- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

HONORABLE MENTION RECIPIENT OF THE 2021 COMICS STUDIES SOCIETY EDITED BOOK PRIZE

Contributions by Joshua T. Anderson, Chad A. Barbour, Susan Bernardin, Mike Borkent, Jeremy M. Carnes, Philip Cass, Jordan Clapper, James J. Donahue, Dennin Ellis, Jessica Fontaine, Jonathan Ford, Lee Francis IV, Enrique García, Javier García Liendo, Brenna Clarke Gray, Brian Montes, Arij Ouweneel, Kevin Patrick, Candida Rifkind, Jessica Rutherford, and Jorge Santos

Cultural works by and about Indigenous identities, histories, and experiences circulate far and wide. However, not all films, animation, television shows, and comic books lead to a nuanced understanding of Indigenous realities.

Acclaimed comics scholar Frederick Luis Aldama shines light on how mainstream comics have clumsily distilled and reconstructed Indigenous identities and experiences. He and contributors emphasize how Indigenous comic artists are themselves clearing new visual-verbal narrative spaces for articulating more complex histories, cultures, experiences, and narratives of self.

To that end, Aldama brings together scholarship that explores both the representation and misrepresentation of Indigenous subjects and experiences as well as research that analyzes and highlights the extraordinary work of Indigenous comic artists. Among others, the book examines Daniel Parada's Zotz, Puerto Rican comics Turey el Taíno and La Borinqueña, and Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection.

This volume's wide-armed embrace of comics by and about Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Australasia is a first step to understanding how the histories of colonial and imperial domination connect the violent wounds that still haunt across continents. Aldama and contributors resound this message: Indigeneity in comics is an important, powerful force within our visual-verbal narrative arts writ large.

Contributions by Joshua T. Anderson, Chad A. Barbour, Susan Bernardin, Mike Borkent, Jeremy M. Carnes, Philip Cass, Jordan Clapper, James J. Donahue, Dennin Ellis, Jessica Fontaine, Jonathan Ford, Lee Francis IV, Enrique García, Javier García Liendo, Brenna Clarke Gray, Brian Montes, Arij Ouweneel, Kevin Patrick, Candida Rifkind, Jessica Rutherford, and Jorge Santos

Cultural works by and about Indigenous identities, histories, and experiences circulate far and wide. However, not all films, animation, television shows, and comic books lead to a nuanced understanding of Indigenous realities.

Acclaimed comics scholar Frederick Luis Aldama shines light on how mainstream comics have clumsily distilled and reconstructed Indigenous identities and experiences. He and contributors emphasize how Indigenous comic artists are themselves clearing new visual-verbal narrative spaces for articulating more complex histories, cultures, experiences, and narratives of self.

To that end, Aldama brings together scholarship that explores both the representation and misrepresentation of Indigenous subjects and experiences as well as research that analyzes and highlights the extraordinary work of Indigenous comic artists. Among others, the book examines Daniel Parada's Zotz, Puerto Rican comics Turey el Taíno and La Borinqueña, and Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection.

This volume's wide-armed embrace of comics by and about Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Australasia is a first step to understanding how the histories of colonial and imperial domination connect the violent wounds that still haunt across continents. Aldama and contributors resound this message: Indigeneity in comics is an important, powerful force within our visual-verbal narrative arts writ large.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Graphic Indigeneity by Frederick Luis Aldama in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Comics & Graphic Novels Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of MississippiYear

2020Print ISBN

9781496828026, 9781496828019eBook ISBN

9781496828033PART I

MAINSTREAMED INDIGENEITIES

“We the North”: Interrogating Indigenous Appropriation as Canadian Identity in Mainstream American Comics

Indigenous characters—as appropriated by primarily white mainstream comics artists—are often coded as markers of Canadian identity in mainstream American1 comics in a larger echo of Canada’s own corporate, institutional, and governmental practice. In many ways, American mainstream superhero comics (and the scholarship written about them) are merely repeating a cycle of convenient and ahistorical appropriation that has been central to the branding of Canada, especially to a global audience, for much of its history. For example, in their 2010 article “Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940–2004,” Jason Dittmer and Soren Larsen begin a valuable interrogation of the way Canadian identity is often imagined in appropriated Indigenous terms.2 While their work on the Canadian Whites-era of Canadian comics (sometimes called the Golden Age, through the Second World War) and Captain Canuck represents a substantial contribution to the study of comics in this country, which has not often focused on necessary questions of race and representation, their easy framing of Alpha Flight, wholly owned by Marvel Comics, as a “Canadian” comic—primarily because its creator John Byrne was Scottish-Canadian—offers grounds for further work. This chapter considers the implications of scholarly assumptions about so-called Canadian nationalist superheroes created and marketed by major American corporations and, more importantly, examines the appropriation of representations of Indigenous bodies to those ends.

