- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict

About this book

First published in 1986, James Belich's groundbreaking book and the television series based upon it transformed New Zealanders' understanding of New Zealand's great "civil war": struggles between Maori and Pakeha in the 19th century. Revealing the enormous tactical and military skill of Maori, and the inability of the Victorian interpretation of racial conflict to acknowledge those qualities, Belich's account of the New Zealand Wars offered a very different picture from the one previously given in historical works. This bestselling classic of New Zealand history and Belich's larger argument about the impact of historical interpretation resonates today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict by James Belich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Australian & Oceanian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The Northern War

1

A Limited War

THE FIRST MAJOR CONFLICT BETWEEN THE BRITISH AND THE Maoris was the Northern War, fought in the area around the Bay of Islands between March 1845 and January 1846. The British were opposed by a section of the Ngapuhi tribe under the chiefs Hone Heke and Kawiti. Heke was the most prominent of the anti-government chiefs, and his name is customarily used as shorthand for the whole political leadership. In military terms, however, Kawiti was equally important. These chiefs fought not only the British, but also another section of Ngapuhi. The leaders of this group included Mohi Tawhai, Patuone, and Makoare Te Taonui, but Tamati Waka Nene was the most notable.

The orthodox view of the Northern War, a view common to virtually all twentieth-century works, is that the first stages were grossly mishandled by Governor Robert FitzRoy and his military commanders. The situation was then saved by the arrival of a new Governor, George Grey, who brought the war to a triumphant conclusion and secured a permanent peace through generous treatment of the defeated rebels. This interpretation will be questioned here. It will be argued that the war resulted in defeat for the British, and limited victory for Heke and Kawiti. The argument that Maori successes arose, not from British blunders, but from radical adaptation of the Maori military system is an integral part of this re-assessment.

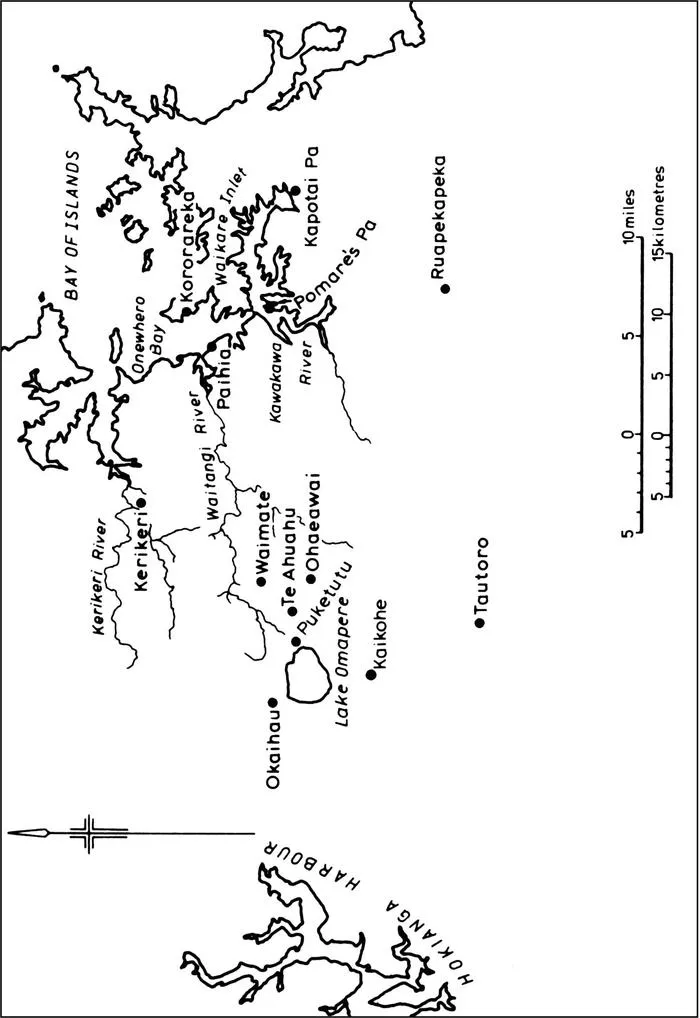

Though two battles—Kororareka and Te Ahuahu—fell outside it, the basic pattern of military operations in the Northern War was a series of British forays into the hilly and bush-clad interior. The three major expeditions (3–12 May 1845, 16 June-15 July 1845, and 7 December 1845–16 January 1846) were so distinct from each other as to be miniature campaigns in themselves. The first expedition was planned in late January 1845, to punish Heke for his defying the Government by cutting down the Union Jack at the important British settlement of Kororareka. At this stage, the British may have been content to teach Heke a lesson.1 But the expedition was not mounted until after Heke and Kawiti had captured Kororareka on 11 March 1845, and from this point the British objective became unequivocal and deadly. Each expedition was intended to kill or capture Heke or Kawiti and to destroy their forces.2 The objectives of both the resisting and the collaborating Ngapuhi factions, however, are less simple and they require closer examination.

