- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

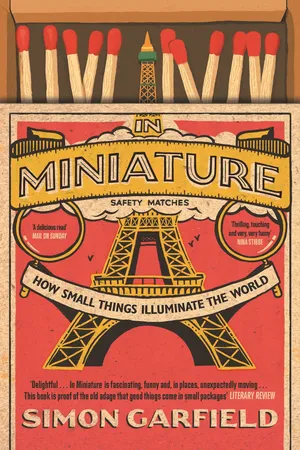

In Miniature is a delightful, entertaining and illuminating investigation into our peculiar fascination with making things small, and what small things tell us about the world at large.

Here you will find the secret histories of tiny Eiffel Towers, the truth about the flea circus, a doll's house made for a queen, eerie tableaux of crime scenes, miniature food, model villages and railways, and more. Simon Garfield brings together history, psychology, art and obsession, to explore what fuels the strong appeal of miniature objects among collectors, modellers and fans, and teaches us that there is greatness in the diminutive.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In Miniature by Simon Garfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The View from Above

Amid the many expressions of outrage and delight that accompanied the opening of the Eiffel Tower in the late spring of 1889, there was one response that took even its creators by surprise. Visitors were shocked to find that the tallest structure on earth had suddenly shrunk the world around it.

Anyone possessed of the immense courage necessary to climb the 363 steps to the first platform, and then 381 to the second, saw the world beneath anew. A cliché now, but then it was a revelation: people had become ants. This is what the birth of modernism looked like: an iron-clad sense of upward progress coupled with an omniscient sense of measured order. From above, Paris was both map and metaphor. Unless you had previously floated in a balloon, this was the first time the world appeared to scale: Haussmann’s boulevards became grids; the World’s Fair glittered like a bauble below, and its chaos was momentarily quelled. The thrill of the climb culminated in blissful serenity: the stench of horse manure and soot just evaporated. On a clear day the views stretched to Fontainebleau and Normandy, to the chalk of Dover and the inglorious Belgian battlefields of Waterloo, and, beyond that, to the clear pure future of everything.

Because all of this was new, it was also noteworthy. Those who went up the Eiffel Tower in the first few months kept a careful record of what they saw, for their way of seeing was as new as the tower itself. Reading their prose today, we may still perceive their wonder humming along the gantries. ‘He climbs slowly, with his right hand on the bannister,’ one reporter noted as he followed Gustave Eiffel up the stairs before the official opening (even the climbing was novel; the highest fixed view before had been the gallery at Notre Dame). ‘He swings his body from one hip to the other, using the momentum of the swing to negotiate each step.’ Even on the first platform (190 feet) ‘the city already appears immobile. The silhouettes of passers-by and fiacres are like little black spots of ink in the streets.’ The ascension continues until, at 900 feet, ‘Paris seems to be sinking into the night like some fabled city descending to the bottom of the sea amid a murmur of men and church bells.’ A few weeks later, once the tower had opened to the public, another observer described how ‘975 feet above the world people become pigmies . . . all that looked large had disappeared’. Eiffel himself described it as ‘soul-inspiring’ and hinted at the possibility of achieving a form of transcendence hitherto impossible – a higher, weightless plane. A reporter from Le Temps found he was overtaken by ‘an indescribable melancholy, a feeling of intellectual prostration . . .’ At 350 feet, ‘the earth is still a human spectacle; an ordinary scale of comparisons is still adequate to make sense of it. But at 1,000 feet I felt completely beyond the normal conditions of experience.’ The art critic Robert Hughes has observed that for the vast numbers who ascended the tower in its first few months the view ‘was as significant in 1889 as the sight of the Earth from the Moon would be 80 years later’.

