- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Akhenaten Colossi of Karnak

About this book

Some of the most fascinating sculptures to have survived from ancient Egypt are the colossal statues of Akhenaten, erected at the beginning of his reign in his new temple to the Aten at Karnak. Fragments of more than thirty statues are now known, showing the paradoxical features combining male and female, young and aged, characteristic of representations of this king. Did he look like this in real life? Or was his iconography skilfully devised to mirror his concept of his role in the universe? The author presents the history of the discovery of the statue fragments from 1925 to the present day; the profusion of opinions on the appearance of the king and his alleged medical conditions; and the various suggestions for an interpretation of the perplexing evidence. A complete catalog of all major fragments is included, as well as many pictures not previously published.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Akhenaten Colossi of Karnak by Lise Manniche in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Discovery

The first person in modern times to set eyes on the extraordinary sculptures of Akhenaten was Maurice Pillet, French architect and director of works for the Egyptian Antiquities Service at Karnak. On 1 July 1925 he was engaged in rescue work east of the eastern gate of the enclosure wall of the Karnak temple where an existing drain, dug alongside the wall on three sides, was being enlarged to protect the temple from damage caused by rising subsoil water. Pillet did not record the circumstances of his discovery, and his name is connected with it only through brief references by his successor, Henri Chevrier, a year later. Blocking the intended extension of the drainage canal Pillet had found the remains of

Fig. 1.1 East Karnak today with the eastern gate of Karnak and the temple behind.

Fig. 1.2 One of the first two colossi found in the drainage ditch: JE 49529 (A1).

- two very large colossi of Akhenaten (A1, D9) (“deux statues très importantes d’Akhnaton”)1

It is a curious fact that they were among the best preserved of all the colossi, most of the rest, found in rather more carefully planned excavations, being reduced to body parts. Without further ado the two colossi were dispatched to the Cairo Museum where they were cataloged as Journal d’Entrée 49528 and 49529. In an article written much later, in 1961,2 Pillet briefly discusses the appearance of the colossi and previous assessments of their qualities (see Chapter 3), but nothing is mentioned about the discovery of the first two.

Since it has not been possible to identify the majority of the body parts mentioned by Chevrier with specific sculpture and inventory numbers of museums and storerooms, it was considered appropriate to include reference to the numbers applied in our catalog section of body parts (Chapter 2) only where an identification is certain. Chevrier’s vague chronological numbering system from the time of his excavations has also been abandoned, the individual items as discovered being here indicated by an indented line and in bold letters.3

Chevrier was an engineer by profession, and took over from Pillet on 20 March 1926, the main tasks being the massive clearing and restoration work required in the temple of Amun. His specific duties for the remaining months of the season were to continue clearing the Third Pylon and removing the items found in it, and “to explore the part of the drain which gave us this summer the two statues of Akhenaten to see if there might be other statues or other fragments,” as well as to initiate the rebuilding of the temple of Khonsu, or that of Ramesses III, or the buildings of Hatshepsut near the sanctuary.4 On studying earlier photographs of the area showing crumbling pylons and collapsed columns, one realizes why such rescue work outside the temple proper may have been seen as an unwelcome distraction, and why Chevrier’s annual reports in the Annales du Service des Antiquités d’Égypte (ASAE) are reduced to the bare minimum—this in spite of the fact that he recognized the statues as being “very large” and “truly extraordinary.”5 The area east of the temple was a dump, filled with a layer of 1.5–2m of soil that had been dug from the canal and added to the accumulated residue of millennia when it had been used as a burial ground.6

It took the workers a week to reach the level of the statues, the first discoveries consisting of:

- fragments of cartouches with remains of blue pigment and parts of hands (“fragments de cartouches dont les creux portaient des traces bleues et fragments de mains”)7

