- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Book of a Thousand and One Nights, better known as The Arabian Nights, is a classic of world literature and the most universally known work of Arabic narrative. Although much has been written about it, Professor Ghazoul's analysis is the first to apply modern critical methodology to the study of this intricate and much-admired literary masterpiece.

The author draws on a wealth of critical tools -- medieval Arabic aesthetics and poetics, mythology and folklore, allegory and comedy, postmodern literary criticism, and formal and structural analysis -- to explain the specific genius of the The Arabian Nights. The author describes and examines the internal cohesion of the book, establishing its morphology and revealing the dialectics of the frame-story and enframed cycles of narrative. She discusses various forms of narrative -- folk epics, animal fables, Sindbad voyages, and demon stories -- and analyzes them in relation to narrative works from India, Europe, and the Americas. Covering an impressive range of writings, from ancient Indian classics to the works of Shakespeare and the modern writers Jorge Luis Borges and John Barth, she places The Arabian Nights in the context of an ongoing storytelling tradition and reveals its influence on world literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nocturnal Poetics by Ferial J. Ghazoul in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Web Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

TEXTUAL VARIANTS AND CRITICAL METHODOLOGY

Text(s)

Free Text

Choosing any text for critical study invites the question of why the particular given work has been selected. With The Arabian Nights, this question becomes more complex, since the why is accompanied by the which as The Arabian Nights itself is a multiplicity of texts. Thus, an important first question is: Which Arabian Nights, and what version of it?

The textual history of The Arabian Nights is intricate and the major problems of origin and genesis remain unresolved. Our knowledge of The Arabian Nights stems from its numerous extant variants, and from the cursory references of Arab historians to the text.

The earliest extant fragment of The Arabian Nights dates from the ninth century. But to refer to it as a fragment of The Arabian Nights is somewhat misleading, for it is nothing more than the title page and a badly preserved first page. The manuscript is probably of Syrian origin. Its exact title is Kitab hadith alf layla (“Book of the Discourse of the Thousand Nights”) and on the first page figures a Dinazad who asks Shirazad to relate her promised tales.1 This much hardly allows us to conclude that this ninth-century text is identical to the version we know.

The earliest references to The Arabian Nights are to be found in the works of tenth-century historians. The following passage from Mas‘udi in his Golden Meadows deals briefly with The Arabian Nights:

The case with them (viz., some legendary stories) is similar to that of the books that have come to us from the Persian, Indian (one MS has here Pahlawi) and the Greek and have been translated for us, and that originated in the way that we have described, such as, for example the book H azar Afsana, which in Arabic means ‘thousand tales,’ for ‘tale’ is in Persian afsana. The people call this book ‘Thousand Nights’ (two MSS have here ‘Thousand Nights and One Night’). This is the story of the king and the vizier and his daughter and her servant girl; these two are called Shirazad and Dinazad (in other MSS: ‘and her nurse’; in again other MSS: ‘and his two daughters’).2

In al-Fihrist, written in 987 a.d., Ibn al-Nadim mentions Hazar Afsan and sums up the plot of the frame story.3 However, the Persian origin of The Arabian Nights has been disputed by well-known Orientalists. Antoine Silvestre de Sacy (1758–1838) wrote extensively on the subject, putting forward the thesis that The Arabian Nights was written at a later period and without the use of Persian and Indian sources. He casts doubt on the authenticity of Mas‘udi’s well-known passage.4 There are other sporadic references to The Arabian Nights, notably by the Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi (1346–1442), but they shed little light on the origin or the evolution of the text.

The oldest surviving version of The Arabian Nights is the four-volume manuscript sent to the first translator of The Arabian Nights, Antoine Galland (1646–1715). His translation in the early eighteenth century was only partly dependent on this manuscript. He used other unidentified manuscripts as well as oral transmission by a man from Aleppo. The last volume of Galland’s manuscript is lost but the first three are in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. This manuscript probably dates from the fourteenth century.

