- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

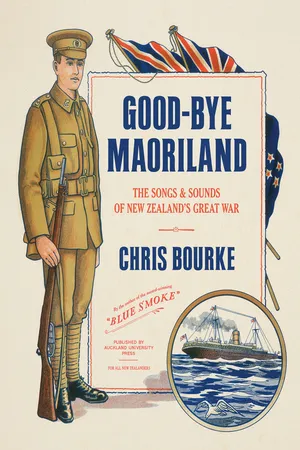

They left their Southern Lands, They sailed across the sea; They fought the Hun, they fought the Turk For truth and liberty. Now Anzac Day has come to stay, And bring us sacred joy; Though wooden crosses be swept away – We'll never forget our boys. – Jane Morison, 'We'll never forget our boys', 1917 Be it 'Tipperary' or 'Pokarekare', the morning reveille or the bugle's last post, concert parties at the front or patriotic songs at home, music was central to New Zealand's experience of the First World War. In

Good-Bye Maoriland, the acclaimed author of

Blue Smoke: The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music introduces us the songs and sounds of World War I in order to take us deep inside the human experience of war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Good-bye Maoriland by Chris Bourke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

SAY AU REVOIR AND NOT GOOD-BYE

On a balmy Sunday afternoon in late summer 1914, six months before the First World War, an audience gathered in Linwood Park, Christchurch. The entertainment was the Linwood Band, a brass ensemble of 22 local players. A march was the opening piece, and the reviewer for the Christchurch Sun was disdainful: the band’s performance was rough, its phrasing was non-existent and each set of instruments seemed to play in different pitches. ‘No two of them were in tune.’ A solo from the euphonium player sounded as if it was being played by a baritone; the soprano player cautiously felt his way through a cadenza. Only the cornet player showed competence. A selection from Verdi’s Macbeth was tragic, but not in the way the composer intended – ‘this was tragic enough to make one’s blood curdle’. The reviewer – whose pseudonym was ‘Maestro’ – offered some advice: ‘Try and get someone to help you tune the band up. Have scale practices. That is the only way to effectually cure the bad faults mentioned above, and then select easier pieces for programme work.’1

While Maestro was scathing, his review of an inconsequential concert by a lamentable band shows that musical life in New Zealand was vibrant during the antebellum period. All genres of music were available to the young society, whose population stood at 1.1 million as the war began. Most weeks in the main centres – and almost as frequently in the provinces – audiences could enjoy classical concerts and recitals, opera, vaudeville, civic functions, tours by international artists, pit orchestras at silent films, as well as amateur performances or recordings in the comfort of their living rooms. In Christchurch alone, there was enough brass band activity that the Sun provided Maestro the space to write a weekly column. Similarly, the Auckland Star ran lengthy reviews of the weekly recitals by the city’s official organist, J. Maughan Barnett.

Previews of vaudeville shows were also a regular feature of the newspapers in all the main centres. These shows usually featured visiting performers on the international circuit, brought here by entertainment impresarios such as Benjamin Fuller and J. C. Williamson. Singers of international renown made nationwide tours of New Zealand, among them John McCormack and Nellie Melba. A tour by a classical ensemble such as the young Cherniavsky Trio was eagerly covered by the press, especially the energetic, confrontational arts and music magazine, the Triad. Founded in Dunedin in 1893 the monthly managed to cover musical events throughout New Zealand – even after its head office moved to Sydney in 1913. The Triad was launched just as New Zealand was about to experience a ‘golden age of visiting opera companies and international music stars’.2

Larger towns boasted orchestral and operatic societies, choirs, brass bands, pipe bands and dance bands. Specialist retailers such as the Begg’s chain were on most main streets, selling instruments and sheet music, and acted as the heart of the music community. In gatherings public and private, music was vital. From the brass band at a civic reception to the ad hoc ensembles playing in living rooms, performance and melody helped bond the society.

Music-making at home revolved around the piano, and the proliferation of the instrument grew quickly in the years prior to the First World War. The peak came in 1916, when 40 per cent of households contained a piano. While this is less prevalent than the US (where, in 1925, a survey of 36 cities found a piano in 51 per cent of homes), it was much more expensive to acquire a piano in New Zealand. Whereas the US had a booming manufacturing industry, in New Zealand all but a few pianos were imported, lifting their cost. ‘Singing around the piano’ was far more popular than recitals, suggests historian Michael Brown: what appealed was the intimacy and emotions shared while performing in a living room. Marriage rates were rising, also – by 40 per cent between 1895 and 1904 – and with New Zealanders becoming more domestic and settled, so too did the sales of pianos increase.3

Lawrence Blyth, a private with the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, described himself as unsophisticated when he enlisted at eighteen. Growing up in Canterbury, social life centred on the family. ‘It was all very modest, round the family piano where we played and sung all the old songs. We went to church and Sunday school. No, we led a fairly quiet life, and then to be picked up and dumped into a war and to experience all those things, it certainly is a dramatic change in one’s life.’4

