![]()

1

May I But Safely Reach My Home

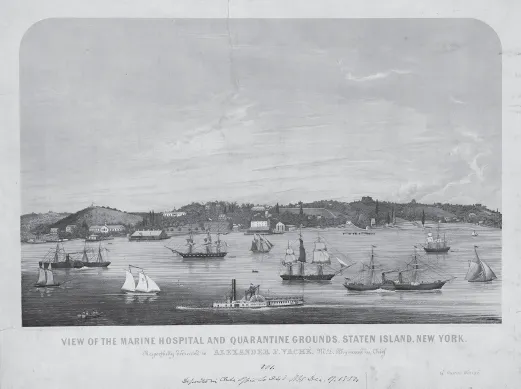

Tolbert Major woke at dawn on his last day in America. The sun cast a lavender and peach glow across the cotton curtain in his room at the Staten Island Quarantine Center. Tolbert sat up in his cot and stretched, and then—whispering—woke his sons, Thornton, ten, and Washington, nine. They crept silently across the large room, weaving between the beds of dozens of other sleeping men and boys. They descended the back stairs and headed across the yard to the outhouse. When they finished, Tolbert sent the boys back to wake their uncle and cousins, and he ambled down to the pier.

The brig Luna rocked gently at anchor in the bay. Her two masts, wrapped in tightly furled sails and jibs, soared into the pink-tinged sky, and rigging spider-webbed across the vessel. On deck, the crew prepared to set sail for Africa on the afternoon tide.

Tolbert waved to one of men, and then, feeling the need to stretch his legs, he strolled around the quarantine grounds. The walled compound included twenty white frame and brick buildings, wide expanses of grass, a long wooden pier, and a beautiful view. Signs such as “Smallpox House” exposed the center’s true purpose, however, and Tolbert did not venture close to the other buildings. None of the formerly enslaved or freeborn black people preparing to board the Luna were ill, but New York’s mayor had housed them in a vacant building at the quarantine grounds until everyone in their group had arrived.1

As Tolbert walked, memories tumbled through his mind: topping tobacco plants in a Kentucky field, the long trip from Hopkinsville to the Northeast, and the smell of the crowds and horses in New York City. He thought, too, of the long voyage ahead of them and the promise of a new life.

By the time Tolbert returned to the building where he had slept, the rest of the emigrants were up. He and his sons carried their gear down to the pier. He spotted his brother, his nephews, and his niece. Agnes Harlan, their former neighbor in Kentucky, her kids, and Tyloa Harlan were already at the pier.

Seventy other people waited with the Majors and Harlans to board the Luna. Tolbert saw the Haynes family—John, a free black man from Nicholasville, Kentucky; his wife, Mary; and their children. Rachel and Robert Buchner approached, trailed by their large family. He spotted the Donelsons, formerly enslaved people from a Tennessee plantation just across the state line from the Major farm. Some of them talked and laughed; a few wiped away tears; others stared silently at the water, their thoughts already at sea. They all breathed deeply of the tangy salt air and tried to remain calm.2

Tolbert knew that the colonization movement, launched twenty years earlier, was controversial. Some people—black and white—supported the movement and its goals; others stood in fierce opposition. Still, he was convinced that going to Africa was right for him and his family. He recalled a scripture from the book of Micah about sitting quietly under a vine and fig tree; maybe he could find that kind of peace.

He eyed the piles of belongings: clothing, shovels and hammers, pots and pans, a rolled quilt, a straw hat. He, his brother, and their children had more possessions than they had ever owned. Joseph Major, their former owner’s brother, had seen to it that each of them had two complete outfits of new clothes, plus the basic supplies they would need. Some of the white ladies from the New York Colonization Society had stitched up even more clothes for the emigrants. The men of the colonization society had collected spades, rakes, hoes, building materials, and crates of books for a library.3

G. W. McElroy, the colonization agent who had brought them from Kentucky to New York, had told Tolbert that folks in New York and Pennsylvania had donated four hundred volumes for the settlers. Tolbert knew how to read; he wasn’t fast, but maybe now that he wasn’t a slave he would have time to finish a whole book.

