- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

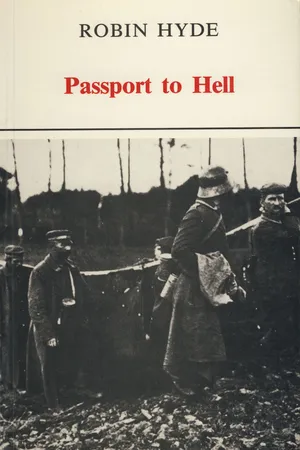

Passport to Hell

About this book

Passport to Hell is the story of James Douglas Stark—"Starkie"—and his war. Journalist and novelist Robin Hyde came across Starkie while reporting in Mt Eden Gaol in the 1930s and immediately knew she had to write his "queer true terrible story." Born in Southland and finding himself in early trouble with the law, the young Starkie tricked his way into a draft in 1914 by means of a subterfuge involving whisky and tea. He had a subsequent checkered career in Egypt, Gallipoli, Armentières, the Somme, and Ypres. Hyde portrays a man carousing in the brothels of Cairo and the estaminets of Flanders; looting a dead man's money-belt and filching beer from the Tommies; attempting to shoot a sergeant through a lavatory door in a haze of absinthe, yet carrying his wounded captain back across No Man's Land; a man recommended for the V.C. and honored for his bravery—but also subject to nine court martials. It is a portrait of a singular individual who has also been described as the quintessential New Zealand soldier.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Making of an Outlaw

WHEN the third Stark baby was born, they didn’t have to travel far to wet its head; the father, Wylde Stark, having by that time come into possession of the old Governor Grey Hotel, which stands white and square in the dusty plainlands of Avenal, near Invercargill town in the far south of New Zealand. The baby, a boy, arrived with no small inconvenience to its mother and some to itself at the hour of 1.30 in the morning. Down in the parlour, Wylde Stark’s guests and sympathizers had kept themselves awake to celebrate the event, a feat which called for a fair amount of refreshment. Technically, Invercargill may be a dry district; but there never yet was a time there when a man was ashamed by lack of good liquor for his friends. If the liquor consumed had really been bestowed on the baby’s head instead of on their own capacious gullets, James Douglas Stark would have started life with a head like a little seal’s. However, contrary to the practice of the new-born, he fell asleep almost immediately and took no interest whatever in the celebrations, which concluded only when dawn put a white finger of light to her lips and her stealthy winds said, ‘Sssh!’ very reproachfully to the company.

Though the same could not have been said of every man among his guests, Wylde Stark at five in the morning still looked as straight as a gun. He stalked upstairs, never touching the oak banisters with their carved Tudor roses, waved the sleepy-eyed nurse out of the way, and entered his wife’s bedroom. A gas-jet still spluttered blue and sulphur-yellow above the bed, for the baby had chosen July’s black midwinter for its arrival. His wife was awake, lying with her black hair and her paleness like sea-wrack against the crumpled pillows, her dark eyes watching him sombrely. He bent over the wicker cot where his second son had been bestowed, and inspected him without any show of sentiment. The baby slept on, unwhimpering. The tall man straightened himself.

A faint voice came from the pillows.

‘What is he like?’

‘Black as the ace of spades,’ said Wylde Stark briefly; and as though that should satisfy both his own curiosity and his wife’s, without another word he left the room.

Wylde Stark’s description of his third child was only correct among those who divide humanity into white men, yellow men, black men. The only things black in the composition of the small James Douglas—leaving out his later dislike of the police—were his perfectly straight hair and wide, sparkling eyes. For the rest he was a very seemly bronze colour—and this was far from being a prodigy or portent, since Wylde Stark, who fathered him, was a Delaware Indian from the regions of the Great Bear Lake. How a Delaware Indian came by the name of Wylde Stark is another matter, but the affair sounds as though possibly a Kentucky Colonel had at one time or another been following the grand old Kentucky custom of playing fast and loose among the Delawares.

