- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

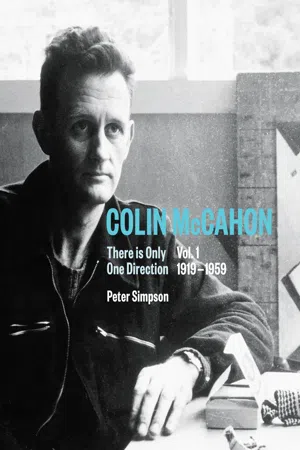

The first of an extraordinary two-volume work chronicling forty-five years of painting by New Zealand's most important artist, Colin McCahon. Colin McCahon (1919–1987) was New Zealand's greatest twentieth-century artist. Through landscapes, biblical paintings, abstraction, the introduction of words, and Maori motifs, McCahon's work came to define a distinctly New Zealand modernist idiom. Collected and exhibited extensively in Australasia and Europe, McCahon's work has not been assessed as a whole for thirty-five years. In this richly illustrated two-volume work, written in an accessible style and published to coincide with the centenary of Colin McCahon's birth, leading McCahon scholar, writer, and curator Peter Simpson chronicles the evolution of McCahon's work over the artist's entire forty-five-year career. Simpson has enjoyed unprecedented access to McCahon's extensive correspondence with friends, family, dealers, patrons, and others. This material enables us to begin to understand McCahon's work as the artist himself conceived it. Each volume includes over three hundred illustrations in colour, with a generous selection of reproductions of McCahon's work (many never previously published), plus photographs, catalogue covers, facsimiles, and other illustrative material. This will be the definitive work on New Zealand's leading artist for many years to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction by Peter Simpson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Modern Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SOUTHERN BEGINNINGS, 1919–36

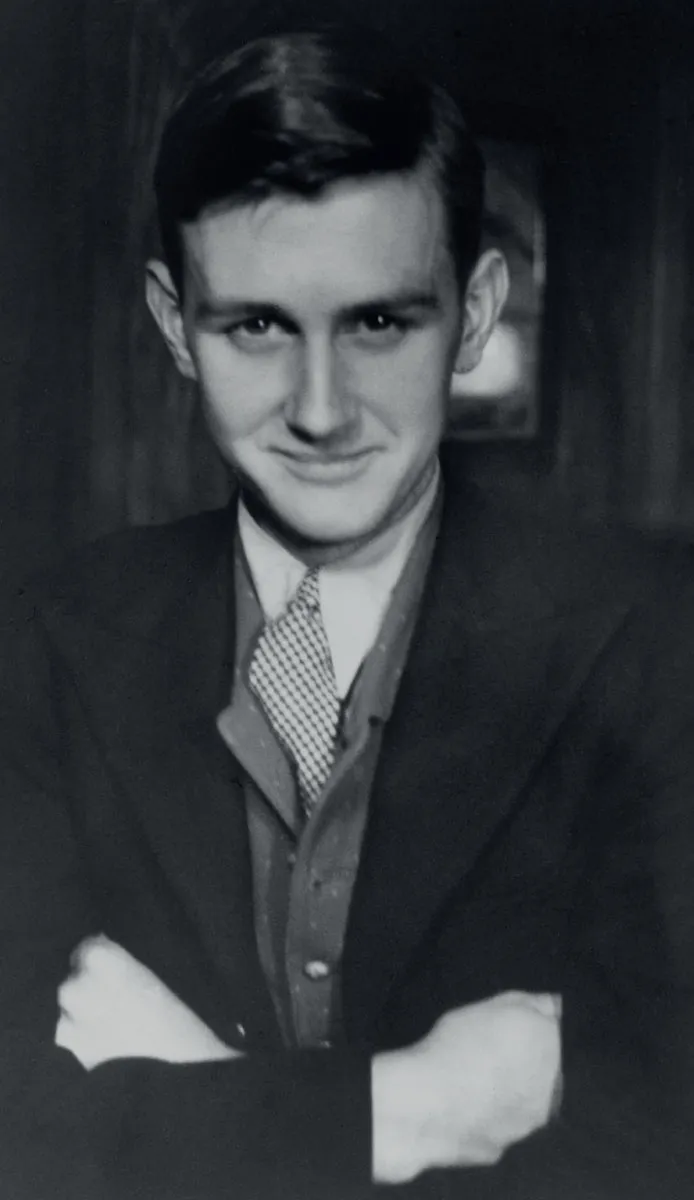

Colin McCahon, aged about eighteen, c. 1936–37.

E. H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Colin McCahon Artist File

‘I was very lucky and grew up knowing I would be a painter. I never had any doubts about this.’ So Colin McCahon wrote in his autobiographical notes for the catalogue of Colin McCahon: A Survey (1972) – the largest exhibition of his work held during his lifetime. The passage continues: ‘I knew it as a very small boy and I knew it later. I know it now when it is too late to turn back and I only wish I were a better painter.’1 Evident here is the strong sense of direction and continuity, and the striving to do better, which his life as a painter displayed from beginning to end.

Family background and environment

McCahon’s certainty about his vocation was undoubtedly stimulated by the art-friendly environment into which he was born. His maternal grandfather, William Ferrier, was a professional photographer and amateur painter; his parents, Ethel and John McCahon, were gallery-attending art enthusiasts who encouraged their precocious son’s ability by exposing him to exhibitions, books and painting lessons. His mother recalled Colin’s gifted manual prowess as a child: ‘at the age of eight, he could do two drawings simultaneously, one with each hand’.2

Colin John McCahon was born on 1 August 1919 in Timaru, on the Pacific coast of the South Island, where his mother, Ethel (née Ferrier), had grown up; she had returned from Dunedin where she and her husband were living to her parents’ house for the birth of her second child. Colin had an older sister, Beatrice, a teacher (born 1918), and a younger brother, Jim, a scientist (born 1921).

Colin’s father, John Kernohan McCahon (1884–1963), the youngest in a large family, was a businessman (commercial traveller, company manager) of Irish Protestant descent who during Colin’s youth was manager of Austin Motors in Dunedin. Writing to his Wellington dealer, Peter McLeavey, Colin once reported that his father had travelled with a future brother-in-law to North America and Europe before World War I and that he was the only boy in his family: ‘8 girls & then poor father. All the sisters married “well” – Father married a poor painter-photographer’s daughter.’3 Several of his McCahon relatives, according to this letter, were ‘in the medical business … Another aunt of mine was the first – or near first – school doctor in N.Z. She was small & Irish dark …’.4 Colin’s parents married in 1915. He always addressed them in letters as ‘Mother’ and ‘Father’ which suggests a middle-class home environment and customs as compared to most New Zealanders’ more common ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’.

The McCahon family, c. 1936–37: back row, Jim and Colin; front row, Beatrice, Ethel and John, from file copy print, photograph taken by E. A. Phillips.

Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Ethel Beatrice McCahon (1888–1973), Colin’s mother, was of largely Scottish descent, her father being Edinburgh-born William Ferrier (1855–1922) who came to New Zealand with his widowed father David, a bookseller, as a fourteen-year-old in 1869; William’s mother, Catherine Lowe (daughter of a Congregational minister), was also Scottish-born. In 1886 in Ōamaru, William married Eva Beatrice Cunninghame (c. 1863–1946, known to her McCahon grandchildren as ‘Gaggie’), fourth child of Sarah and Thomas Cunninghame. Active in the Wesleyan Church and superintendent of the Sunday school, Thomas was treasurer and town clerk of Ōamaru, a native of Dublin in Ireland who came to New Zealand in 1878; his wife Sarah died at forty-six in 1884.

Maori Hill School, Dunedin, standard one class, 1926; Colin McCahon is in the back row, third from right.

Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago, AG-262-8/01/001, Maori Hill School records

William Ferrier established a photographic business in Timaru in 1881 (he had previously worked in studios in Christchurch and Ōamaru, where presumably he met his wife, Eva); he was also a competent amateur painter in oils and watercolours. William and Eva Ferrier had eight children, after one of whom Colin was named – Gilbert Colin Cunninghame Ferrier, an engineer and bridge designer, who was training in England to be an architect when World War I war broke out. He was a second lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and was killed at Ypres, Belgium, in 1914 aged twenty-four. Within the family, Colin was thought to have inherited his uncle’s talents. Colin’s ethnic inheritance was therefore largely Celtic – Irish on his father’s side, largely Scottish on his mother’s – with active Protestants in both families.

McCahon later wrote about his maternal grandparents’ house in Timaru in the essay he contributed to the series ‘Beginnings’ in Landfall in 1966:

My grandfather William Ferrier was both a photographer and a landscape painter in water colour. We grew up with his paintings on the walls, and at holiday times visiting my Grandmother’s house at Timaru (I don’t think I ever met my Grandfather) we lived in rooms hung floor to ceiling with water colours and prints. Once, suffering from mumps, I think it was, I spent a time confined to bed in what had been my Grandfather’s dark room: red glass in the window, and paints and brushes, a palette, in shallow drawers…. [A]nd so it was that having met the ‘finished’ work both in Timaru and Dunedin I now met the sacred materials of ‘art’.5

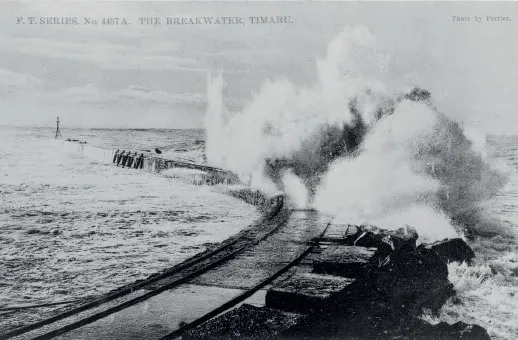

The breakwater, Timaru, c. 1910–13, photograph taken by William Ferrier.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, PA5-024

Colin may not have remembered his grandfather – he died at sixty-seven (the same age that Colin died) in 1922 – but he certainly ‘met’ him, since his photograph as an infant was taken by William Ferrier; throughout his life he took a lively interest in his grandfather’s work, acquiring copies of various published portfolios of photographs of Timaru and Mount Cook and environs, and often mentioning in letters details he came across about his grandfather’s career.6

School days in Dunedin and Ōamaru

After Colin’s birth, Ethel and John McCahon returned to Dunedin where they lived first at 288 Highgate,7 a long street on the western hills above North Dunedin, and later – after they returned from a temporary move to Ōamaru in 1930–31 – at 24 Prestwick Street, Maori Hill, less than 2 kilometres away. Colin attended Maori Hill School from the ages of five to ten (1924–29).