The previous day—July 4, 1836, America’s sixtieth birthday—had been glorious. That morning, Tolbert had watched the steamer Bolivar make its way across the bay from Manhattan. When it docked at the quarantine grounds, several well-dressed white ladies and gentlemen, including the managing board and executive committee of the New York Colonization Society, had disembarked. Everyone funneled into one of the large public buildings on the grounds.

At ten o’clock, a send-off ceremony started with a spirited rendition of an old hymn. Those gathered harmonized on the final verse.

Let cares, like a wild deluge come,

And storms of sorrow fall!

May I but safely reach my home,

My God, my heav’n, my all.4

The Methodist Episcopal minister offered an opening prayer and then introduced Dr. Alexander Proudfit of the New York Colonization Society.5

“The moment for which you have been anxiously longing has at length arrived,” Dr. Proudfit intoned. “You are now embarking for the land which must be dear to you, as it contains the sepulchers and venerated ashes of your forefathers.”6

Tolbert didn’t know what to think about that. Yes, his ancestors were born in Africa, but that was a long time ago. Master Ben Major had told them that Africans led lives very different from their own. What would it be like there?

“We will probably never see you again in the flesh,” Dr. Proudfit continued. “We will always rejoice to hear of your prosperity and joy, and be ready to sympathize with you in whatever afflictions you may be called to endure. Recollect at the same time, that your situation is highly and awfully responsible; the results of your future behavior are unspeakably interesting to us, to your colored brethren whom you leave behind, and to the unnumbered millions in Africa.”

Tolbert liked Dr. Proudfit. The minister had visited them on Staten Island several times and seemed genuinely interested in their welfare. Still, the man could go on. He exhorted them to work hard, obey the laws of the colony, avoid hard drink, and be strictly upright in all their dealings with the Africans.

“With these few instructions, beloved friends, we bid you an affectionate farewell. Be perfect, be of good comfort, be of one mind, live in peace. May the One whose voice the winds and waves obey protect you on the mighty deep. Amen.”

Two other white ministers then stepped up and prayed over the assemblage. Finally, Reverend Amos Herring, a former slave from Virginia, stood. He prayed for safe passage and God’s guidance in their new venture before leading the gathering in a closing hymn.7

The pomp and ceremony ended, and the building emptied quickly. Most of the white visitors trekked back down the sloping lawns to the pier, the ladies’ full skirts sweeping the grass. They boarded the Bolivar and, with cheery waves to those on shore, they steamed back home to Manhattan, their families, and afternoon plans.

The black people who had attended the ceremony—the Majors, Harlans, and others who were migrating to Liberia—stayed at the quarantine grounds. They spent the afternoon washing and packing clothes and other supplies. In the evening, they shared a meal. That night, fireworks splashed across the sky, and cannon and musket shots reverberated as New Yorkers celebrated Independence Day. Children, weary from the day’s excitement, crawled into the laps of nearby adults and fell asleep.

At mid-morning the next day, Captain Hallet stepped to the Luna’s rail and hollered, “Permission to board!” The brig’s crew made trip after trip in small boats, ferrying supplies, baggage, and passengers to the waiting ship. As Tolbert and the others stepped aboard, the adults gave their names, ages, occupations, and family information to a colonization society clerk. They stowed their belongings and the children scampered off to explore the ship.8

G. W. McElroy and Dr. Proudfit boarded the vessel, too. They chatted with passengers, offered last-minute advice, and checked to make sure all was well. Reverend Herring, the group’s de facto leader, boarded the Luna with his wife, Leonora, and their little girl, Mary. It wasn’t his first trip to Liberia. He had scouted the West African colony three years earlier.9

Reverend Herring and Dr. Proudfit cobbled together a makeshift altar on the brig’s quarterdeck, led some prayers and hymns, and preached a little more. Tolbert listened impatiently. He had other business to attend to. Finally, the ceremonies ended with a fervent “Amen!” Tolbert glanced across the deck and caught Tyloa’s eye. He wove through the crowd of passengers, trailed by his sons. They stepped over and around bundles until they reached her side. Tolbert smiled and took her hand.