Another fact which remains obscure is Wylde Stark’s reason for leaving the Great Bear Lake. All that is clear is that he arrived in Australia by cattle-boat, aged somewhere about thirty, and made straight as a homing-pigeon for the gold-fields. Here he enjoyed some considerable measure of success, both financial and personal. The latter rested mainly on his shooting of Higgins the outlaw, who made an ill-advised attempt to relieve the diggers of their dust. Wylde Stark’s bullet bored through his stomach, and there was no more Higgins the outlaw, but only an occasion for celebration—which, although it not merely wetted but flooded the whistles of his admirers, never made the stern Red-Indian face look any the less like carved mahogany.

When Wylde Stark came to New Zealand—not, this time, by cattle-boat—he had money and prestige. He settled down in the Governor Grey Hotel, and ruled his customers with a rod of iron, while the private comforts of his establishment rested in the slender hands of his wife—a tall girl born in Madrid, and of Spanish blood. How she came to marry her husband is not to be explained. But their life in Invercargill was a queer compromise between traditions. There was no Spanish background in her children’s early days except the occasional plaintive and broken spinning-thread of a song in the language that they never understood. New Zealand society having no gift of tongues, the Starks settled on English and stuck to it.

Wylde Stark was a dignified, almost an austere, figure, and physically superb. He stood six feet four-and-a-half inches high, and his wife was only six inches below him in stature—nothing at all below him in dignity. Whether their two racial prides ever fretted each other, their children had no inkling. They made common cause together in a society which could understand them very little. The colour line was much less rigid in New Zealand than it would have been in any other British dominion, but Wylde Stark was not to be satisfied with the good-humoured tolerance bestowed by the white New Zealander on his Maori brother. The Maori population in the South Island was scanty, and largely made up of slave tribes. The Maori who drifted into South Island towns smiled and lounged in the easy background of life. Wylde Stark, his straight-backed, pale-faced wife at his elbow, stalked through the psychological fences like some mahogany Moses.

Had James Douglas Stark at the age of one hour been able to appreciate the world at large, he must have admitted that his audience was worth notice. First, his enormously tall father, whose thin copper face was rendered amazing by its growth of white whiskers. Then, as the lovely moon-stone blue of dawn deepened and faded outside the windows of the Governor Grey Hotel, and the birds, awakening, showered down their many-coloured raindrop voices from the pines, two very singular figures crept into the room and stood over him like fairies at a christening. His brother, George, at the age of nine, was perhaps not very fairylike. He showed signs already of becoming the prodigy in height that a few years would make him. Trouser-legs, cuffs, collars, suffered wretched fates on an anatomy which grew and grew. George Stark’s complexion was considerably lighter than the new baby’s, but his thin lips and chiselled features were his father’s.

The second figure really was a fairy … a cousin to Rima herself, escaped from Green Mansions and tiptoeing here with her pointed, bronze-tinted face, her great eyes, her hair falling softly in ringlets upon narrow shoulders. Rose Stark won out of the grudging hands of destiny that loveliness which, when sometimes we see it in its lazy, unconscious moments, seems to us incredible. She was four years old and a sprite, neither Spaniard nor Indian, but a fusing of those two strange metals. Of the two hanging over the baby’s cot, Rose had the lively and laughing disposition; her brother, George, was a sober gentleman who even then resolved, from his superior height and age, to take the youngster in hand.

An astrologer might tell clearly how the stars stood at 1.30 a.m. on July 4th, 1898. But this much is certain. Mars the ruby-coloured, must have been pointing his brilliant stave straight down the chimney of that room where Anita Stark lay, her hair sombre against the white pillows. And what a Mars! … Sometimes with the face of a giant, sometimes a large and yet inordinately active policeman, sometimes a grinning sergeant, once a slim English officer with a slimmer yet wicked cane. The shapes of war, one after another, formed and dissolved round the sleeping child’s head. From under the pines, Wylde Stark’s Indian game-cocks crew their insolent and brassy challenge. The morning arrived pale and repentant. But the thing was done.

. . .