The Canadian Nationalist Superhero and Superheroes Who Just Happen to Be Canadian

The concept of the nationalist superhero is one of the ideas most often discussed with regard to mainstream Canadian comics scholarship, and for good reason: until the 1970s, the most popular comics made in Canada seemed to be expressly nationalist. Ryan Edwardson, in his article “The Many Lives of Captain Canuck: Nationalism, Culture, and the Creation of a Canadian Comic Book Superhero,” notes that

Distinctively national comic books are vessels for transmitting national myths, symbols, ideologies, and values. They popularize and perpetuate key elements of the national identity and ingrain them into their readers—especially, given the primary readership, younger generations experiencing elements of that identity for the first time.

When the comics are superhero comics, then, the superhero becomes emblematic of the expectations and stereotypes of the nation; their goals as heroes and do-gooders are aligned with the goals of the nation-state. Jason Dittmer notes in “Captain Britain and the Narration of Nation” that Captain America, with his pursuit of “truth, justice, and the American Way,” “can be understood as a foundation for the nationalist superhero genre” (71). Think about the way Captain America is named for his nation-state and draped in its colors, symbols, and flag, and you have a visual representation of nationalist superheroes.

As Bart Beaty outlines in his article “The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero,” “the temptation to provide the Canadian superhero with a distinctly nationalist identity, generally at odds with American-themed superheroes, has been one of the dominant hallmarks of the Canadian superhero genre” (429). This is rooted in the origin of Canadian comics; the Canadian comic book industry only emerged as a direct result of WWII rationing, which prevented the sale of US paper goods in Canada. Canadian publishers took up this opportunity to fill the void left, with titles like Nelvana of the North and Johnny Canuck. To speak plainly, these comics were simply not very good, having been created by people with passion but very little training or history in the production of comics; when the war ended and comics were once again imported from the United States, very few Canadian readers remained loyal to their Canadian comics. By 1955, the industry had collapsed, and there were effectively no English-language comics produced from 1955 to 1970.

As you might imagine given the time period, these WWII comics, known widely as Canadian Whites because of the paper stock they were printed on, were expressly nationalist in tone and content. Some characters, like Nelvana of the Northern Lights, were tasked with protecting Canada at home. Others, like the desperately and unintentionally hilarious Johnny Canuck, exist to fight abroad. As Bart Beaty points out, though, in their inherent Canadianness these characters are barred from being too exciting; they could be “active in the war, but not so active as to accomplish much of significance” (430). They were, if there can ever be such a thing, middle-power superheroes. They were nationalist in that they signaled a direct connection to the interests of Canada as a nationstate and often represented that nation-state, whether at home or abroad.

