eBook - ePub

Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East

Case Studies from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East

Case Studies from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey

About this book

Irregular or illegal housing constitutes the ordinary condition of popular urban housing in the Middle East. Considering the conditions of daily practices related to land and tenure mobilization and of housing, neighborhood shaping, transactions, and conflict resolution, this book offers a new reading of government action in the cities of Amman, Beirut, Damascus, Istanbul, and Cairo, focussing on the participation of ordinary citizens and their interactions with state apparatus specifically located within the urban space. The book adopts a praxeological approach to law that describes how inhabitants define and exercise their legality in practice and daily routines. The ambition of the volume is to restore the continuum in the consolidation, building after building, of the popular neighborhoods of the cities under study, while demonstrating the closely-knit social relationships and other forms of community bonding.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East by Myriam Ababsa, Baudouin Dupret, Eric Dennis, Myriam Ababsa,Baudouin Dupret,Eric Dennis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Urbanisme et développement urbain. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mukhalafat in Damascus: The Form of an Informal Settlement

Mukhalafat in Damascus: The Form of an Informal Settlement

Etienne Léna

Ancient Informal Settlements

In 1936, in his preliminary report, René Danger, a land surveyor and town planner working on the Plan for Development, Extension, and Embellishment of the city of Damascus (Danger 1937),1 was already concerned by a phenomenon of illegal construction in the market gardens that surround the city and the risks this posed for city resources (Danger 1937). Danger, who had a legalistic vision of his role, proposed, on the basis of urban rules developed in the metropolis, the creation of a non-aedificandi zone for gardens. Several years later, in their report on a new town plan of Damascus, Ecochard and Banshoya only mentioned the informal housing environment in the zone plan key: a 500-meter-wide belt of gardens around the city had to be preserved in order to “stop illegal constructions” (Friès 2000).

These attempts to restrict construction in the ‘Ghouta’—as the oasis surrounding Damascus is called—had little effect. From 1984 to 1994, the population of Damascus grew by 67 percent, with 40 percent living in the informal settlements around the city, causing certain large areas of the Ghouta to disappear over a very short period of time (Balanche 2006).

Around the time Danger began to notice cheap constructions in the city gardens, Damascus had just expanded at its northern and southern districts, in places such as Amara, or the north of Midan.2 These lots were also built on market garden land on the edges of already urbanized districts, and were observed and described as “urban facts,” even if there is no trace of the transactions that led to them that could shed light on their legality or otherwise (Arnaud 2006).

Today, many buildings in the suburbs of Damascus are illegal and built quickly using poor-quality concrete blocks. Although these constructions recall those described by Danger, the scale and organization of the illegal districts (mukhalafat) bear a strong resemblance to the descriptions of lots found in the suburbs of Damascus that were urbanized in the mid-nineteenth century, suggesting that illegality notwithstanding, we are also facing a clear “urban fact” (Rossi 1990).

In planned urbanization, rules are pronounced in order to set guidelines for what should be regarded as conforming to the norm. Those rules give shape to the city through definitions of density, limits, surface areas, aspects of construction, functional allocation, and so on (Laisney 1988). The parameters to be taken into account in an ‘informal’ housing process do not follow promulgated rules but result from factors that are not legally formulated: the nature of the urbanized land, its structure before the construction of buildings (division of land, nature of subsoil, land pressure felt on the sector, nature of existing infrastructures), and the terms and methods of ‘acquiring’ the land. There are also rules and constraints that those who build the lots effectively impose on themselves: whether these are due to their financial means, or their respect for certain rules of behavior (Akbar 1988).

Mukhalafat of Daraya

After a brief survey of different areas around Damascus, for this study we chose a specific district north of the town of Daraya, which is about eight kilometers southwest of Damascus, along the road to Jerusalem (Fig. 1.1 and 1.2). The main reason for its transformation was not rural depopulation but rather the massive process of urban renewal a few kilometers north that led an already urbanized population to build in this area. The survey was carried out by a team of four Syrian architects and architectural students, together with a research fellow in sociology. As there was no prior authorization from the authorities for this research to be carried out, houses were only documented with the owners’ consent.