The view from above continues to enthral: the thrill from the Shard or the Empire State is, at first sight, quite as enticing as the one that transfixed Parisians in 1889. Thirty years after the tower opened, the writer Violet Trefusis experienced the same thrill in an aeroplane. She called herself a ‘puny atom’, and she felt her old self die. She saw ‘a little map dotted with little towns, and a little sea’, and thought ‘what a wretched little place the world is! Humanity had been wiped out . . . It seemed to me that I had become suddenly and miraculously purged of all meanness, all smallness of spirit, all deceit.’ That peculiar combination of humility and awe – how insignificant we are among the clouds, but how significant to have advanced towards them – does not change with the seasons or the admission prices; they are adventures in scale, and in seeing our world afresh. Eiffel had given us 1,000 feet, the early plane 3,000; from all heights, the view beneath was miniature and the city beneath was ours.

Eiffel had designed his tower as a symbol of formal strength, a tour de force, the triumph of the machine astride a city hitherto fondly regarded for tender aesthetics. Its dizzying height was its virtue and its point. It was symbolism without purpose, and no wonder so many literary lights took against it. No one did so more vociferously than Guy de Maupassant, who classified it as ‘an ever-present and racking nightmare’. His loathing only intensified after it opened: the fable goes that, before he fled Paris to avoid the tower, he felt compelled to patronise one of the tower’s second-platform restaurants, for it was the only place in Paris he was in no danger of seeing the tower itself. Maupassant was joined in his indignation by fellow writer Léon Bloy, who tagged it a ‘truly tragic lamp post’.

But the public loved it, of course, and we still do. In the first week, almost 30,000 paid 40 centimes to climb to the first level, while 17,000 paid 20 centimes more to go to the second. Almost two million ventured at least part of the way during its starring role at the Exposition Universelle between May and October 1889, and many were delighted to encounter M. Eiffel himself, installed in his office halfway up. Here he welcomed Thomas Edison, Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, Grand Duke Vladimir of Russia, King George of Greece and the Prince of Wales.

But what use was the tower beyond scaling down the world beneath it? Its creator, troubled by the thought that others might see it as inconsequential and hubristic – a toy even – worked hard to establish its worth. (It’s fair to say that its investors had no such qualms – in its first five months the tower took admission fees of almost six million francs.) But Eiffel had aims beyond avarice, and inscribed the names of more than seventy French scientists around the first level to justify his monument, and perhaps equate his accomplishment with theirs. He stressed that his tower would have many meteorological and astronomical applications, and might even serve an important role in defence, should Paris ever come under attack.

But above all, and at its heart, the Eiffel Tower was a toy, and the lifts also made it a ride, and everyone could have a turn on it. It was a plaything for the newly wealthy industrialist, and it was a grand day out for tout le monde. The public needed none of the scientific justification sought by its engineer; they loved it merely for its wonder.

But something else began at the Eiffel Tower: the ability, at the end of the day, to take it home. The opening of the tower marked the birth of the mass-consumed souvenir and the dawn of the factory-made scale model. The Shah of Persia left with a tower-topped walking cane and two dozen iron miniatures, enough for the whole harem. Other visitors found trinkets at every turn, with kiosks on every floor. Predictably, Guy de Maupassant didn’t like this either: not only was the tower visible from every point in the city, ‘but it could be found everywhere, made of every kind of known material, exhibited in all windows . . .’ The Eiffel Tower not only shrunk the world, but it shrunk the world on your mantelpiece too. Henceforth, a symbol only truly became part of the landscape when it also became part of one’s luggage home.

The tower was available in pastry and chocolate. Handkerchiefs, tablecloths, napkin rings, candlesticks, inkstands, watch chains – if something could be made tall, triangular and pointy it was. The most dazzling was the Tour en diamants, 40,000 stones in all, on show at the Galerie Georges Petit in the tower’s shadow. But the tower was also available in less precious metals in every other shop, and almost 130 years later production has yet to slow. Gustave Eiffel believed that souvenir rights were his to trade, and he granted an exclusive image licence to the Printemps department store on Boulevard Haussmann. The agreement lasted but a few days, or just until every other Parisian shopkeeper brought a class action lawsuit arguing that such a magnificent day out in the sky should be celebrated and exploited by all.

