eBook - ePub

Heroine

About this book

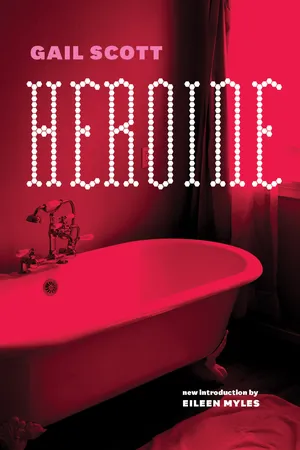

In a bathtub in a rooming house in Montreal in 1980, a woman tries to imagine a new life for herself: a life after a passionate affair with a man while falling for a woman, a life that makes sense after her deep involvement in far left politics during the turbulent seventies of Quebec, a life whose form she knows can only be grasped as she speaks it. A new, revised edition of a seminal work of edgy, experimental feminism. With a foreword by Eileen Myles.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

BEGINNING

Sepia

Sir. You can on-ly put ca-na-dien monee in that machine. No sir. No foreign objects nor foreign monee in that macheen. It’s an infraction, you see. The guard’s finger runs tight under the small print. The wooden squirrels in the rafters are si-lent. The Black tourist descends the steps with an astonished stare toward the telescope aimed at the city skyscrapers.

I’m lying with my legs up. Oh, dream only a woman’s mouth could do it as well as you. Your warm faucet’s letting the white froth fall over the small point on the tub floor. Your single eye watches my floating smiling face in its enamel embrace. Outside the shops swing. The wind has turned the trees to yellow teeth. This is the city. Montréal, P.Q. I work here. I’m a c—

That is I worked here ’til one day. I was sitting in that Cracow Café on The Main with its windows and walls sweating grey against the winter. Eating steamies made from real Polish sausage. Suddenly I looked up and there was this funny picture. A cross stuck in a bleeding loaf of bread. You were sitting under it smiling at me through your round glasses. Sort of, with your wonderful mouth, so feminine for a man’s. And your beat-up leather jacket.

Some hookers were standing round drinking hot chocolate. One was so wired up she kept doing a high step still holding her cup. Right leg over left leg. Twice. Left leg over right. There was no point trying to stop her. Somehow you managed to slide out over the torn red plastic seat and sit down beside me. Without anybody seeming to mind. I loved the smell of your cracked leather jacket. From Europe with love.

No, I’m telling stories. Maybe these women were your socialist revolutionary comrades trying to get stopped for soliciting so they could expose the brutality of the city administration. Some of them had middle-class skin.

I mean solidarity. If anyone asks, instinctively I have the answer. Loving women. In my case two. That is, the same set of brown eyes twice. We’re side by side on her bed. Then I’m lying on top of her soft breasts. She pulls up her white nightshirt and pulls down her panties so our genitals will touch. I – I think I rolled off. Yes it was me who stopped. Knowing I’m a failure. No. Never admit. Never admit you’re a failure.

The smell of coffee. Real cappuccino. A few leaves rush by a real prostitute bending her knees ’til her pussy comes forward. Then putting her hand on it. The harsh note is in the next booth saying: ‘She should adopt a more self-critical voice.’ His woman companion nods but her answer’s drowned in the noise. ‘You have a relationship,’ the guy is saying, ‘and you learn something from it. Next time you select better, that’s all.’ He shrugs. We get up to go. I like how your glasses hang on a string. When you’re not wearing them. Later, looking at the photos, I notice we’ve seen it all the same. The pretty prostitute, her jeans just right snugly over the V-shape but not too tight – Um, your hands reassure me. Confidently clicking the camera. Together we’re crossing the bar of light.

Colder times are coming. The Black tourist sees the plain whiten beneath the skyscrapers. The scene shifts to that dome-shaped café full of hippies and women in cloche-shaped hats. The sign says BAUHAUS BRASSERIE. It only fills half the lens. Jane Fonda goes by on a horse spattered with the blood of Vietnam. A gay man is fingering my homemade leather blouse and saying: ‘Sweetheart, you look so much like Barbarella.’ The new man and I get up to go. As we step out into the snow a woman comrade cries: ‘How come you never kiss anyone but her anymore?’ I’m a bit scared. We’re standing in the harbour. The gulls clack in the fog over the old schooner. I can’t hear my breath. Maybe we’re coming in unison. The illusion of perfect fusion. ‘Gail’s friends are my friends,’ you say in a soft voice. I’m so relieved. It’s starting to snow. Of course I didn’t know what you mean when you say that. Until I looked back and saw her head on your shoulder. Across the room at Ingmar’s when the sun shining through the lead glass delineated that dark place under your chin where it felt so safe. I’d been running from chair to chair on those Marienbad squares asking: ‘Have you seen Jon?’ as if I didn’t care. Suddenly she’s standing in front of me saying: ‘Why don’t you just relax?’

She’s right, Sepia. What I learned from her is that the relaxed woman gets the man. That was in the summer of ’76. When the RCMP hinted our group should leave the city if we didn’t want any trouble. The whole Montréal left was on the train. We called it our Olympic Vacation. Going to visit the other so-called Founding Nation. On that trip you’re in the woods for a good two days. Deep in reserve country with the trees leaning recklessly over the horizon. My legs were so anxious I wanted to jump off. Because I couldn’t forget the restaurant scene where someone said at the next table: ‘Elle a perdu; qui perd, gagne.’ I wrote faster. So fast and so small you could hardly see my handwriting. The cop at the counter watched as if I were writing in code. His handcuffs were at his belt. The gulls flew over the glassed-in roof. You used to sit there and think of sound, of the ships battering up and down between the waves. (I loved your mouth; it held me to you when the rest of your body cut like a knife.) You said: ‘I want to be free. No monogamy. It’s not for me.’ I laughed and pulled out my plum lipstick. ‘Tea for two,’ I said. ‘Decadence for me and decadence for you.’ No wonder you looked surprised. It wasn’t the right reaction.

Anyway, we were on the train. When suddenly I was awakened by an angel in a turquoise blazer. She held a CN card in her hand that said: WHILE ON THIS TRAIN YOUR WISH IS MY COMMAND. We watched her disappear in the night. Noting we’d forgotten to say the heat was pouring out from under the seat. Though it was the middle of summer. We never saw her again.

But I couldn’t get back to sleep. I was so worried about not being able to smile when the girl with the green eyes put her hand on your thigh.

A feminist (I kept repeating)

cannot be impaled

by a white prince.

The trip was like a dark tunnel. At the other end there would be light. When I got to Vancouver, I’d see, maybe, how to be free. Janis Joplin came on the radio. Her voice cracked like one of those evergreens trying to grow on the burnt earth outside Sudbury. She said: There’s no tomorrow, baby (laughing her head off). It’s all the same goddamned day. We learned that coming here on the train.

The Dream Layer

’Tis October. On the radio they’re saying ten years ago this month Québécois terrorists kidnapped the British Trade Commissioner. I was at my kitchen table. Through my window the mellow smell of autumn leaves in the alley. Making me slightly ill due to a temporary pregnancy. A drunk wove along the gravel. I was just wondering how to put it in a novel when the CBC announcer said: ‘We interrupt this program to say the FLQ has kidnapped Britain’s trade representative to Canada.’ I couldn’t help smiling. Even a WASP, if politicized, can recognize a colonizer. Besides, the crisp autumn air always made me restless. Later, my love, we laughed so hard when the tourist agent told the group from Toronto looking for cultural manifestations in Montréal: ‘Eh bien ici les manifestations ont lieu d’habitude au mois d’octobre.’ Winking at us in line behind them (we were going to Morocco). For in French manifestation also means political demonstration. He meant the October Crisis and other assorted autumn riots. People were freer then.

Alors pourquoi Marie a-t-elle dit que je ne serai pas au rendezvous? She meant on the barricades of the national struggle. Her face had this funny look, half guilty, half cruel. (She was still in the revolutionary organization then.) Even hinting that my grandfather might be Métis didn’t convince her. Of course I didn’t tell her and the other comrades the family kept it hidden. Why should I? They must have guessed anyway, because M, one of the leaders, tugged his beard and said: ‘We’re materialists. We believe one is a social product, marked by the conditions he grew up in. You’re English regardless of your blood.’ We were sitting in the revolutionary local. Around the table no one said a word. Even you, my love, I guess you wanted to keep out of it.

Marie’s face had that funny look again today when she came to visit. She was wearing an immaculate silk scarf. Over it her nose turned aside as if offended when she saw the state of my little bed-sitter. Granted, it’s kind of tacky. Green patterned linoleum and an old sofa. In the bathroom, black-and-white tiles like they have in the Colonial Steam Baths. Except some are falling off. Trying to make light of it, I said as we stepped into the room: ‘Ha ha, the hard knocks of realism.’ She didn’t laugh. She didn’t even smile ironically. So I decided to hold back. Refusing to explain how I’m using this place for an experiment of living in the present. Existing on the minimum, the better to savour every minute. For the sake of art. Soon I’ll write a novel. But first I have to figure out Janis’s saying There’s no tomorrow, it’s all the same goddamned day. It reminds me of those two guys I once overheard in a bar-salon: ‘Hey,’ said one, except in French. ‘Did you know the mayor’s dead?’ His lip twitched. ‘No kidding,’ said the other. ‘When?’ ‘Tomorrow, I think.’ They both laughed. Sure enough the next day on the radio they said the mayor was at death’s door. Nobody knew why. City Hall was mum. Rumour had it there’d been an assassination attempt by some unnamed assailant. I felt like I’d seen a ghost.