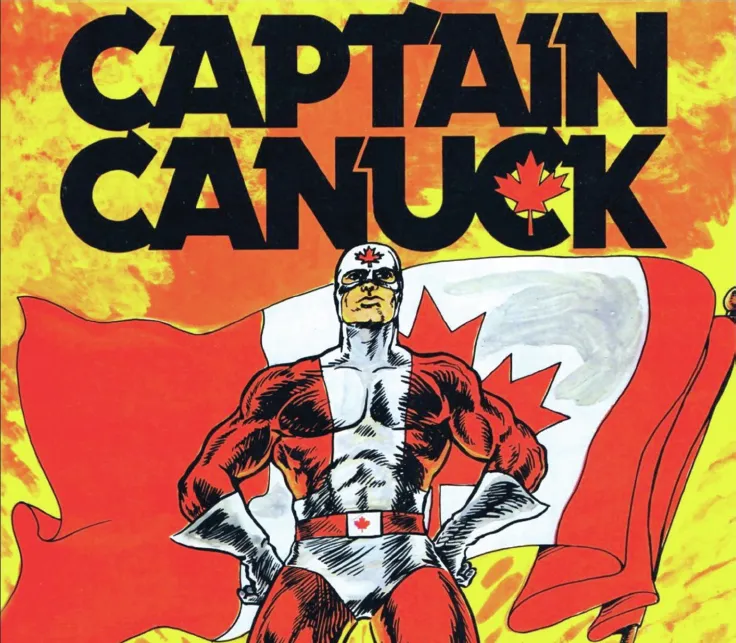

From 1955 to 1970, as noted, there were no Canadian comics of note published and thus the market was dominated by the mainstream American comics produced by big publishing houses like Atlas/Marvel and DC; this glut of American culture aligned with a Canadian centennial anxiety about the dominance of American culture in all aspects of Canadian life. Captain Canuck emerged as a response to this anxiety, and creator Richard Comely was expressly interested in engaging in nationalist sentiment in his comic. Edwardson notes that Captain Canuck primarily provides “Canadian comic book fans with a sense of national identity in a cultural arena where New York overwhelms New Brunswick, and one rarely sees a maple leaf” (199), particularly in the 1970s, when no other Canadian comics existed outside of the underground presses in Montreal and Toronto. Comely’s mission in creating Captain Canuck was expressly to fill what he saw as a cultural absence and establish an icon of identity. Comely also saw Captain Canuck as an opportunity to reinsert religion into a largely secular cultural space; while Captain Canuck didn’t explicitly share Comely’s own Mormon identity, he did pray before every mission and connected overtly his mission to protect Canada with his own godliness. (Later iterations of the character have dropped this religiosity.) It is worth noting that Captain Canuck was far more successful as an idea and as a trademark to be sold than he ever was as a comic book—his representation on a t-shirt has always had greater cultural cache than sales figures of comics featuring him might suggest—but new iterations of Captain Canuck recur every decade or so nonetheless.

As far as mainstream comics go, nationalist heroes were it for much of Canada’s publishing history in mainstream comics. So it’s natural that this area is a focal point for comics scholars interested in trends and expectations in Canadian comic books. But there is a trend in comics scholarship to assume that all superhero comics featuring Canadian characters are necessarily nationalist, and Alpha Flight is the series most commonly caught in this, as we see in Dittmer and Larsen’s article. This comes, I believe, from a comment Bart Beaty makes in his article where he notes that, compared to the mandated nationalism of Captain Canuck, Marvel’s Alpha Flight team is actually more broadly representative of Canada, including a linguistic and racial diversity rare in comics of that era (and today, unfortunately) and absent from the bland and blond superheroes of the nationalist comics movement in Canada. But Beaty specifically notes that Alpha Flight and other American-produced Canadian superheroes—characters like Wolverine and Deadpool in the Marvel Universe, for example—actually “undercut [ … ] Canadian nationalism” by relying “on some of the most obvious clichés about the nation” and the stories “prove [ … ] difficult to quantify as distinctly Canadian” (436–37). Further compounding this issue, Dittmer and Larsen also commit the error of reading too uncritically our nationalist comic historian John Bell,3 who tends to foreground creator nationality over corporate context in outlining the history of Alpha Flight. While it’s true that Alpha Flight creator John Byrne lived in Canada and was trained at least in part at the Alberta College of Art and Design, of his own nationality he writes:

Captain Canuck. From Captain Canuck #1 (1974): cover. Reprinted by Chapterhouse Archive, 2016.

I’ve been a citizen of three different countries. I was born in England, so I got that one the easy way. When I was 14, my parents became Canadian citizens, and I floated in with them. Then, in 1988, after having lived in this country the prerequisite number of years, I became an American citizen. (In full. I do not hold dual citizenship. I do not hyphenate myself.)4 (Byrne)

As much as there seems to be an inherently Canadian drive to claim all tangentially related cultural figures as our own, it is clear here that Byrne does not see himself as Canadian; his choice of the phrasing “floated in with them” to describe how he acquired his Canadian citizenship suggests a lack of agency in or commitment to that identity.

Alpha Flight is really only Canadian because it was convenient for them to be Canadian, and they emerged at a time when Marvel was trying to expand the geographic base of its subscribers and diversify (mildly!) its offerings. This was around the same time as the launch of, for example, Captain Britain in the UK. The team was introduced as a foil to the X-Men in 1979, and then quickly achieved their own series. Alpha Flight was a viable title as long as it was making money. The most successful comic to feature Canadians—the first issue earned creator John Byrne a record-breaking thirty thousand dollars in 1984—was not a nationalist comic; indeed, as Beaty points out, it “helped to marginalize Canadian concerns within the so-called Marvel universe” in a single title about characters who regularly lost to American superhero teams. (To understand just how expressly Alpha Flight was not intended to be a nationalist comic for advancing Canadian interests, one can read the lettercols or letters to the editor from the 1980s and 1990s, where Canadians who write in to complain about geographic or cultural inaccuracies are roundly mocked by the creative team.)