They had talked about this the night before, under a dark sky dazzled by fireworks. Now the couple and Tolbert’s sons made their way back to the quarterdeck, where Tolbert and Tyloa stood before Dr. Proudfit. The minister, in a simple ceremony, joined the smiling pair in marriage. The other passengers let out a lusty cheer, and even the usually staid Mr. McElroy beamed.10

Tolbert and Austin Major, Agnes Harlan, and dozens of other immigrants bound for Liberia were housed at the Staten Island Quarantine Grounds until the entire group was gathered and ready to set sail. (Brown and Quinlin, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-00331)

Five o’clock neared, and with it the afternoon tide. Mr. McElroy, Dr. Proudfit, and a few others disembarked the Luna by descending a rope ladder and stepped into a smaller craft. They turned, waved to the vessel’s passengers, and shouted “Farewell” and “God bless you!”

G. W. McElroy, the colonization society agent, stepped out of the rowboat and back onto the pier at the quarantine grounds. He turned and watched the Luna’s crew weigh anchor. It was a new beginning for those on board, but an ending of sorts for him. He had labored for months to rescue these men, women, and children from slavery—many of them from his native state of Kentucky.

McElroy thought about all those years he had supported the abolitionist cause. He had become frustrated as years passed with no progress toward ending the wicked practice of slavery and had finally turned to the cause of colonization. It seemed the best compromise, though he would have preferred to see slavery end altogether. He had signed on as an agent for the New York Colonization Society, but before he could put his full support behind the cause, he had wanted to see the colony for himself.

As he watched the Luna’s crew, he remembered the day more than a year earlier when he had boarded a similar ship filled with people bound for Liberia. He had spent several months in the colony and concluded that colonization was a holy cause. Even a bout of malaria hadn’t dampened his enthusiasm. In a letter to the editor of the New York Commercial Advertiser, McElroy wrote, “My zeal for Africa is by no means cooled, nor ever will be, I trust, until my head is buried in the dust … for Africa, I hope to live, and labor, and pray.”11

When McElroy had returned to the United States, he headed to Kentucky to secure passengers for the society’s next departing ship. He spoke numerous times throughout the state and met with supporters, free black people, slave owners, and others interested in learning about colonization. He even published a notice in the Louisville newspaper announcing the next planned expedition.12

After months of hard work and planning, McElroy secured freedom and a chance to migrate for fifty-six enslaved people. Ben Major and George Harlan of Christian County, Kentucky, and several other Kentucky slave owners freed their people for colonization, as did the estates of Alexander Donelson (Andrew Jackson’s brother-in-law) and Peter Fisher of Tennessee.13

For enslaved people, being freed through a master’s will wasn’t a sure thing. The Fisher slaves had had to go to court to secure the freedom promised by their late owner. The Chancery Court of Carthage, Tennessee, ruled that, if freed, the Fisher slaves would not only have to leave the state, they would have to migrate to Liberia.14

Finally, in early summer, McElroy and his charges had set off from rural southwestern Kentucky and traveled up the Cumberland River to the Ohio River, then on to Pittsburgh. McElroy was still angry about the disaster that had occurred in Pittsburgh. While he met with members of the city’s clergy to solicit supplies, local abolitionists had lured away fourteen of his charges—four of the Fishers and ten of the Donelsons—and convinced them that they would be better off staying in America. A few of the Donelsons changed their minds and later rejoined the group bound for Liberia, but the others had vanished.

The colonization agent was indignant and dismayed. The absconders put him in a bad spot, but it was worse for the estates of the former slave owners. The administrators of Donelson’s estate had signed a $5,000 bond to ensure that, if freed, the slaves would go to Liberia. Administrators for Fisher’s e...