I got that same feeling again later taking a taxi along Esplanade-sur-le-parc. On my knee was the black book. The budding trees were whispering, the birds were singing: a beautiful spring eve. (Like when we first fell in love, my love.) When suddenly on the sidewalk I see a projection of my worst dreams. A real hologram. You and the green-eyed girl. Right away I notice she’s traded in her revolutionary jeans for a long flowing skirt. And her hair is streaked. Very feminine. As for you, you’re walking sideways, the better to drink her in. With your eyes. Oh God, obviously you can’t get enough. The taxi dropped me at the bar with the little cupid holding grapes in front of the mirror where I was going to meet some gay writers. One of them said: ‘Chérie, you look terrible.’ I was speechless. All I could think was what a coincidence. Because at the moment I saw you, my love, I’d been writing in the black book (not believing yet that our reconciliation was really finished): He’s Mr. Sweet these days. I’m the one who’s fucking up, making scenes. Oh well, tomorrow’s another day.

‘Qu’as-tu?’ asked Alain. He has green eyes like my father, but he wears jewellery.

I said: ‘I think I’ve seen a ghost. Real-life from a nightmare I once had. Everything back exactly as it was.’

‘Trésor,’ dit-il, ‘la science dit que la répétition n’existe pas. Les choses changent imperceptiblement de fois en fois. Maintenant tu vas prendre un bon verre.’ I didn’t reply, concentrating as I was on how to be a modern woman living in the present while at the same time finding out who lied, my love, me or you?

A delicious warm sweat is forming on the bathroom tiles. Through the open door I see the dented sofa where Marie sat this afternoon. Determined as ever with her flat stomach and her straight back. In that immaculate white silk. Suddenly she put her hand over her mouth, as titillated as a little girl who’s caught a glimpse of something unspeakable. I knew it was that place above the stove where the dirt adheres to the grease, working the paint loose until it starts to peel off. And she was about to criticize my housecleaning. To ward it off I focused on how growing up over that dépanneur in St-Henri probably made her fussy. Every Monday and Thursday after school she had to take off her blue tunic and scrub and scrub the slanting floor under the domed roof. What got her was the darkness of the courtyard. You could feel it from the kitchen window. One day, walking in there she found a big rat lounging on the table. Slowly unwinding his virile tail, he looked at the little girl with his small eyes and said: ‘Mademoiselle, voulez-vous me ficher la paix?’ In International French. She couldn’t think of a thing to say. None of the neighbours spoke like that. Later, she thought it was a dream.

Glancing only slightly in my direction, she blurted it out in spite of herself: ‘Tu pourrais faire un peu de ménage. On dirait que tu n’as plus d’amour-propre.’

I kept silent. It’s better than saying: ‘What about you? You’re too obsessed with how things look.’ Besides, as I’d decided to take a bath, I was busy with my ablutions.

I guess I lost track of time. Because I didn’t see her get up and say goodbye. I realized she hadn’t said anything about coming back.

Colder times are coming. In the telescope the plain whitens. The tourist sees a field of car wrecks below the skyscrapers. A woman is walking toward a park bench. Suddenly she sits, pulling her coat down in the front and up in the back in a single gesture so you can hardly tell she’s taking a pee.

Oh, faucet, your warm stream is linked to my smiling face. Outside the shops swing: peanuts, blintzes, Persian rugs. Marie m’a dit: ‘Tu as payé avec ton corps.’ Shhh. Reminiscences are dangerous. Who said that? Never mind. When I get out of here I’m going to throw out those old pictures on the stool by the tub. That one half-hidden in the folds of the second-hand lime-green satin nightgown must have been taken in Ingmar’s courtyard. Black and white with a silvery grey light shining on the shoulders of our dark leather jackets. We were the perfect revolutionary couple, tough yet happy. Leaning together after a walk in the Baltic fog, eating almond-cream buns. Except at Ingmar’s somebody almost stole the silver plate from me.

