- 592 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

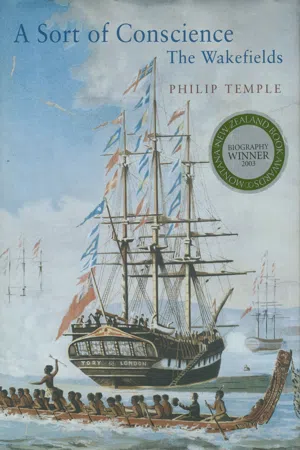

This in-depth portrait of the Wakefield family, who played such a major role in British overseas settlement in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand in the 19th century, is written with a novelistic flavor, using personal letters and journals to bring to life this group of talented but morally complex individuals whose exploits spanned the globe, and who remain an indelible part of British colonial history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

This Mottled World

1791–1827

CHAPTER ONE

The Matriarch and Her Sons

IN EARLY OCTOBER 1791, SEVENTEEN-YEAR-OLD Edward Wakefield returned to his parental home in Tottenham village, an hour’s coach ride north of London, and announced, ‘Mother, I am married!’1 Priscilla Wakefield’s reaction is not known but may have been only lightly admonishing, given the long-suffering equanimity of her Quaker disposition and the precocity of recent Wakefield marriages. Her own had been contracted with Edward senior when both were only 20, in 1771; his father had married at 21. Her daughter Isabella caused no grief, but Priscilla’s amiable patience was to be battered and tried her entire long life by the unexpected conjugal announcements of her sons and grandsons as they pursued a ‘fine irregular genius for marriage’2 that was finally suppressed only by trial and imprisonment.

Edward had taken up with Susannah Crush, the ‘bastard daughter of Robert Crush and Mary Galifant’;3 Crush was a yeoman farmer of Felstead in Essex. Edward described Susan as ‘The most beautiful woman I have ever known’. With a cascade of golden hair and ‘a soft angelic beauty … she was a model for a sculptor’.4 Gentle, unsophisticated and undemanding, Susan was not a woman of family and brought Edward no land or cash. Physical attraction, and his ‘ardent and enthusiastic disposition’,5 seem to have been the motives behind the marriage of the tall, good-looking teenager to a woman seven years his elder.

The connubial and domestic arrangements of Edward and Susan during the first years of their marriage are not recorded, but nearly two years elapsed before their first child, Catherine Gurney, was born in the parish of St Olaves, Old Jewry, City of London on 17 July 1793. Almost another three years passed before Priscilla noted in her journal on 20 March 1796, ‘Susan has a boy in London’,6 who was to be named Edward Gibbon. As she entered middle age, the tensions and stresses of coping with the demands and deficiencies of her growing extended family inform most entries in the journal that Priscilla kept for 20 years. ‘A plan in agitation for fixing Daniel [son] at Cowes. I fear his stability is scarcely equal to a situation so distant from the advice and counsel of friends’ (13 February). A few months later: ‘Drank tea with my Father who rapidly declines into the vale of years [70]. Age and infancy demand the attention of all closely connected’ (10 April).

Priscilla’s husband Edward (EW) ‘was a man the interest of whose fortune left him by his father was £3000 a year and his commercial and banking concern rated him as a man of the very first consequence… it must have had its weight with her parents and I suppose with herself.’ But EW had not inherited his father’s skills and luck in business and banking. ‘She bore his unexpected failure like a heroine and it has procured for her great respect ever since…’.7

The family suffered from recurring financial problems, a direct practical burden for Priscilla and the chronic prompt for many of her sons’ and grandsons’ actions in future years. She found solace, fortitude and life purpose in an enduring Quaker faith inherited from both her mother Catherine, granddaughter of Robert Barclay of Ure, the seventeenth-century Quaker apologist (and progenitor of the famous banking family), and from her father, Daniel Bell. After their marriage at the meeting house in Tottenham High Road, her parents had made a home at nearby Stamford Hill, 70 acres bordering the River Lea where a wharf and warehouse served Bell’s lifelong coal business. By 1796, Priscilla saw it as ‘Once the place of all my domestic joys, but now, alas! almost stript of all’ (22 July). As her widowed father neared the end of his life, she wrote on 25 July, ‘Could but age feel the advantage of continuing agreeable: what a delightful task to alleviate its miseries, as it is, it is an incumbent duty.’

Priscilla Wakefield’s Quakerism was actively and pragmatically philanthropic. She was no admirer of orthodoxy. At a Friends’ meeting she ‘mixed with numbers of those who think that extreme plainness of habit and address is essential to rectitude. I admire the simplicity of their manners, and the purity of their morals, but do they not sometimes deviate into mere formality and uniformity of habit?’ (6 September 1796).

Priscilla had been brought up in an environment less restricted than that of many Quaker families. Daniel had been fond of shooting, riding and fox-hunting, which were not at all compatible with Quaker practice since Friends were adjured ‘not to distress the creatures of God for our amusement’.8 Priscilla was said to be ‘fond of general society and some worldly amusements’:9 in December 1796, she went to London and ‘saw Macbeth. Delighted with the combined talent of Mrs Siddons and Kemble.’ But her piety and sense of propriety intervened as she added, ‘Why are these amusements polluted by dreadful intermixture of vice and profaneness.’