We the North: National Identity Via Indigenous Appropriation

The “We the North” phrase of my title comes from the marketing of Canada’s only (current) NBA basketball team, the Toronto Raptors, and indicates in a relatively minor way that the appropriation of northern and Indigenous identities stands in for discussion of Canadian identity. As we have seen from recent pop culture stories such as the DSquared2 clothing line D-Squaw, appropriation of Indigenous identity as a signifier of Canadianness, particularly for an international market, is an ongoing issue. DSquared2 is a fashion label owned by Italian-Canadian twins Dean and Dan Caten that sells a high-end conception of stereotypical Canadian identity to European clients5 (one season featured a showroom draped in furs and flannel) with Canadianness obviously heavily coded through Indigenous imagery. The DSquaw line, launched early in 2015, was described by the Catens as, “The enchantment of Canadian Indian tribes. The confident attitude of the British aristocracy. In a captivating play on contrasts: an ode to America’s Native tribes meets the noble spirit of Old Europe” (“Canadian Fashion Label Dsquared2 under Fire for #Dsquaw Collection”). This combination, including deeply troubling items like a wedding dress, seem to celebrate colonization and evince a celebratory tone; the sense is that this relationship and the coming together of these “contrasts” results not in rape and genocide, but beauty and fashion.6 Groups like ReMatriate, a collective of “female fashion designers, singers, models, architects, artists, and advocates,” are working to reframe these kinds of appropriations in explicit colonial terms, noting that for settler populations to treat cultural practices they once outlawed now as part of the public domain is deeply offensive (“ReMatriate Wants to Take Back ‘Visual Identity’ of First Nations”). Further, to call these images, ideas, and artifacts somehow inherently “Canadian” after the Canadian nation-state used generations of cultural violence to attempt to eradicate them is truly grotesque. But for generations, Canada has sought to have it both ways: to quash Indigenous nations at home while projecting Indigenous iconography as representative of Canada abroad. Take, for example, the branding for the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver: the use of Haida and other Indigenous nations’ imagery (including the central logo, the Inuksuk, which is a symbol and practice of the Inuit and shares no territoriality with the site of the Olympics) belied the mass displacement of, for example, homeless youth—who are disproportionately Indigenous—from Vancouver for the Games. And even earlier attempts to brand Canada globally, like the Centennial and Expo 67 use of Oopik, an Inuit handicraft,7 suggests that this has long been a corporate/government strategy: look to the Arctic North specifically and Indigeneity more generally to represent “authentic” Canada for a global audience.

This desire to appropriate without thought to obligation or responsibility is nothing new. In his Souvenir of Canada project, Douglas Coupland, Canadian artist and writer, tells the story of being asked to create a piece of Indigenous-inspired work for one of his first design jobs in 1984. Tasked with creating flash cards—one of which was to display Indigenous art—for a stadium in Vancouver, he writes:

I was told to mock one up quickly for a meeting, so I invented a fake thunderbird-motif flash sequence. The meeting went well, and a week later I was asked to prepare a flash card sequence using genuine First Nations imagery. So I began to do research and generate designs [ … ] with none of them looking quite right to the committee. [ … ] It was finally decided to go with the original fake thunderbird sequence because it looked the most “Indian-y.” (Coupland 95)

This idea of the inauthentic being read as more real than the authentic by ignorant settlers is, Coupland contends, the end result of misunderstanding and mistrust stoked by the government. It also underscores the ways in which Indigenous iconography is appropriated for non-Indigenous use by Canadian corporations and communities. The practice is coming into increasing scrutiny now, but countless organizations over the years have chosen, as Coupland’s employers here did, to create for themselves an Indigenous iconography without following community practices and protocols, and often without involving Indigenous people at all.

We must also be mindful of how Canada is often explicitly sold abroad as a nation without colonial h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Nourishing Minds and Bodies with Indigenous Comics: A Foreword

- Graphic Indigeneity: Terra America and Terra Australasia

- Part I: Mainstreamed Indigeneities

- Part II: Decolonial Imaginaries Terra South

- Part III: Decolonial Imaginaries Terra North

- Afterlives: A Coda

- List of Contributors