Grace Brake grew up on a King Country farm, one of six daughters whose father bought a piano so they could socialise at home. Young men came on Sundays for sing-songs and dances in the living room. Before the war, the selections were usually ‘sentimental favourites’ such as ‘Please Give Me a Penny, Sir’ (a nineteenth-century song turned into a Red Cross fundraiser during the war), ‘Don’t Go Down the Mine, Father’, ‘Mother Machree’, ‘Kathleen Mavourneen’, ‘Because’, ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ and ‘She is Far From the Land’.5

The pre-war period saw the worldwide music industry going through one of its periodic revolutions. In Britain and New Zealand, sales of sheet music, gramophones and pianos boomed; songs in the new ‘ragtime’ style championed by Irving Berlin were infiltrating the polite ballads favoured by performers such as John McCormack and Caruso, which evolved from lieder rather than folk sources. ‘Every respectable household… wanted a piano in the parlour’, said Lyn Macdonald, and there were also uprights in schools, church halls, pubs and clubs.6

As well as making their own music, New Zealanders increasingly enjoyed listening to recordings of the world’s greatest talents. Record stores were widespread, with chains such as Begg’s, the Talkeries shops, the Dresden Piano Company and the Anglo-American Music Stores selling cylinders and discs, and the wind-up machines on which to play them. The Talkeries chain was founded in 1901, with stores in many main centres including Wellington, Masterton, New Plymouth and Dargaville. While the availability of recorded music would lead to a decline in domestic music-making, selling musical instruments was the core business for Begg’s, and a sideline for the Talkeries chain.

The Talkeries was a retailer of recordings, phonographs and gramophones, with several branches in New Zealand before the war. This is the interior of the Masterton branch, c. 1909. A sign reads: ‘Kindly Note: phonograph records will be rendered on request at a charge of 2d each. Melba, Crossley and Caruso Operatic Records 6d each. In event of a purchase being made there will be no charge.’ PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN. ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, WELLINGTON, 1/2-043062-F

The Anglo-American Music Stores had branches in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. Their approach to sales was aggressive: they advertised widely and regularly marked down their product range. In 1914 they advertised that 1000 watches, necklaces, chains, medals and gramophone records would be given away free at the Wellington store.7 The company exploited the ragtime fad, being quick to import discs of the latest hit songs, and offering a range of sheet music starting at 6d per song.8 In 1914 the Wellington branch advertised several new songs by Irving Berlin, who dominated the sheet-music market. For 1/6 pianists could buy Berlin’s ‘When the Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam’, ‘Stop! Stop! Stop!’ and ‘Come Over and Love Me Some More’, as well as a saucy summer hit for the Australian swimming star Annette Kellerman: ‘Come Take a Dip in the Deep With Me’.9

Ragtime had been enjoyed in New Zealand since January 1900 when Dix’s Gaiety Company included Clarinda – a short ragtime opera – in its variety show at Auckland’s Town Hall.10 The style became an increasingly regular feature in variety shows, and New Zealand adopted the music of Irving Berlin with gusto. In 1911, two years after his greatest success, ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, Berlin almost eclipsed it with ‘Everybody’s Doing It’, a song so popular its title became a catch-phrase, used in headlines, advertisements and everyday speech. When the Vatican initiated a crusade against the tango ballroom dance – declaring it ‘subversive of purity’ – the Auckland Star’s headline was: ‘Vatican Vetoes Tango: But Everybody’s Doing It’.11 The song was on sale in New Zealand soon after Berlin wrote it, and quickly heard throughout the country. In June 1913 the Wellington Gas Company Orchestra performed it as a two-step at a dance to benefit the Missions to Seamen.12

The dance era had arrived and, wrote Auckland music historian Dave McWilliams, it needed ‘tuneful music’. New dances included the Gaby glide, hesitations and the tango. Besides ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, other recent hits in New Zealand included ‘Oh, You Beautiful Doll’ and ‘Yiddle on Your Fiddle’.13 In July the Wellington branch of Begg’s music store was advertising ragtime records for 3/6, with titles including ‘Everybody’s Doing It’, ‘Gaby Glide’, ‘The Wriggly Rag’ and the ‘Turkey Trot’, as well as vocal numbers by Nellie Melba, Clara Butt, Peter Dawson, John McCormack and others.14

‘The world and his wife had gone dancing mad, turkey trotting, bunny hugging, balling the jack’, wrote Tin Pan Alley historian Ian Whitcomb.15 In Wellington in 1913, students from Victoria University College burst into a capping ceremony in the Town Hall ‘dressed as Maoris’ and began to dance the ‘Turkey Trot’ and perform a haka, accompanied by ragtime on the piano. The ceremony was forced to reconvene in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Say au revoir and not good-bye

- Chapter Two: Bands of brothers

- Chapter Three: Music in khaki

- Chapter Four: Help the lads who will fight your fight

- Chapter Five: We shall get there in time

- Chapter Six: Waiata maori

- Chapter Seven: Kiwis, tuis and pierrots

- Chapter Eight: Dawn chorus

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright