eBook - ePub

Entanglements of Empire

Missionaries, Maori, and the Question of the Body

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Entanglements of Empire explores the political, cultural and economic entanglements and irrevocable social transformations that resulted from Maori engagements with Protestant missionaries at the most distant edge of the British empire. The first Protestant mission to New Zealand, established in 1814, saw the beginning of complex political, cultural, and economic entanglements with Maori. Entanglements of Empire is a deft reconstruction of the cross-cultural translations of this early period. Misunderstanding was rife: the physical body itself became the most contentious site of cultural engagement, as Maori and missionaries struggled over issues of hygiene, tattooing, clothing, and sexual morality. In this fascinating study, Tony Ballantyne explores the varying understandings of such concepts as civilization, work, time and space, and gender – and the practical consequences of the struggles over these ideas. The encounters in the classroom, chapel, kitchen, and farmyard worked mutually to affect both the Maori and the English worldviews. Ultimately, the interest in missionary Christianity among influential Maori chiefs had far-reaching consequences for both groups. Concluding in 1840 with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the new age it ushered in, Ballantyne's book offers important insights into this crucial period of New Zealand history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Entanglements of Empire by Tony Ballantyne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Australian & Oceanian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One EXPLORATION, EMPIRE, AND EVANGELIZATION

In order to understand the debates and transformations enacted by the meeting and entanglement of the very different bodily cultures of British evangelical missionaries and Māori, we need to locate these engagements within the broader framework of the cross-cultural relationships produced out of the European intrusion into the southern Pacific. In this chapter I sketch the encounters and entanglements that brought Māori and Europeans into connection and New Zealand’s incorporation into the discourses and economic networks of the British empire during the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth. The four decades of imperial endeavor in this region that predated the establishment of the CMS mission in 1814 set the key parameters that shaped the ways in which Britons imagined both New Zealand’s place within the empire and the nature of Māori society. Most important, this history of imperial exploration and commerce encoded Samuel Marsden’s plan for the New Zealand mission and his vision of the types of social change that missionaries could enact. Thus, rather than follow historians, such as Andrew Porter and Brian Stanley, who have suggested that the evangelical ethos placed missionaries outside the mainstream of British imperial culture, I highlight Marsden’s significant debt to an imperial set of discourses on the nature of “civilization” and his very real reliance on imperial commercial networks and the instruments of the colonial state in New South Wales.

In rejecting a simple “religion versus empire” formulation, I return missionary institutions to the broader field of empire, to what Mrinalini Sinha has termed the “imperial social formation.”1 This is not to argue for an undifferentiated reading of empire—which would see missionaries, merchants, and military men as part of an unified imperial project—for we must not conflate the aims and outcomes of missionary activity with the imperial visions of the Admiralty, Colonial Office, London merchants, or the colonial state in New South Wales simply because they share a common “British heritage.” Rather, seeing missionary activity within an imperial framework allows us to strike a balance between an awareness of the particularity of the cultural vision underpinning the foundation of the CMS mission in New Zealand and acknowledgment of the ways in which Marsden’s project drew on an earlier history of British activity in the Pacific and utilized the knowledge, institutions, and commercial structures produced by this activity.

With these aims in mind, I first examine the European “discovery” of “New Zealand,” arguing that European understandings of this large archipelago of islands and its inhabitants were underpinned by interest in the Pacific as a sphere for empire-building. Much of the recent work on encounters between Māori and Europeans in the late eighteenth century and earlier nineteenth has seen these cross-cultural engagements as anticipating the bicultural social formations that have become central to state policy and national identity in New Zealand.2 Rather than using the dominant ideology of the late twentieth-century nation state as an analytical lens, I place greater emphasis on the significance of imperial desire—for knowledge, land, resources, and strategic advantage—in bringing Europeans to New Zealand’s shores and on the role of this quest for power in framing both New Zealand and Māori within a discourse of “imperial potentiality.” Building on this argument, I examine the importance of the region in British evangelical thought and the ways in which missionary activity in New Zealand shaped imperial discourses and structures. After briefly sketching the place of the Pacific in the writings of influential English evangelicals in the late eighteenth century, I focus on Samuel Marsden’s development of a plan for a mission to Māori. My reading of Marsden shows his dependence on imperial commercial networks, political structures, and discourses on cultural difference. I place particular stress on the importance of both labor and consumption in shaping the very divergent readings he developed of Māori and Aboriginal cultural capacity. As well as locating Marsden’s thought within these discourses on civilization and improvement, I suggest that the personal relationships that leading Māori rangatira (chiefs)—such as Te Pahi and Ruatara—established with Marsden were crucial in convincing him of Māori potential and of the viability of a mission to New Zealand.

So while viewing missionary endeavor within the “imperial social formation” allows us to trace what Stoler and Cooper termed the “tensions of empire” or what Jeffrey Cox has seen as “imperial faultlines”—the fractures, points of tension, and competing visions of empire articulated from within the colonizing culture—the history of missionary activity in New Zealand also has to be seen as standing at the juncture of imperial history and Māori history.3 Although it was Marsden’s debt to post-Enlightenment and evangelical thought that encouraged him to believe that Māori were capable of embracing the “Gospel of Civilization,” the genesis of the mission must be also read within the trajectories of Māori history.4

Not only was Māori patronage and protection essential to the establishment of the mission, but rangatira initially drove the development of these cross-cultural engagements. The efforts of Bay of Islands’ rangatira to foster missionary activity occurred within two main contexts. First, by the early nineteenth century, Māori leaders in the far north were aware of the opportunities for enhancing their wealth and mana (status, power, authority) that contact with Europeans presented. The plants, animals, and tools introduced by Europeans were highly valued, not simply because they were “new,” but because they aided the chiefs in discharging two of the essential responsibilities of chieftainship more effectively: the production of food and conducting war. Second, the very specific configuration of indigenous political power in the early nineteenth century encouraged these chiefs to place particular value on relationships with Europeans, including missionaries. From the late eighteenth century, two competing alliances of kin-groups were struggling to establish their economic and political hegemony over the Bay of Islands’s fertile fields, rich estuaries, and sheltered bays.5 A complex series of military campaigns and reprisal raids were a central feature of this political contest, and within this context, Europeans—with their access to metal, new weapons, and food items—became a potent new factor within the complex and tense terrain of indigenous politics.

Exploration and Empire

The rivalries in the Bay of Islands were the outcome of long histories of migration, settlement, intermarriage, and competition over valued resources. These processes were driven by entirely local forces: for the six or seven centuries that had passed since the north of Te Ika a Māui (New Zealand’s North Island) was settled by Pacific peoples from the region that we now describe as East Polynesia, these communities had been isolated from the rest of the Pacific and the rest of the world. Their life and identity were invested in the local land-and seascapes, and their possession of this new homeland was undisturbed by outsiders.

Most important, Te Ika a Māui remained a mystery to Europeans. That is not to say that Europeans did not contemplate the southern oceans, but rather that their actual knowledge of the Pacific Ocean remained negligible. At least since the time of Ptolemy (around 150 A.D.), the geographers, historians, and theologians of the Mediterranean world and Europe speculated on what might lie to the south of the known world. Ptolemy himself suggested that an “unknown land” existed to the south of Eurasia, and he believed that this landmass was large enough to “enclose the Indian sea.” This vision of a large and undiscovered continent persisted in European geographical thought during the medieval period and was elaborated during the Renaissance. The extension of Europe’s commercial and imperial reach into the Atlantic and its discovery of direct maritime routes around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean expanded European knowledge of the world. Within this context of exploration, the growth of cartography, and European empire building, the notion of an unknown southern continent was consolidated within European thought. It was believed to be large; it had to match the northern landmasses of Europe, Asia, and the recently “discovered” North America in order to produce the symmetry and order that were discernible in the physical world.6

The southern continent—Terra Australis Incognita, as it was widely known—was both an integral element in early modern European geography and a potent imperial fantasy. As the value of long-distance trade in spices and Asian finished goods (such as silk and porcelain), the profits made from slave-trading, and the economic importance of new world plantations and mines transformed European states and their economies, European powers were increasingly alive to the commercial and strategic benefits of empire-building. The fevered imperial imaginations of geographers, merchants, and royal advisors imagined Terra Australis as an untapped treasure house, over-flowing with precious stones, gold and silver, spices, and as yet undiscovered commodities of value. This imperial fantasy was fed by the first expedition of Alvaro de Mendaña (which discovered the Solomon Islands, in 1568) and his second expedition with Pedro de Quirós (which discovered the Marquesas and the Santa Cruz Islands, in 1595). These discoveries were tantalizing, convincing the Spanish explorers that they had discovered the edges and outliers of a substantial landmass roughly equivalent to Europe and Asia in size.7

While Quirós pursued this phantom again in a 1605–6 expedition that discovered the New Hebrides, other European powers were also drawn to this quest. In fact, from the middle of the sixteenth century, English proponents of empire had advocated expeditions to search for the southern continent and enthusiastically imagined an empire greatly enriched by the wealth of Terra Australis.8 But it was the Dutch who took the lead in this project. Where the Iberian powers and Britain’s East India Company had well-established commercial enclaves in the Asia-Pacific region at the start of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were keen to establish a secure presence in the “East Indies” and its adjoining territories. In 1606 officials of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (the voc, or Dutch East India Company) in Bantam sent the Duyfken, under the command of Willem Janzsoon, to search for “east and south lands,” initiating a sequence of voyages that revealed much new detail of the islands of southeast Asia and the coastline of northern and western Australia.9

Eager to expand their commercial domain, the council of the voc in Batavia sponsored another voyage in search of the “Unknown South-land” in 1642. In their instructions, the council emphasized their hope that the voyage would result in a discovery equivalent to that of the Americas, which had allowed the “kings of Castile and Portugal” to possess “inestimable riches, profitable tradings, useful exchanges, fine dominions, great might and powers.”10 The voc dispatched the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen, under the command of Abel Janszoon Tasman, to explore the southern latitudes of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, advising him to chart in detail any newly discovered lands and to ascertain what valuable commodities and resources were to be found there.11 The expedition set out from Batavia, paused in Mauritius, and from there, after the vessels had been refitted, sailed southeast. In late November 1642, the explorers “discovered” the landmass now known as Tasmania, which they named “Anthonij Van Diemens Landt,” after the governor of Batavia. After making brief forays ashore and skirting the coast of Tasmania for several days, the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen sailed eastward in search of further evidence of the “South-land.”

On 13 December 1642, this Dutch expedition sighted “a large high elevated land” as they approached the west coast of the landmass that Māori knew as Te Wai Pounamu (the home of Pounamu), what is now known as New Zealand’s South Island.12 The Heemskerck and the Zeehaen sailed northeast along the coastline, on 18 December 1642 rounding the large twenty-mile-long sandspit at the northern tip of the island, a spit which guarded the entrance to a wide open bay. This bay, which is now named Golden Bay, was known as Taitapu (the Tapu Coast) by the Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri people, who had migrated to the northwest of Te Wai Pounamu from their original tribal home in the central part of Te Ika a Māui (the North Island).13

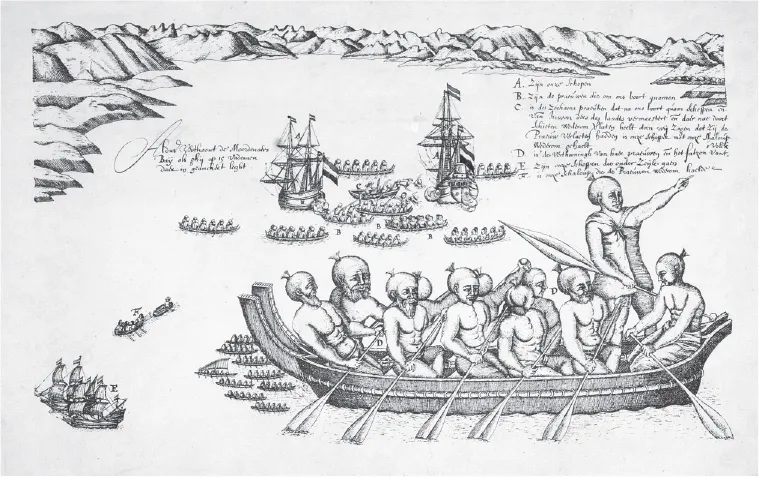

FIGURE 1.1 Gilsemans, Isaac, fl 1630s–1645?. A view of the Murderers’ Bay, as you are at anchor here in 15 fathom (1642). Abel Janszoon Tasman’s Journal. Amsterdam, Friedrich Muller & Co, 1898. Ref: PUBL-0086-021, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

The encounter between Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri and the Dutch was tense and full of miscommunication: the haka (action dance) and ritual challenges that Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri issued to the Europeans were met with warning cannon fire. Violence erupted when a large waka (war canoe) rammed the cockboat of the Zeehaen, knocking one sailor overboard, and the warriors swiftly killed three of the sailors and fatally wounded another (see figure 1.1). After hauling one of their victims onto the waka, the warriors quickly paddled to shore, avoiding the gunfire from the Heemskerck. Both ships subsequently opened fire on the eleven waka that had set out toward the Dutch vessels and then set sail.14 The Zeehaen and the Heemskerck skirted up the west coast of the North Island, only pausing briefly in the Three Kings group, off the northern tip of the North Island. The crew of the cockboat that was sent ashore on “Great Island” in this group encountered people who resembled those they had met in Golden Bay, but these northern people were distinguished by their great height and extremely long stride. These giant men were well-armed and pelted the Dutch sailors with stones (see figure 1.2).15 The Dutch beat a hasty retreat and Heemskerck and the Zeehaen sailed off into the Pacific.

On the basis of this initial engagement, this chain of islands, which Tasman named Zeelandia Nova, seemed to have little imperial potential. In clinging to the west coast, the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen got only a partial view of the islands’ true geography: they saw abruptly rising mountains, few harbors, and beaches pounded by heavy surf, while the sheltered anchorages, coastal plains, and rich estuaries of the east coast remained out of view. Nor were there any signs of the great wealth that they hoped to find on the “Southland.” Most important, the local population appeared aggressive, int...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Bodies in Contact, Bodies in Question

- Chapter One: Exploration, Empire, and Evangelization

- Chapter Two: Making Place, Reordering Space

- Chapter Three: Economics, Labor, and Time

- Chapter Four: Containing Transgression

- Chapter Five: Cultures of Death

- Chapter Six: The Politics of the “Enfeebled” Body

- Conclusion: Bodies and the Entanglements of Empire

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- Backcover