- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

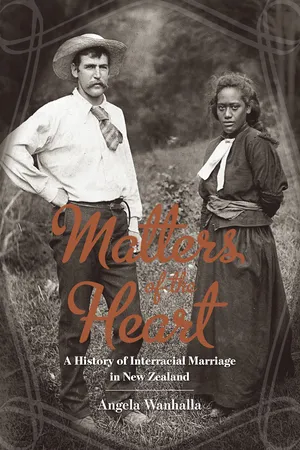

About this book

From whalers and traders marrying into Maori families in the early 19th century to the growth of interracial marriages in the later 20th,

Matters of the Heart unravels the long history of interracial relationships in New Zealand. It encompasses common law marriages and Maori customary marriages, alongside formal arrangements recognized by church and state, and shows how public policy and private life were woven together. It also explores the gamut of official reactions—from condemnation of interracial immorality or racial treason to celebration of New Zealand's unique intermarriage patterns as a sign of its progressive attitude toward race relations. This social history focuses on the lives and experiences of real Maori and Pakeha people and reveals New Zealand's changing attitudes to race, marriage, and intimacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Matters of the Heart by Angela Wanhalla in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Australian & Oceanian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

Marriage in Early New Zealand

Contradictory accounts of interracial relationships characterise their history in New Zealand, beginning with the very first meetings between Pākehā and Māori in the decades before 1840. Cross-cultural intimacies forged during the period 1769 to 1840 have been variously characterised as fleeting and casual encounters, temporary or seasonal marriages, a form of sexual hospitality, a feature of an established ‘sex industry’, or monogamous relationships based on affection following the forms and conventions of Māori marriage traditions. Intimate relationships certainly encompassed a great variety of forms and practices in early meetings, and these were largely reflective of the differing circumstances under which interracial sex could take place prior to 1840, as well as the intensity and duration of cross-cultural contact over that period. This diversity was not always obvious to visitors, who tended to apply western understandings of morality and marriage to indigenous cultures. To them, Māori marriage customs were a commercial transaction lacking in emotion or romantic love, while the acceptance of pre-marital sex fostered a view that fathers, brothers and uncles traded women for goods.1 Europeans saw an absence of a marriage rite and so-called ‘easy divorce’ as further evidence of Māori sexual immorality, going so far as to describe interracial relationships as prostitution.

Into this world entered traders and sailors, who settled onshore on a semi-permanent basis, and built up intimate ties with Māori women. Their work in the extractive, resource-based timber, shipping and whaling industries was connected to a trade in goods, as well as in women’s bodies. As we shall see, while several different forms of marital patterns existed alongside each other in the decades prior to 1840, the most common form was temporary marriage, which lasted as long as the ship was in port, and tended to be monogamous in character and affectionate in nature. A ‘sex trade’ and love matches could exist within the same culture, and Māori used both to govern newcomers, but they also welcomed formal alliances through marriage, in a manner that followed recognisable local practices and rituals. By 1840, when around two thousand mostly male newcomers had settled on the land and created communities, a particular marriage culture had evolved that followed Māori marriage customs, but also drew upon practices from the maritime world, which were more civil than religious in form and spirit.

Voyagers and visitors

From the moment Poverty Bay was sighted by James Cook and his crew on 6 October 1769, newcomers associated Māori sexual behaviour with a set of ‘degrading’ practices, including polygamy and ‘easy divorce’. During a six-month circumnavigation of New Zealand’s coastline, Cook and his crew spent 56 days onshore. The scientific objectives of the voyage required long periods at anchor to allow for the gathering of data, which happened with regularity, and the time on land offered ample opportunity to observe local women and sexual customs.2 These early meetings were tentative, and cautious, and were characterised by sexual propriety and decency, with visitors careful to follow the customs of the local people. Joseph Banks observed that

such of our People who had a mind to form any connections with the Women found that they were not impregnable if the consent of their relations was asked, & the Question accompanied with a proper present it was seldom refused, but then the strictest decency must be kept up towards the Young Lady or she might baulk the lover after all.3

Women were cautious of the strangers.4 At Tolaga Bay, Banks described the local women ‘as great coquets as any Europeans could be, & the Young ones as skittish as unbroken fillies’.5 Young women were able to exert a measure of sexual freedom, but married women were off limits. French explorer Marion du Fresne, who spent April to July 1772 in the Bay of Islands and communicated with local Māori in the Tahitian language, was warned against them.6

Despite some uncertainty, communities of Māori were interested in these strangers and their goods, and were hospitable and willing to interact and to trade. But while men could arrange for a measure of comfort if they followed local custom, not all prospective suitors were successful. When anchored at Totaranui in February 1770, Banks observed that

One of our Gentlemen came home to Day abusing the Natives most heartily, whom he said he had found to be given to the detestable vice of Sodomy; he, he said, had been with a family of Indians [Māori], & paid a price for leave to make his addresses to any one Young Woman they should pitch upon for him; one was chose as he thought who willingly retired with him, but on examination prov’d to be a Boy, that on his returning & complaining of this another was sent who turned out to be a Boy likewise; that on his second complaint he could get no redress but was laught at by the Indians: Far be it from me to attempt saying that that Vice is not practised here; this however I must say, that in my humble opinion this Story proves no more than our Gentleman was fairly trick’d out of his Cloth, which none of the Young Ladies chose to accept of on his terms, & the Master of the family did not chuse to part with.7

Historian Chris Brickell cautions against use of this as evidence of Māori acceptance of homosexuality, but this intimate moment does demonstrate some of the rules, community restrictions and protocols placed upon sexual behaviour.8 Premarital sex was allowed, but it had to be sanctioned, carefully negotiated and a gift given that was commensurable with the rank of the young lady. The terms of negotiation were also clearly set by Māori, not the newcomers, even if this was not clear to the suitor at the time.