The result of this campaign was the registration of sixty-seven houses3 and five lots, surveyed in an area measuring 1,000 by 400 meters. Ten title deeds were photographed.4 Aerial photographs from 2006 and 2007 made available by GoogleEarth® and a page of the Daraya land registry of 1930 drawn by Camille Duraffour, allowed us to situate the houses in their surroundings.

Fig. 1.1: Location of Daraya, southwest of Damascus. Illustration by Etienne Léna, from Google Earth 2007.

Fig. 1.2: Location plan for surveyed plots in Daraya. Dark gray indicates plots surveyed. Illustration by Etienne Léna.

Although the results cannot lead to representative statistics, they give a very good picture of the diversity of building processes. A wide range of different kinds of buildings was visited, and the area studied showed different stages of development: from agricultural land still being cultivated, to single houses becoming complex buildings; from single units to the creation of a lot; from plans to houses under construction. Within that area we could observe all the stages of development of this area of the city.

Manufacturing Units: Concrete Blocks, Frames, and Houses

The characteristic feature of the informal districts of Damascus suburbs is the gray uniformity of the concrete block constructions. The blocks are produced in small factories like the one established in the sector we studied. Two workers run the factory with a small concrete press. The blocks are stored on the edge of a 620-m2 plot. One laborer mixes the concrete with a shovel and pours a mixture of sand, gravel, cement, and water into the press. It is then vibrated with an engine, and produces concrete blocks 40 cm long × 15 cm wide × 20 cm high. Average daily production is approximately three hundred concrete blocks. The second laborer organizes the blocks once they have been pressed: he lays them out on the ground so that the concrete sets uniformly, arranges them in a low wall ten courses high and 40 cm thick, maintaining spaces between the blocks to finish the setting, and finally stacks them packed together for sale. Each concrete block is sold for 15 Syrian Pounds (SYP).5

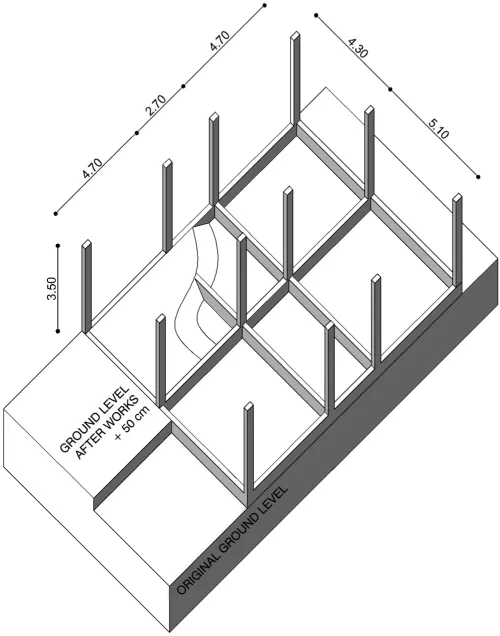

The main construction system used to build houses or buildings is based on a post-and-beam frame, filled with concrete blocks (Fig. 1.3). For it to be economical, this system must adapt to the surface area to be covered and the quantities of materials (steel frame and concrete) required. According to the laborers questioned on a house building-site, the most economical length is approximately 4.5 m for beams with a cross-section of 20 cm width × 25 cm height. The foundations form a network of beams 50 cm in height, cast directly on the ground, which leads to the progressive raising of the public road system. Posts with a cross-section of 20 cm × 40 cm are then erected at a level equivalent to fifteen to seventeen courses of blocks.

Fig. 1.3: The basic post-and-beam skeleton used for housing construction. Illustration by Etienne Léna.