The word ‘souvenir’ is, naturally, French. Its translation denotes its purpose: ‘to remember’ (an earlier version of the word first appears in Latin: subvenire – to bring to mind). A miniature souvenir does not diminish its worth, for its partiality supplies its force: it provokes a longing to remember and tell its story. The Eiffel Tower at sunset, drink in hand, just the two of you, we’ll always have Paris – that’s never a story that gets any smaller.

Of course, true miniaturists may not be content until they have made the souvenir themselves. Frequently in these pages we will encounter miniaturisation as an all-consuming hobby, and we will discover that our appetite to manipulate a reduced world is only partially sated by ownership; we also must satisfy our innate human need to create. A handmade miniature Eiffel Tower was always going to be a challenge, but the ultimate challenge would be to make it out of something that was both seemingly impossible and evidently stupid. So we should, in the first instance, admire both the application and the triumph of a New York dental student who, in 1925, built a model of the tower with 11,000 toothpicks. According to Popular Mechanics, which photographed the student in a long white coat ‘putting finishing touches’ to the model just a little taller than he was, the whole enterprise required tweezers, glue and approximately 300 hours. And there was a scientific justification for it: by building the model from toothpicks, the unnamed student confirmed the triangular structural rigidity of the genuine tower (not that this really needed proving after so many millions had ascended it).

In the 1950s, a 5-foot version was made in Buenos Aires, this time from international toothpicks gathered from all over the world: a global media appeal yielded an enthusiastic response from hundreds, and they mailed in their wooden splinters as if reacting to an emergency disaster appeal. After that it was only a matter of time before the enthusiast’s material of choice switched from toothpicks to matchsticks, and so it proved when a Detroit man named Howard Porter occupied his days by gluing together an Eiffel model at 1:250th scale using 1,080 small matches, 110 larger fireplace matches, and, for old times’ sake, 1,200 toothpicks. Like the model by the New York student, this also took around 300 hours to build, but both of them would be made to look like lightweights compared to the French watchmaker Georges Vitel and family, who spent several years and an estimated half a million matchsticks building the tower at 1:10th scale. When the French press celebrated it in 1961 (‘La Tour Eiffel – En Allumettes!’) it was almost big enough to climb. Better still, or worse still, the 70-kilo model was wired up to the mains. The electrics operated the internal lifts, and lit the lamps in the tower’s restaurants. Because Georges Vitel and his family didn’t live in a chateau, but in a quiet suburban house in Grigny, almost 30 kilometres south of Paris, the team had to build the model in two sections, top and bottom, both of which reached the ceiling of their living room. They had a television, but the tower blocked the view. Was this part of a life well spent, or was there a suggestion that the Vitels judged life so disappointing that all that remained for them to do was bolt the doors and get matchsticking?

Seventy kilos of matchsticks: the Vitel family applying the finishing touches in their living room.

A miniature, even a miniature that reaches the ceiling, is a souvenir in physical form, a commemoration of our own tiny imprint on the planet. We made this, we say; we bought this. We understand and appreciate this. Sometimes we control this. These are fundamental human desires, and they lie at the heart of our lives and at the heart of this book. But what happens when we believe that a miniature souvenir from this world may be carried forward to the next?

Safe passage to the underworld, and an afterlife of leisure: shabtis from the tomb of Seti I in the Louvre.

Mini-break, 3000 BCE: Egypt’s Coffins

On 16 October 1817, the great Italian Egyptologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni instructed his workers to start digging at the foot of a steep hill in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile. His diggers were dubious: why would there be anything at all in this waterlogged place? (It was more than a century before the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered nearby.) Towards the end of the following day, 18 feet down, Belzoni’s workers hit rock. The rock was the entrance to the tomb of King Seti I, the ruling pharaoh of Egypt for more than a decade before his death in 1279 BCE. The tomb was elaborate and well preserved, and within it lay evidence of how we once invested the miniature with profound responsibility.