Manuscripts of The Arabian Nights are in libraries of major European capitals and in Cairo; their texts vary and overlap. However, there is no “complete” edition of a variant. D. B. MacDonald worked on editing the manuscript of Galland but did not finish this laborious project. Muhsin Mahdi has edited and introduced the earliest Arabic variant, based on extant manuscripts, but it stops at the 152nd night.5

Comparative study of these different versions and the use of internal evidence demonstrated beyond any doubt that there is no single extant text from which other variants issued—a multiplicity of texts constitute the points of departure.6 The process of creation in The Arabian Nights, as in oral literature, is based on crystallization. There is neither an original text nor an individual author. The Arabian Nights is an artistic production of the collective mind; its specificity lies in its very emergence as a text. The typical text is often conceived as a limited and defined object—as a singular event. In contrast, The Arabian Nights is plural and mercurial, and herein lies its challenge. How to accommodate and grasp the complexities of this ambiguous literary phenomenon without reducing it and judging it by standards of written literature is the task I have undertaken in this study. However, the dividing line should not be between written or oral literature, for there is oral literature which has maintained the textual wording without the slightest modification, in most such cases because of its association with divine revelation or revered wisdom. Sacred texts, even when oral, tend to survive intact. So do proverbs and poems, which are generally well preserved. The real dichotomy should be between the fixed and the free text. In the fixed text the words are part of the narrative and the oral recitation resembles the written text in its adherence to wording. In free texts the lexical element varies but structural logic and thematic content remain the same. The comparison of free texts is based on the plot, characters, and setting.7

The various available versions of The Arabian Nights cannot be thought of in any hierarchical terms. There is no parent textual variant that proliferated into others, at least not that we can identify and reconstruct with any assurance. The Arabian Nights probably grew into what we know it to be over centuries of deposited layers of narratives. Comparison of various manuscripts reveals a similar framework story, but there are considerable variations in the nature, number, and order of enframed stories. The published “complete” editions of The Arabian Nights are either modifications of one manuscript, as in the first Cairo edition, commonly known as the Bulaq edition (1835), or rearrangement of a number of manuscripts, as in the second Calcutta edition (1839–1842). The translations follow the same course—they either stick faithfully to one Arabic text, as in Francesco Gabrieli’s Italian translation, or translate a combination of Arabian Nights texts, as Edward Lane did.8

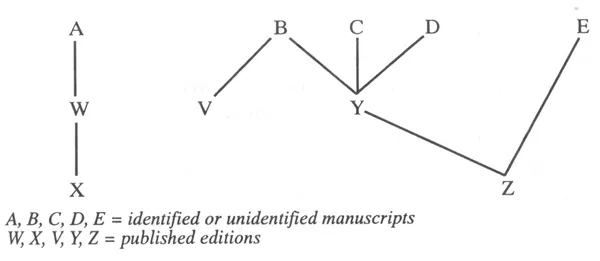

A diagram of the historical evolution of a “complete” text of The Arabian Nights from manuscript to printed form can be represented as follows:

It is impossible to reconstruct an accurate chart of relationships for all published editions, since some of the manuscripts which were the basis for these editions are lost.9 However, it is important to understand that the variation in texts is not an accident due to inadequate transmission, but is rather a fundamental aspect of the narrative performance of The Arabian Nights and an intimate characteristic of the received texts.

Flexible Narrative

The phenomenon of a free text is not uncommon in oral tradition, but The Arabian Nights is not simply a manipulable substance that can be reworked and rephrased to adjust to new social and economic conditions, as can myths of preliterate peoples.10 It seems that it was constructed in such a way as to allow and even invite radical changes in its content, yet at the same time preserve its own internal logic. The Arabian Nights is constructed like a game of skill (as opposed to a game of chance) such as chess. There are indefinite ways of playing the game, but it remains—despite its many variations—a chess game. Similarly, the text preserves its identity although it is performed, as it were, in more than one way.

The flexibility of the narrative is guaranteed by an enclosing structure which can contain a multiplicity of genres, conflicting styles, and divergent themes without destroying in the least the coherence of the text. We can attest to this empirically: the two French translations of Galland and Mardrus play havoc with the “original” Arabic text, and yet The Arabian Nights is not compromised by such “unfaithfulness.” Edward Lane, the English translator, used the cut-and-paste technique rather freely, deciding to cut out whole sections and rearrange others. Adding, dropping, and reshuffling stories seems to be a temptation to any transmitter of The Arabian Nights. A number of writers indulged in writing sequels to The Arabian Nights, notably Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote a sardonic tale of the one thousand and second night. If the text has been handled frequently in this promiscuous fashion, it is indicative that the text allows itself to be “mishandled.” One cannot blame a Lane or a Galland for taking liberties with the text; after all, texts get the treatment they deserve. It is true that Littmann’s German translation, Haddawy’s English translation, and Khawam’s French translation have been praised for their consistency and accuracy, and have been considered “reliable” in relation to their Arabic source. But the fact remains that there are many editors and translators who have been tempted to revise the text. This cannot be easily dismissed—something in the text makes it subject to manipulation. It is constructed so as to accommodate and incorporate different material, as in an anthology or a compendium.