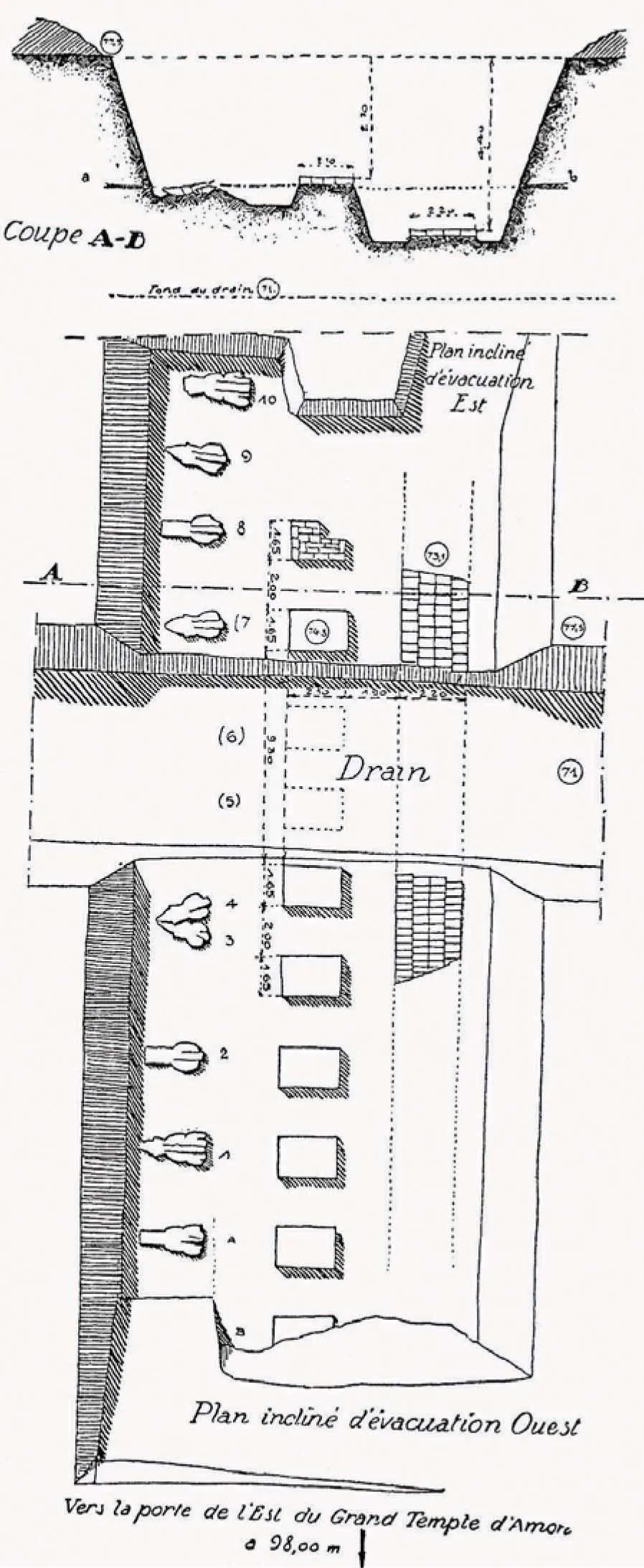

Three days later the lower course of a pillar appeared, set on a layer of chipped sandstone. Chevrier followed the east-west line suggested by the position of the first two colossi and pillar base, clearing the area toward the east wall of the temple as illustrated in his report (fig. 1.3).

What look like footprints in the plan represent a head with a crown and back pillar. According to Donald B. Redford, who was to continue the excavations at a much later date (see pages 14–16), this is an oversimplified plan.8 Letters A and B refer to fragments found the following season.9 Chevrier soon came across:

- nine heads (“la première des neuf têtes qui devaient être découvertes pendant la campagne”)10

bringing the total of known colossi to eleven. His figs. nos. 1–4 in the report give a selection of heads and crowns from these first two campaigns: presumably those later to become Cairo TR 29.5.49.1 (B4) and JE 98894 (D8), as well as JE 49528 (D9) and JE 49529 (A1). A numbering system then had to be devised for his report. On his first plan the issue is confused by the fact that he numbered the pillars (interpreting them as bases), not the heads, whereas in his text, the numbers refer to colossi. His numbers 5 and 6 apply to the (pillars pertaining to the) two colossi found by Pillet, but the position of the two in relation to each other is not revealed. By studying Chevrier’s sketch plan it becomes apparent that his nos. 3 and 4 relate to two pillars where two heads described in his text were found together; a third head said to have been found two meters to the west must therefore be the one near his pillar no. 2. Four unspecified heads east of the canal correspond to his pillars nos. 7–10. An intriguing reference concerns:

- a statue base with toes (“base avec la partie antérieure des pieds”—see Chapter 2, L59).11

The statues had been provided with a back pillar carved out of one and the same piece of sandstone (fig. 1.4). Chevrier refers to these back pillars as “enormous,” and he compares the sculptures with Osiris pillars. It was evident to him that attempts had been made to disengage these back pillars from the colossi in order to use them as building material. The area was strewn with chips resulting from this activity. The statues had originally been set along (“devant”) a wall, but they had been overturned and laid face down. At this point in time Chevrier was unsure as to whether he was excavating the façade of a building or a peristyle court inside one. Throughout his reports, Chevrier refers to the talatat pillars as “socles,”12 and there can be little doubt that he is implying that the colossi had been placed on top of them, in front of the said wall. This latter was built of blocks measuring 55 x 26 x 22 cm, approximating to what we now know as a regular talatat. Later excavations have revealed that this wall was indeed the foundation of a wall of decorated talatat, according to Chevrier set 1.7m deeper (“en contre-bas”) than the pillars,13 its thickness being the equivalent of four rows of blocks. This statement was later reassessed by Redford, who found that the wall consisted of five ranges of stones: three headers lined by an outer range of stretchers.14 Chevrier adds a cryptic phrase that is not discussed again: “Behind this wall the trench of the drain shows débris of sandstone derived from quarrying an entire building which extended south of the row of statues.”15 A possible explanation of what may have been in this area may be inferred from a suggestion by Nicholas Reeves: “The structural location [i.e., of the Gempaaten], to the north of the temple of Amun, was presumably balanced on the south by the king’s palace; this structure is mentioned in the texts but, since it will have been of mud-brick construction, no traces have survived.”16

Fig. 1.3 Cevrier's first plan (ASAE 26, 1926, p. 192).

Fig. 1.4 JE 99065 (D10) showing area where back pillar was removed.

At the end of the season, Chevrier had the area tidied up, leaving the neat, straight lines to the north which appear as a cross-hatched area to the left in his plan. To finish off, and to prevent clandestine activities over the summer, he excavated a small area on either side of the drain, discovering, on the east side,

- a head and torso (“un très beau fragment d’une nouvelle statue, compose de la tête et du torse jusqu’au coudes”) (B4?)

- and, on the west, another head (“sur le coté ouest . . . encore une tête”)17

In total, nine heads had been found that season along with numerous fragments. Chevrier adds that he has noted traces of color on the pieces (his fig....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Discovery

- Chapter 2. Catalog

- Chapter 3. Interpretation

- Chapter 4. Aesthetics

- Chapter 5. Pathology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Karakôl Numbers Concordance

- Illustration Credits

- Index