While some travellers emphasised Māori women’s modesty and decency, others routinely asserted their immorality. In 1769 French officers on the Saint Jean Baptiste found the dances of welcome, an important part of hospitality, ‘indecent’ in gesture and movement, designed to ‘entice’ and ‘stimulate the indifference of the European spectators’.9 When the Resolution anchored at Totaranui in 1773, Cook thought the women’s displays of indecency and immodesty were encouraged by his crew, who ‘are the chief promoters of this vice, and for a spike nail or any other thing they value will oblige their wives and daughters to prostitute themselves whether they will or no and that not with the privicy decency seems to require, such are the consequences of a commerce with Europeans’.10 In 1778 the HMS Adventure anchored at Queen Charlotte Sound. Again, a variety of encounters with women took place, encompassing modesty and caution on the one hand and sanctioned sex on the other.11 Transactional sex seemed to be available too, as the women ‘offer’d themselves for sale with as much ease & assurance as the best Strand walker in London, and indeed during our Continuance there, we found them the cheapest kind of traffick we could deal in’.12

To some observers this exchange of goods equated to a sex trade, while others regarded these transactions as forms of marriage in which intimate and affective bonds were sometimes forged. One sailor on the Discovery formed a mutual attachment with a young woman that was characterised by little verbal communication but much tender tactility and a desire for co-habitation.13 The scientist George Forster, who was on board the Resolution in 1773, noted how one young woman was ‘regularly given in marriage by her parents to one of our shipmates’ and that she was ‘faithful to her husband’ in ‘rejecting the addresses of other seamen, professing herself a married woman’.14 John Ledyard, corporal of the marines on the Resolution, discovered that one of his men had decided to become tattooed, because ‘he was conscious that to ornament his person in the fashion of New Zealand would still recommend him more to his mistress and the country he was in’.15 When The Prince Regent was about to leave northern New Zealand in 1820, after ten months in the country, the women on the ship were ordered off after having ‘lived on board and with the same persons since we returned from Shukehanga [Hokianga]. They imitated as far as they could the English manner of dress, conformed themselves to English customs, and showed as much regard for their protectors as they could for their real husbands.’16 Some men chose to desert ship for their partner. When Robert Hill’s vessel was at anchor at Whangaroa, he absconded and was welcomed into the community. On being recaptured, he was placed in custody but disappeared again. He was eventually found in a hut embracing his lover, ‘crying and sobbing in the same melancholy manner as is customary with these islanders after a separation of any length of time’.17

As more ships visited the Bay of Islands, and more of them stayed for longer periods of time, the character of interracial relationships changed and monogamy became a defining feature of the accounts.18 In May 1820 the Dromedary and Coromandel arrived in the Bay of Islands, carrying missionaries as well as trade goods.19 Anglican missionaries, by this time firmly established in the northern reaches of the country, linked women’s supposed sexual degradation to Māori men’s desire for muskets.20 Ships officers and crew had a very different experience. In his statement that ‘several women lived on board’ the Dromedary, Alexander McRae pointed to the practice of temporary marriage.21 Dr Fairfowl, who was also on the Dromedary, witnessed chiefs ‘offer[ing] their sisters and daughters for prostitution’, but noted that they ‘expect a present in return’.22 One of the core features of Māori marriage is the gift-exchange, but this practice incited contradictory interpretations of marital culture when it was witnessed by outsiders. Where some visitors saw it as evidence of the cementing of an affectionate bond, others saw it as prostitution. Gift-exchange was a normal rite followed in Māori marriage custom, and its presence in the establishment of these short-term relationships suggests that they were socially sanctioned and were limited to unmarried women.

Short-term gain made through temporary marriages in the form of goods was acceptable as long as it did not affect the future prospects of a young woman. In one case, the son of a master of a vessel was publicly accused of attempting to seduce the sister-in-law of a chief.23 She claimed that ‘one of the sailors had given her a nail, and promised her another, if she would consent to grant him certain favours; but she refused, and would not by any means be prevailed upon, telling him, she was the wife of another man, and consequently tabooed [tapu]. She confessed, however, that she kept the nail the man had given her; but persisted in declaring that no criminal connection had taken place between them.’24 The offer or acceptance of goods did not equate with a sanctioned relationship in this instance, and nor did it always in fact indicate that a sexual encounter had occurred.

Although many observers regularly portrayed Māori women as subject to coercion from men to have sex, it appears that they had a certain degree of autonomy in entering these relationships: they could reject offers, they could encourage a relationship, and they could also negotiate personal and material conditions before committing to a partner. However, it is difficult to make generalisations about the degree to which women had control over these encounters,25 as the available archives, written mainly by elite white men...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface: Matters of the Heart

- 1. Marriage in Early New Zealand

- 2. Missionaries, Morality and Interracial Marriage

- 3. The Affective State

- 4. Wives or Mistresses?

- 5. Race, Gender and Respectability

- 6. The ‘Science’ of Miscegenation

- 7. Modern Marriage and Māori Urbanisation

- Epilogue: Marriage and the Nation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- photos

- Copyright Page

- Backcover