Though the versions and adaptations of The Arabian Nights vary considerably, certain structural characteristics remain constant, namely a fairly stable enclosing story and a relatively unstable enclosed content. To establish a supreme invariant would require a delineation of the regularly occurring elements. The elements that are repeated in all variants are not necessarily worded or expressed in the same manner—they are simply the elements that share the same function in the narrative progression. For example, in the framework story there is a famous scene where the king’s wife is found copulating with a black slave. This incident has been rendered in variety of ways by different publishers and translators. A Jesuit priest retold it in the following way:

There were some windows facing his brother’s palace, and while he was looking out, the palace door opened and out came twenty slave-girls and twenty black male slaves. His sister-in-law, who was exceptionally beautiful and lovely, was walking along with them until they came to a fountain and all sat at its side. Then they began to drink, play, sing, and recite poetry until close of the day.11

On the other hand, the well-known French translation made by Antoine Galland lingers over this incident:

Une porte secrète du palais du sultan s’ouvrit tout à coup, et il en sortit vingt femmes, au milieu desquelles marchait la sultane, d’un air qui la faisait aisément distinguer. Cette princesse, croyant que le roi de la Grand-Tartarie était aussi à la chasse, s’avança avec fermeté jusque sous les fenêtres de l’appartement de ce prince, qui, voulant par curiosité les observer, se plaçe de manière qu’il pouvait tout voir sans être vu. Il remarqua que les personnes qui accompagnaient la sultane, pour bannir toute contrainte, se découvrirent le visage, qu’elles avaient eu couvert jusqu’alors, et quittèrent de longs habits qu’elles portaient pardessus d’autres plus courts. Mais il fut dans un extrême étonnement de voir que dans cette compagnie qui lui avait semblé toute composée de femmes, il y avait dix noirs, qui prirent chacun leur maîtresse. La sultane, de son côté, ne demeura pas longtemps sans amant; elle frappa des mains en criant: Masoud! Masoud! et aussitôt un autre noir descendit du haut d’un arbre, et courut à elle avec beaucoup d’empressement.

Les plaisirs de cette troupe amoureuse durèrent jusqu’à minuit. Ils se baignèrent tous ensemble dans une grande pièce d’eau, qui faisait un des plus beaux ornements du jardin; après quoi, ayant repris leurs habits, ils rentrèrent par la porte secrète dans le palais du sultan, et Masoud, qui était venu de dehors par dessus la muraille du jardin, s’en retourna par le même endroit.12

A Western children’s version of the tale relates the incident in a radically different way:

He had a wife whom he loved dearly and many slaves to carry out his smallest wish. He should have been one of the happiest men in the world.

And so he was, until one day he found his wife plotting against him. He had her put to death at once, but still his rage was not satisfied.13

The most popular and one of the oldest printed Arabic editions relates the incident with a certain immediacy:

Now there were some windows in the king’s palace commanding a view of his garden; and while his brother was looking out from one of these, a door of the palace was opened, and there came forth from it twenty females and twenty male black slaves, and the king’s wife, who was distinguished by extraordinary beauty and elegance, accompanied them to a fountain, where they all disrobed themselves and sat down together. The king’s wife then called out, O Mes‘ood! and immediately a black slave came to her, and embraced her; she doing the like [and he copulated with her]. So also did the other slaves and the women; and all of them continued reveling [kissing, hugging, fucking, and so on] until the close of the day.14

In the most recent English translation of the earliest extant version, this episode is rendered like this:

The private gate of his brother’s palace opened, and there emerged, strutting like a dark-eyed deer, the lady, his brother’s wife, with twenty slave-girls, ten white and ten black. While Shahzaman looked at them, without being seen, they continued to walk until they stopped below his window, without looking in his direction, thinking that he had gone to the hunt with his brother. Then they sat down, took off their clothes, and suddenly there were ten slave-girls and ten black slaves dressed in the same clothes as the girls. Then the ten black slaves mounted the ten girls, while the lady called, “Mas‘ud, Mas‘ud!” and a black slave jumped from the tree to the ground, rushed to her, and, raising her legs, went between her thighs and made love to her. Mus‘ud topped the lady, while the ten slaves topped the ten girls, and they carried on till noon.15

These five versions of this crucial incident—despite their outward differences and thematic variations—share a common trait and play the same role in the unfolding of the narrative. Whether an expurgated Jesuit variant or an obscene Cairene version, the function of the incident in the macro-context of the plot remains constant. It is the committing of a forbidden act. The offense is no ordinary one, for the king’s wife not only transgressed marital boundaries but class and ethnic ones as well. The offense approximates a violation of taboo. The na...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II

- Notes

- Bibliography