There were two moments in his life—one of sheer delight, one tinged with fear and a curious satisfaction. The delightful moment arrived when his father daily commanded him to let the horses out of the stable for their morning drink at the dam. The mornings, hazy over wide yellow fields, broken only by silhouetted pines and a blue circle of the inevitable New Zealand hills far away, smelt sharply of frosty soil; little puddles in the stable-yard frozen over with ice that tasted cold and slippery like glass; horse-dung trodden into the mire and yet gentled with the smell of warm straw. He let the big working horses out first, their breath wreathing blue as tobacco-smoke around their snorting velvet nostrils. Then he attended to the racehorses, of whom he particularly worshipped Avenal Lady. She was a chestnut girl, and his first love. He took the greatest pains in sleeking her beautiful long body, with the haughty arches of her ribs and the taper of her legs into satiny white stockings. The chestnut mare, recognizing perhaps a colour as temperamental as her own, blew frosty breath into the little boy’s face and beamed on him with her arch amber eye.

Avenal Lady’s lines of speed and grace were all the beauty the little boy could understand. He knew a good deal about races already, his father being known as one of the lucky owners of the Canterbury Plains, and the use to which her taut muscles in their wary satin sheath could be put was perfectly plain to his five years. But there was something more about her when she stood poised, reared up like a plume of fire, like a sheaf of tawny grain. She was triumphant in her beauty, and that was what the little boy very badly wanted to be himself.

He wasn’t supposed to be present at the cock-fighting, but the very thought of it made a salt taste like blood come on his tongue, and his small body could wriggle between the legs of the Invercargill men—some of them the toughest old sports in town. Cock-fighting, which was of course illegal, was not to be had outside the stable-yards of the Governor Grey Hotel. Wylde Stark had imported the Indian game-cocks, and a wizened little silversmith went to great trouble manufacturing and engraving their inch-long spurs of chased silver. Nothing was too good for the Stark gamecocks, and they flaunted their magnificence, strutting three feet high, great arrogant fowls, their plumage ruby and black, their feathered trousers sprayed out, absurdly like cowboy pants, around those deadly striking feet. The cock-fights were duels, usually to the death; and the little boy never found anything but excitement and joy in them until one day a cock with its eye torn out refused to die, but flapped round and round the ring, helpless among the legs of the black-trousered, red-faced males. Then he ran away.*

It should be possible for the son of a Delaware Indian to live from day to day, stolidly forgetting all except the needs and resources of the instincts. Did it come from Madrid, the shadowy faculty of being able to see again, to remember with a sometimes terrible distinctness, the strange things and the cruel ones just as they happened?

. . .

His father’s face was set like a rock. He said: ‘You’re going to put them on, don’t worry.’ And James Douglas Stark—his name now contracted to the popular version, Doug—squirmed again, but didn’t weep. Neither tears nor argument was the faintest use against his father. The rebel had two choices, to be trodden underfoot or to give battle. From the time when he could walk he had preferred to give battle.

Then a rope flicked out like a black snake and pulled him shrieking away from the fence to which he clung. His feet slithered, the rope scorching his waist; and yelling defiance, he was hauled to his father’s feet. His brother George was then commanded to sit on his head; and the world was thus darkened while Wylde Stark put on the feet of his lassoed son his first pair of boots. When it was finished, the boy felt that the last humiliation had befallen his brown toes. He scowled, looking like an overgrown Oliver Twist, was cuffed on the head and ordered off.

On the way to school he met George Bennett, and sold his new boots for twelve marbles. They were expensive boots—but, on the other hand, George Bennett’s marbles were worth talking about, being composed in equal parts of alley tors and glimmers. He was thrashed when he went home; but as he explained only that he had thrown the boots away—nothing about the trade with George Bennett—he retained possession of the marbles, and the beautiful little sparkly lights in the hearts of the glimmers when he held them up one by one to the gas-jet atoned for all else.

. . .

His father said: ‘You’ll stay at school all right.’

Starkie looked at him, with eyes whose limpid darkness prickled suddenly with glints of battle. For a schoolboy, those eyes could look amazingly innocent. It was hard, thought his first masters, that Starkie could play truant with all the perverse ingenuity of a dusky lamb among Bo-Peep’s sheep, and then turn up with the eyes and smile of a bronze cherub. Reason, kindness, sterner methods, all fell flat. So far as could be discovered, Starkie’s urge was not so much resentment against school, as a series of angel visions that slid gently into his mind at the wrong moment. He started off with the best intentions, plodding along the dusty Invercargill roads. Half-way, his genius revealed to him Starkie bird-nesting in the park…. Starkie with boots off and toes deliciously muddy, hauling up a whopper of an eel, an eel that all men would admire…. Starkie just wandering, on a road bent up like a teaspoon in the queer, flat-lidded saucer of the plains. Normal enough for little boys, in their classrooms, to shoot up their paws, with a hoarse, ‘Please, teacher, may I leave the room?’ Not so normal for them to vanish, and be discovered in God’s good time, trudging patiently towards the skyline. Starkie’s first school fought a losing battle with the great outdoors, and Wylde Stark, after a year, removed him to another.