What went wrong wasn’t obvious. Earlier, travelling in Morocco, everything seemed perfect. The magic was in slipping out of time. No landlords, no waiting for you to phone, my love. The air was filled with spice, roast lamb, mysterious music, the delicate odour of pigeon pie. From our hotel room we heard an Arab kid with a knife offer to make a rich woman tourist high for a price. We laughed as his voice mocked her under the arch of the starry sky (’twas in life before feminism). I loved our mornings. Honey and the smell of Turkish coffee in the huge café at Poco Socco. With the passing donkeys and men in felt hats and beautiful djellabas obscuring our view of the rich American junkies on the other side, I wrote a poem:

the music of your tongue

slides between my lips

the tongue of your sandal

between my toes

glides through the grass in the orange grove

there has been a communist purge

a dead scorpion lies upturned

on the road to the fortress

Then we were heading northeast across the desert. After a day and a half, the train rolled into flowered vineyards, then the city of Algiers. In a lighted square, a white-clothed man with a thin dog leaned back, playing his flute to lions of stone. Stepping off the train, a plainclothes cop arrested us. It was midnight. He led us out under the Arabian arches of the station. Saying it was for our own protection. Because the streets at night are dangerous. ‘God,’ I thought, ‘somehow they’re on to the fact we’re into heavy politics back in Montréal. What if they find the poem with the word ‘communist’ in my purse? Now I’ve really blown it.’

The police station was plastered with pictures of missing children. Beautiful girls and boys of all ages. Probably sold to prostitution. That’s racist. They let us spread our sleeping bags in the same cell. When in the morning they said: ‘You can go now,’ my love, I was so relieved it seemed that anything was possible. So at a fish supper in a fort restaurant on the middle corniche where Algerian freedom fighters had daringly resisted the French, I said: ‘You’re right to be against monogamy. As long as we trust each other anything’s okay.’ Through the open window I saw a beautiful brown man, naked from the chest up. He was looking in, holding a fish net. As if he’d emerged from the sea. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘the couple is death for women.’ You smiled with your wonderful soft lips. We headed north. In the mirror of a hotel room in Hamburg, you took a self-portrait.

Everything was perfect.

Except, at Ingmar’s, your mother’s boyfriend’s winter house on the Baltic, something started going wrong. That particular morning, I must have been dreaming. Because lying back I saw a face looking through a window, smiling. Vines around its neck. Glistening as though it had risen from the sea. Only, outside a slow brown river ran. It was the city. Pink lights on tall white buildings. Red and yellow streets. I woke up to a winter morning. Shadows of noir et blanc. Smell of coffee in a china cup. Bluish tile cooker reaching to the ceiling, Northern European style. Yes, everything was perfect. So why at that precise moment did I get up, open the cooker’s little brass door, and throw the photos of your former lovers in the fire? Just as you came in.

Your silence left me confused. All that European retinue across the winter room. Then the Modigliani print on the wall behind the golden strands of your hair reminded me I needed a man like you to learn of politics and culture. I’d have to try harder. Thank God, despite my error, our days continued to be wonderful. Walking white streets eating almond-cream buns. The falling snow giving an air of harmony. Yet under that blanket of perfection (we were a beautiful couple, everybody said so) the warmth seemed threatened. As if I couldn’t handle the happiness. Secretly the darkness of the closet beckoned. I wanted to sink down among the silence of your coats. (Good wool lasts forever.) Your mother, turning her head from a conversation with her son, said to me: ‘À quoi ressemble ta famille?’ I saw the smokestacks of Sudbury. And her emaciated face sitting on the veranda. ‘Fine,’ I answered, smiling broadly as if I didn’t understand the question.

The feminist nemesis was that the more I felt your love the harder it was to breathe. In Hamburg, when the subway stopped between two stations and the lights went out, I began to sweat. Pins and needles pricked my chest so much I wanted to grab your sleeve and say: ‘Help, please.’ But hysteria is not suitable in a revolutionary woman. Thank God a winter-shocked unemployed Syrian immigrant started to bark. His family gathered round him laughing nervously. Eyeing back the fishy stares of other passengers as if it were a joke. As if it were a joke. My fear of crowds at demonstrations was harder to conceal. Although you’d have been initially forgiving. Because paranoia in new politicos is normal. Given how scary it is to become conscious of the way the system really works. Anyway, following that little blow-up at Gdansk, when we went to a local march in solidarity, I heard the press of soldiers’ feet beh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Part I: Beginning

- Part II

- Part III: Ending

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Heroine by Gail Scott,Gail Scott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.