Crowd on the beach at Caroline Bay, Timaru, c. 1890, photograph taken by William Ferrier.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, PAColl-4746-02

McCahon gave revealing insights into his early schooling in a 1981 essay recalling three teachers who taught him in standards one, two and three at Maori Hill School. Their relevance to his future justifies fairly extensive quotation. In the infant classes Colin suffered an early experience of rejection for not conforming as expected, being left-handed: ‘I was a left-hander who couldn’t write as the teacher required. I had been battered to utter misery and exhaustion, bashed with straps, held hostage in front of the class, or made to stand up for ridicule on the desk top.’

Somehow I had moved on to standard one, where a lady floated like a waterlily into the room and into my life. She was as lovely as she looked. She came, I think, from Lumsden, and was named Miss Loudon. She worked hard, and got me going. I fell in love and, for my loved one, worked well. I was happy at last and thankful for her care and attention.

A pattern of rejection and acceptance would be recurrent in his life as a painter.

Then Miss Wishart … [C]oming back to school at the beginning of February, I met a very ‘with it’ lady, standing beside a large black cat and witch’s cauldron bubbling over an open fire – on the blackboard … She had short hair (dyed red?) and was reputed to have come from the art school in Christchurch!

The cat was her mind opener and then, BANG into lively arithmetic! All talked and then worked and BANG into story and poetry! Tennyson, Wordsworth, struggling with the moderns, and wonderful exercises in formal English spelling. You never knew what was happening to you. Poetry – words – words and pictures – and music – and grabbing it all. A year of joy, and at the end of this happiness, the awful threat of ‘Miss Guy’ the ogre of Maori Hill School – and me moving on there next year.

… She was a tough lady and a relentless teacher … Her real subject, as I look back, was ‘order’ – the order of thinking, looking and living. The glamour was over and, with it, the horror of the infant school … But now came the relentless Miss Guy who taught me to understand that the only way to put all the information I had together was by my own hard work.

Miss Guy was my most real angel.

The following year we moved to Oamaru and I went to Waitaki Boys’ Junior High, and cleaned up the standard five prize list – for Miss Loudon, Miss Wishart and Miss Guy.8

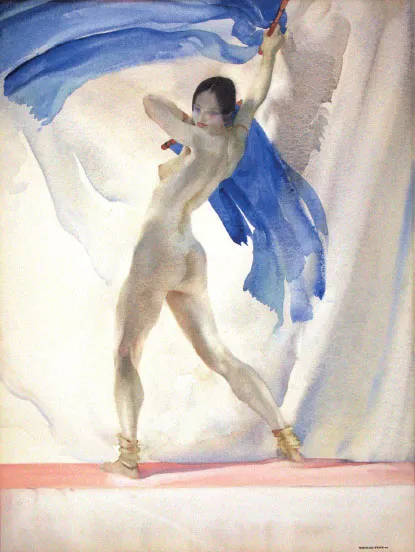

Russell Flint, The Banner Dance, c. 1928, watercolour, 670 x 502 mm.

Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 14-1928, bequeathed 1928 by Mr J. C. Marshall

Betty Wishart (1909–1990) was also an artist and occasional broadcaster. Several of these details point distinctly towards McCahon’s future. Arithmetic (numbers) and ‘Poetry – words – words and pictures – music’ – were all increasingly vital to his artistic project. Years later he told Patricia France: ‘Poetry, before painting, is my friend. The one without the other can’t exist.’9 He continued quoting poetry (including Tennyson), and using it in his paintings, all his life.10 Also, there is the emphasis on hard work and ‘the order of thinking, looking and living’; again, all central to his mature aesthetic and practice. For example, he once told poet and editor Charles Brasch (1909–1973): ‘This is where I am trying to go. Away from hysteria into order & value & reality. The other is so half way. Bach rather than Beethoven. Cézanne than Van Gogh.’11

McCahon’s early interest in art was stimulated by regularly attending exhibitions of the Otago Art Society (OAS), of which his parents were members, and at Dunedin Public Art Gallery (DPAG). He wrote in ‘Beginnings’:

We were a gallery-going family and went to all the exhibitions. At this time the big artistic event of the Dunedin year was the large Otago Art Society exhibition held in the Early Settlers’ Hall. When you are young and in love with paint...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Southern Beginnings, 1919–36

- 2 Dunedin, Nelson, Wellington, 1937–46

- 3 Tāhunanui, 1946–48

- 4 Christchurch I, 1948–49

- 5 Christchurch II, 1950–53

- 6 Titirangi I, 1953–58

- 7 Titirangi II, 1958–59

- Conclusion

- List of Artworks

- Exhibition Record, 1940–59

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright