFOR LITTLE FIELDS

The first line captures the smallness of the looker and the distance of the looked-at – the length of z. By moving the word ‘long’ in the second line, he doubles its meaning – far and wanted. We want the afar, that which stretches into the distance. The z-axis is implicated in desire; it is our sense of adventure, our wanderlust and the way that we visualise the future that lies ahead.

Reprinted by permission of the estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay

The story of z-ness, of the journey from in to out in the visua...

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Starting

- Part 2: Expanding

- Part 3: Overloading

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits

- Index