Almost all houses and buildings are built following this system. For example, house 501, built on a plot measuring 11.20 m × 11.2 m, or 125.4 m2, with six rooms (a family living room, bedrooms, and guest sitting rooms), a kitchen, a bathroom, and a staircase to access the roof, required approximately 3,500 concrete blocks for its construction. According to the contractor building the house, the selling price of his labor is SYP4,500/ m2, 50 percent of which is allocated for a bribe with which to secure an administrative blind eye to a period of three days during which the house must be built. Because the owner of house 509 refused to pay his share, the construction was partially demolished three times by the municipal authorities.

The construction process is therefore very rapid and requires many laborers. After drawing out the limits of the plot, four or five carpenters build the formwork out of wooden board for foundations (Fig. 1.4). The iron framework is erected immediately afterward, on the same day. Then about twenty workers mix and pour the concrete into the foundations. It takes two days and about ten workers to cast the posts that support the first floor, to cast the floor itself, and fill the framework with concrete blocks.6 All openings are walled up immediately, and the front door is fitted to ensure the safety of the equipment that will be stored inside for the duration of the building work. The whole operation takes between three and five days. Props to support the upper floor are kept in place for a week for the concrete to set. The rest of the building is then completed, either by specialized professionals (carpenters, electricians, and plumbers), or by the future occupant. This second stage can take much longer, depending on the financial means of the future occupant.

Fig. 1.4: Carpenters building formwork out of wooden board for foundations. Photograph by Etienne Léna.

Two Dominant Models: Courtyard Houses and Villas

Although the structural system described above leads to homogeneous standards regarding the dimensions of each room, the survey revealed different types of buildings. Among the sixty-seven houses documented, there are three main types, two of which are dominant and can be linked to known models. Since the third type is mainly characterized by its compactness and a lack of outdoor space, designed to take full advantage of the lot’s assigned area, we will call it ‘speculative.’ Other buildings stem from the two main categories: farm houses, which are related to the courtyard type, and multistory building...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Illustrations

- Contributors

- Introduction: Forms and Norms: Questioning Illegal Urban Housing in the Middle East: Myriam Ababsa, Baudouin Dupret, and Eric Denis

- Part 1: The Production of Forms and Norms from Within: 1. Mukhalafat in Damascus: The Form of an Informal Settlement: Etienne Léna

- 2. Selling One’s Property in an Informal Settlement: A Praxeological Approach to a Syrian Case Study: Baudouin Dupret and Myriam Ferrier

- 3. Securing Property in Informal Neighborhoods in Damascus through Tax Payments: Myriam Ferrier

- 4. Inhabitants’ Daily Practices to Obtain Legal Status for Their Homes and Security of Tenure: Egypt: Marion Séjourné

- 5. Vertical versus Horizontal: Constraints of Modern Living Conditions in Informal Settlements and the Reality of Construction: Franziska Laue

- 6. The Politics of Sacred Space in Downtown Beirut (1853–2008): Ward Vloeberghs

- 7. Shared Social and Juridical Meanings as Observed in an Aleppo ‘Marginal’ Neighborhood: Zouhair Ghazzal

- Part 2: Public Policies toward Informal Settlements: From Eviction to Self-help Recognition (or Legitimization) and Back: 8. Secure Land Tenure? Stakes and Contradictions of Land Titling and Upgrading Policies in the Global Middle East and Egypt: Agnès Deboulet

- 9. The Commodification of the Ashwa’iyyat: Urban Land, Housing Market Unification, and de Soto’s Interventions in Egypt: Eric Denis

- 10. Public Policies toward Informal Settlements in Jordan (1965–2010): Myriam Ababsa

- 11. Mülk Allahindir (‘This House is God’s Property’): Legitimizing Land Ownership in the Suburbs of Istanbul: Jean-François Pérouse

- 12. Law, Rights, and Justice in Informal Settlements: The Crossed Frames of Reference of Town Planning in a Large Urban Development Project in Beirut: Valérie Clerc

- 13. The Coastal Settlements of Ouzaii and Jnah: Analysis of an Upgrading Project in Beirut: Falk Jähnigen