Signor Belzoni, a high-collared dandy who was as much at home in the temples of high fashion as he was in crumbling mummy pits, loved astonishing audiences with his tomb-raiding adventures (in London, in earlier and more downtrodden days, he developed his showmanship as a strongman in a circus). He once wrote of a Theban discovery where his face made contact with decaying Egyptian mummies as he passed by, and where he ‘could not avoid being covered with bones, legs, arms and heads rolling from above.’ He described walking the deep chambers beneath the Valley of the Kings with equal drama, of encountering deep wells and hidden side rooms with hieroglyphics and paintings that looked as if they had been created yesterday (there were ten chambers off seven corridors). He tunnelled his way into great pillared halls and found staircases that led to chambers he named the Room of Beauties (paintings of women on the wall), the Bull’s Room (containing a mummified bull) and the Room of Mysteries (no one knows). He found wooden statues and papyrus rolls, and as he went further and deeper he came to the final burial chamber holding an ornately carved alabaster sarcophagus. ‘It is useless to proceed any further in the description of this heavenly place,’ he wrote, ‘as I can assure the reader he can form but a very faint idea of it from the trifling account my pen is able to give; should I be so fortunate, however, as to succeed in erecting an exact model of this tomb in Europe, the beholder will acknowledge the impossibility of doing it justice in a description.’

In 1821 Belzoni did manage to bring a few of his discoveries to London’s Piccadilly, and they attracted a large public. Alongside other treasures, Belzoni brought several intricately carved figurines made from blue-glazed pottery that had been buried with King Seti’s body. These were shabti dolls, between 7 and 9 inches tall, each with a symbolic role to play in the Egyptian vision of what happened after death. Each would relieve the travelling soul from performing manual work in the afterlife, the precise nature of the task revealed in the hands crossed against the shabti’s chest: a vase may release the bearer from serving or vineyard work, while a basket would rule out harvest or other reaping chores. While those buried around 2000 BCE might have been accompanied to the next world by only one or two shabtis, the wealthier souls of Egypt living in the later dynasties between 300 and 30 BCE would be buried with several hundred. For a while the tradition became 401: one worker for every day of the year, and a string of ‘overseers’ holding whips to keep the workers in line.

The shabti is far from the oldest miniature representation of the human form. This accolade belongs to Venus figurines, usually obese and naked, and just a few centimetres tall, that date back 40,000 years. Only about 200 of these plump carvings are known to exist, whereas there are tens of thousands of later shabtis (which are also known as ushabtis and shawabties, depending on place of origin). The shabtis were made from limestone, granite, alabaster, clay, wood, bronze and glass, but most commonly from the blue-green sand-based pottery known as faience.

Because of their ubiquity, shabtis may be seen performing all manner of funereal tasks in Egyptology departments throughout the world. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo holds more than 40,000. Some of the finest examples are to be found in institutions in north-west England, including museums in Rochdale, Stockport, Macclesfield and Warrington, many of the exhibits gathered from the private collections and the ‘cabinets of curiosities’ of industrialists and gentlemen archaeologists of the nineteenth century. The British Museum also has a great hoard, including the magnificently preserved figurine of King Seti I, one of the shabtis discovered by Giovanni Belzoni 200 years ago, resembling a miniature mummy with a striped royal headdress. The figure ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Simon Garfield

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: The Art of Seeing

- 1. The View from Above

- 2. Miniature Villages and Cities, Some Happier than Others

- 3. Portrait of a Marriage

- 4. The Miniature Book Society’s Exciting Annual Convention

- 5. The Domestic Ideal

- 6. The Biggest Model Railway in the World

- 7. The Future Was a Beautiful Place

- 8. The Perfect Hobby

- 9. Theatre of Dreams

- 10. Our Miniature Selves

- Epilogue: This Year’s Model

- Acknowledgements and Further Reading

- Picture Credits

- Index