‘Her whole life was a devotion to benevolence!’ said her brother Jonathan.10 Already, in 1791, Priscilla’s determined kindness had established at Tottenham a charity for lying-in women. This was supported by annual subscriptions for which ‘one hundred and twenty poor married women are upon the average annually relieved with the use of linen during their confinement, and small donations of money’.11 In 1792 she organised the funding of a School of Industry where up to 66 girls could be taught reading, writing, sewing, knitting and some arithmetic. The girls were encouraged to enter domestic service and a guinea was paid each on completion of every three years’ continuous work as servants.12

Priscilla’s good works were unremitting: winter soup kitchens, a meeting to put a stop to the dangers of chimney sweeping, a manufactory to encourage spinning in the parish. But her most enduring philanthropic achievement was the introduction of savings banks. The concept was not new. Savings banks had been set up in Germany in the middle of the eighteenth century and later promoted by Jeremy Bentham, the Utilitarian,13 and Arthur Young, the agricultural reformer,14 of whom young Edward Wakefield was an enthusiastic disciple. But a bank in Britain first took practical shape as one of the functions of a Friendly Society for women and children that Priscilla Wakefield helped to establish at Tottenham in October 1798. Its objects included a fund for loans, ‘to prevent the use of pawnbrokers’ shops’, and a bank for the savings of the poor.

Initially, the Friendly Society bank operated only to encourage children to save, without the benefit of interest. As an agent of Providence and a representative of the Christian ‘kingdom within’, Priscilla’s moral purposes were clear: ‘It habituates the children to industry, frugality, and foresight; and, by introducing them to notice, it teaches them the value of character and of the esteem of those who, by the dispensation of Providence, are placed above them’.15 Priscilla’s charitable labours would never challenge the existing social and political order; she was a member of a non-conforming Quaker movement which, by the 1790s, ‘had prospered too much …. their hostility to State and authority had diminished to formal symbols’. Its continuing tradition of dissent ‘gave more to the social conscience of the middle class than to the popular movement’ for social and political reform.16

In 1804 the children’s fund was converted into the Charitable Bank, taking interest-earning deposits from adults, too. It was overseen by six wealthy trustees, ‘each responsible to the amount of 100 pounds for the repayment of principal and interest’.17 Priscilla and her son Edward persisted in a campaign to have savings banks more widely established under government guarantee. Edward’s association with the Secretary of the Treasury in 1817 helped at last in the passing of a savings bank act that procured government security for the deposits of trustees and managers. Security for all depositors – as savings banks spread throughout Britain – had to wait for Gladstone’s reforms 40 years later. (A proposed statue of Priscilla in Tottenham, to memorialise her as the savings bank founder, never eventuated.)

Priscilla’s Quaker philanthropy in aid of women and the poor was a late expression of what Pope called the ‘strong benevolence of soul’ that had gathered strength throughout the Georgian age. Her lying-in charity was one of the fruits of the medical reforms that saw more than 100 new hospitals and dispensaries established during the eighteenth century; her school was set up through the new Sunday Schools movement. Charity was the watchword of the new Puritans and Evangelists, and saw its most famous expression in William Wilberforce’s campaign to end the slave trade. ‘What pleasure it is,’ Priscilla wrote, ‘to confer happiness.’18

While charity and moral improvement lubricated middle-class consciences of the time, ideas of political and class reform were locked up during the generation-long military struggle with Revolutionary France and Napoleon. Republicanism, democracy and deism, those dangerous doctrines of the American and French Revolutions, stirred the working classes and were rigorously suppressed by the state. Tom Paine, advocating deism, republicanism, the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of women, had his seminal work, The Rights of Man (1791), banned and was forced to flee England when indicted for treason.

The friend and feminist counterpart of Paine was that so-called ‘hyena in petticoats’, Mary Wollstonecraft. Her 1792 book, Vindication of the Rights of Women, scandalised English society with its calls for sexual emancipation and equality of opportunity for women. With no political rights or access to power, Wollstonecraft did not need to be indicted for treason. The ridicule and contempt of the male establishment and the wave of disapproval and condemnation from the middle-class members of her own gender were censure enough.

Priscilla Wakefield’s commentary on Mary Wollstonecraft soon after her premature death in 1798 reveals how religious conviction and social conformity always informed her own best intentions. Because originality of Wollstonecraft’s genius ‘was not curbed by any regular cultivation, her faculties were left to expand by their own force’. Although this ‘probably contributed to leave her free from the usual fetters of prejudice’, it also ‘deprived her of the inestimable benefit of an early impression of religious principles’ so that she ‘deviated from those wholesome necessary restraints which the doctrines of re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE : This Mottled World

- PART TWO : Forward, Forward Let Us Range

- PART THREE : War to the Knife

- PART FOUR : A Suicide of the Affections

- EPILOGUE

- EXTENDED NOTES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- Plates

- About this Book

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Sort of Conscience by Philip Temple in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías históricas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.