Invercargill was not badly supplied with schools. The first establishment having failed, there remained the Waikiwi School, the Park School, and the Marist Brothers’ School—to say nothing of more expensive establishments beyond the reach of a Wylde Stark.

To each of these in succession James Douglas Stark was either led or driven. He never lasted longer than six months. There was no manner of real frightfulness about his escapades. He was simply schoolboy—large, intractable, cheerful, and unimpressionable schoolboy. Indeed, none of his schoolmasters appears to have made any real effort to impress him. One of the Victorian poets has a heart-murmur to the effect that the law of force being dead, the law of love shall prevail. This poem had not as yet travelled to Invercargill. The youngest Stark’s reputation as an outlaw preceded him, and masters rolled up their sleeves in readiness. Occasionally they had a really sound excuse, as when with a length of rubber and a pen he devised a new sort of harpoon, and—the lord of the Waikiwi School having his back turned to the class while working out a useful little problem on the blackboard—let fly with this horrible weapon, penetrating the fleshy part of the schoolmaster’s thigh.

At the Marist Brothers’ establishment, however, the schoolmaster—an arrogant Irishman—was a deal too quick for his notorious new pupil. James Douglas Stark arrived in company with the McCarthy twins, Chris and Pete. That Chris was making hideous faces when the roll-call was uttered in deep and solemn tones was some excuse for a brown face crumpling up in a smile at the wrong time. The arrogant Irishman was at his desk in a moment. A thin but nippy little cane slashed him thrice across the knuckles. ‘Now, my boy, don’t laugh at the wrong time,’ advised the arrogant Irishman.

As far as the Marist School was concerned, James Douglas Stark never smiled again. Five minutes later he begged permission to leave the class-room in order to attend to the demands of nature. Seven minutes, and he was legging it down the road in the direction of Thompson’s Bush. Thereafter thrashings, bullying, and cajoling were all one to him. He could be dragged to the Marist fountain, but never again led to drink. Between him and the Irish nation arose an enmity not easily mended. Ten years later, when thoroughly incapacitated for war service, he applied to a then very affable British General for leave in Ireland. He was informed that he could have any other part of the British Empire he liked, but to Ireland he might not go.

The affair with the Marist teacher was the end of his schooldays. In Wylde Stark’s desk accumulated a stack of neat but ineffectual summonses from the Truant Officer’s legal-minded friends. Had James Douglas been born into their own family circles they would have realized the impotence of laws in coping with some important human problems. Yet out of school hours there was never anything that one could actively dislike in the long-legged, dark-eyed, eternally smiling youth, whose whistle was the most elaborate and debonair in the whole of Invercargill. Only of one person was he afraid—his elder and much larger brother, George. Wylde Stark, in thrashing his son, was restrained by an affection which seems strange in a Delaware Indian. George Stark, when thrashing his younger brother, went stolidly ahead and thought of nothing but the subject in hand. But George, though formidable, could be dodged. If bread and circuses were the ruin of old Rome, eels and circu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Author’s Note

- Introduction to Starkie

- 1 Making of an Outlaw

- 2 Good-bye Summer

- 3 Ring and Dummy

- 4 Cup for Youth

- 5 The Khaki Place

- 6 Conjurer and Pigeon

- 7 Dawn’s Angel

- 8 Bluecoat

- 9 Court Martial

- 10 The Noah’s Ark Country

- 11 Suicide Club

- 12 Brothers

- 13 Passport to Hell

- 14 Le Havre

- 15 Runaway’s Odyssey

- 16 Rum for His Corpse

- 17 Sunshine

- 18 London and Laurels

- 19 Last Reveille

- Notes

- Robin Hyde’s Published Volumes

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Passport to Hell by Robyn Hyde in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.