I RESISTANCE AND COLLABORATION

SOME UNDERSTANDING OF THE DEEPER CAUSES OF CONFLICT IS important to the military analysis of the Northern War. If Heke was aiming to expel the British from the North and to turn back the clock to pre-annexation days, as is often implied, then he clearly failed. If his objective was less comprehensive, then the question remains open. The problem of war aims is complicated by the possibility that the Northern War was a three-sided conflict—that Waka had different objectives from his allies the British.

The differences between Ngapuhi resisters and collaborators were less remarkable than their common ground. Both groups adhered to the two great Maori principles of early race relations mentioned in the Introduction: a determination to uphold chiefly authority against arbitrary British interference, and a desire for interaction with Europeans. The division arose, perhaps, when measures in support of the former principle seemed to militate against the latter—when the defence of one aspect of the status quo threatened another. Thus the cleavage between resistance and collaboration was narrow; a matter of perception and emphasis, rather than fundamental attitudes.

The early British governors were aware that any attempt suddenly to impose substantive sovereignty was beyond their resources. But they did expect to impose ordinances, apply some laws, and take certain actions which concerned Maoris, without necessarily consulting the chiefs. Some measures which affected the Bay of Islands were the imposition of customs dues, restrictions on the felling of certain types of timber, and the removal of the capital from Kororareka to Auckland.3 All this diverted settlers from the North and reduced economic activity, and it coincided with a downturn in demand for New Zealand products in Australian markets. Government interference, in itself objectionable, was also acting against the second Maori imperative—an adequate level of interaction with Europeans. By reacting to this, Ngapuhi resisters were pushing for more European contact, not less.

Other government measures affecting the Bay of Islands included the execution of the minor Ngapuhi chief Maketu in 1842, for murder. The application of British law was only possible because it happened to coincide with Maori law, but it still created some resentment.4 When Robert FitzRoy, a conscientious man of some ability and more moral courage, became Governor in December 1843, he investigated land sales and applied the Crown’s pre-emptive right to the purchase of Maori land. His police magistrate at Kororareka, Thomas Beckham, did his best to apply British law in the town at least with the few constables available to him. The local settlers were naturally more reluctant to submit to chiefly arbitration and to Maori law. For Ngapuhi, this compounded the pre-existing problem of applying traditional law to the new range of disputes resulting from informal European settlement and contact, and of upholding chiefly authority in the face of this and other pressures.5

Bay of Islands, illustrating the Northern War (Chapters 1–3)

Hone Heke simply shared in the common recognition of the problem of government interference, but he was an exponent of vigorous solutions to it. One of these solutions, basically a peaceful policy, was the energetic application of Maori law and Maori local authority. Though they were hostile to his efforts, European observers could not fail to note them. One wrote that Heke ‘had constituted himself a Court of Inquisition: wherever he could hear of an offence, he would come down upon the offender with a taua [war party], on the plea of administering justice’.6 Comments like these have given Heke a reputation as a ‘congenital busybody’,7 but his activities are open to a more favourable interpretation.

His judgement was not unfair and his approach was not biased against Europeans under his control. The term ‘my pakeha’ implied responsibility as well as authority. In October 1844 he took one of his Pakehas to task for using timber from tapu (sacred) ground, but added that his lieutenant ‘will arrange for you to get the necessary trees on unconsecrated ground’. In general, his letter to this settler was intended: ‘to search out wrongs in every portion of the country … interpret these words to the Europeans, also to the Maoris … if you the Europeans, will do [your] part, I will do mine and make amends for any wrong acts of the Maori people’.8 Balanced as they were, Heke’s efforts were not appreciated by the settlers, who believed that substantive sovereignty now rested with their race. Maori law continued to be contravened in a variety of incidents, and the settlers became increasingly reluctant to part with the customary compensation for their misdemeanours.9

It seemed to Heke—and to most other northern chiefs—that the bulk of their problems and prospective problems arose from government attempts to interfere in their sphere of activity. In mid-1844, Heke decided to resist the incursions closer to their source, rather than to continue to rely on ad hoc efforts to cope with their effects. The problem with direct measures, however, was that they could easily militate against the second of the Maori imperatives. Heke, like most other chiefs, wished to preserve the valuable Maori-European economic relationship. When war broke out, Heke’s solution to this problem was to attempt to walk the fine line between conflict with the government and conflict with the Europeans as a whole. As he himself put it: ‘To the soldiers only, who are enemies to our power, to our authority over the land, also to our authority over our people, let our hearts be dark.’10

It is generally accepted that throughout the war he made every effort to avoid harming the settlers of his area and their property. Though some settlers chose to flee, others resided behind the lines in perfect safety. It is sometimes suggested that Kawiti had a different attitude, but in fact he too sought to protect the settlers and to prevent the looting of anything other than abandoned property. ‘Heki and the other chiefs declared it was never their intention to disturb the settlers, but on the contrary to protect them.’11 Missionaries observed that the occupation of their settlements by the anti-government forces did far less damage than the occupation by the troops.12 Other than those fighting as volunteers beside the soldiers, no civilians were int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART ONE : The Northern War

- PART TWO : The Taranaki War

- PART THREE : The Waikato War

- PART FOUR : Titokowaru and Te Kooti

- PART FIVE : Conclusions

- Glossary of Maori Terms

- References

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Copyright