- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Egyptian Peasant

About this book

Egypt has changed enormously in the last half century, and nowhere more so than in the villages of the Nile Valley. Electrification, radio, and television have brought the larger world into the houses. Government schools have increased educational horizons for the children. Opportunities to work in other areas of the Arab world have been extended to peasants as well as to young artisans from the towns. Urbanization has brought many families to live in the belts of substandard housing around the major cities.

But the conservative and traditional world of unremitting labor that characterizes the lives of the Egyptian peasants, or fellaheen, also survives, and nowhere has it been better described than in this classic account by Father Henry Habib Ayrout, an Egyptian Jesuit sociologist who dedicated most of his life to creating a network of free schools for rural children at a time when there were very few. First published in French in 1938, the book went through several revisions by the author before being translated and published in English in 1963. The often poetic yet factual and deeply empathetic description Father Ayrout left of fellah life is still reliable and still poignant; a measure by which the progress of the countryside must always be gauged.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Egyptian Peasant by Henry Habib Ayrout in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Changelessness

The fellahin, that is to say the rural proletariat of Egypt, whose life is the subject of these chapters, represent something more than a mere class. As a uniform, autochthonous mass, constituting more than three quarters of the total population, they may be rightly called the people of Egypt.

This people, which probably produced the first civilization (or in any case a civilization of great originality which lasted for thirty centuries), offer no less original powers of survival and persistence.

They have changed their masters, their religion, their language and their crops, but not their way of life. From the beginnings of the Old Kingdom to the climax of the Ptolemaic period the Egyptian people preserved and maintained themselves. Possessed in turn by Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Turks, French and English, they remained unchanged. Even today the fellahin play no part in the Egyptian renaissance or the movement for progress.

At first they were pagans carrying totemism to the point of zoolatry; then, for six centuries, they were Christians attaining often the perfection of asceticism or martyrdom. They made few difficulties about accepting Islam, and yet thirteen centuries of Islam have done little to change their religious psychology.

A receptive people, yet unyielding; patient, yet resistant. Although they dwell at the crossroads of international traffic, in a country which has been the scene of some of history’s most decisive events, they remain as tranquil and stable as the bottom of a deep sea whose surface waves are lashed with storms.

The map of the world has been changed a hundred times by human events, and with it the map of Egypt. But fundamentals have not changed; the fellahin have not changed. They have borne the strain of changes and have not flinched.

Violent and repeated shocks have swept away whole nations, as attested by the ruins of North Africa or Chaldea, standing deserted in fields inhabited by alien peoples. But the fellahin have stood their ground.

The history of Egypt includes more than its share of wars and revolutions, but the people have taken no part in them. Only once, between 725 A.D. and 830 A.D., are we told of risings in the countryside. Crushed by the taxation of their Arab conquerors, the fellahin abandoned their homes and settled elsewhere. These evasive movements became almost general, but the repression was so terrible that the Copts decided on open revolt. Six times they rose, but without unity or plan. Six times they were savagely put down. They are not the stuff of which rebels are made. And even in revolt, the mass of the people remained unaffected.

They are as impervious and enduring as the granite of their temples, and once the form is fixed, they are as slow to change as were the forms of that art. The glances of their daily life which we get from Pharaonic tombs or from Coptic legends, from the Arab historians or the Napoleonic expeditions, from the earlier English explorers or the travelers of our own day, seem to form one single sequence. One has the impression that all these scenes, separated by centuries, only repeat and confirm each other.

This is not simply an impression. We see the same agricultural implements—plow, water wheel, winnowing fork, sickle and straw basket; the same way of treating the body—tattooing, circumcision, the use of kohl and henna, plucking of hair; the continuance of many marriage and funeral customs. Following the pages of Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Maqrizi, Vansleb, Pere Sicard and Volney, we find still the same fellah. No revolution, no evolution.

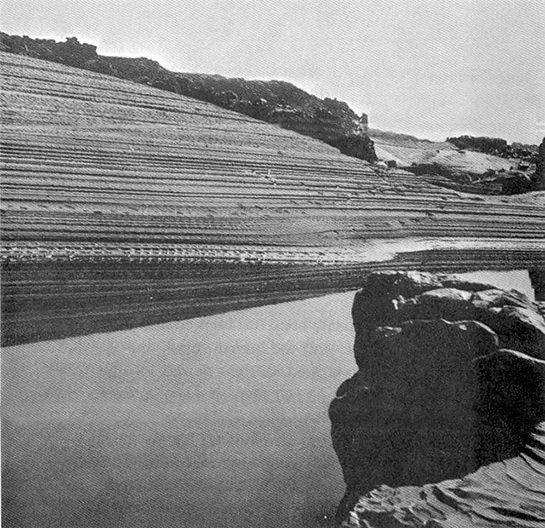

And here is the heart of the problem. How can we explain this physical stability, this psychological and social changelessness, this enduring, extraordinary sameness in a race of men? The answer is in the soil—just as one might explain the uniformity of Egyptian art which has been inspired by assimilation to the environment. The level ridges and steep cliffs on the edge of the Arabian and Libyan deserts have inspired the long, low, massive outlines of the Pharaonic temples as well as the level cornice which finishes them. The papyrus, lotus and reeds which grew along the Nile were stylized in the pillars and capitals we call papyriform, lotiform or proto-Doric.

For ages past, an intimate bond has been established in the Nile Valley between nature and the human mind, and the successive masters of Egypt have used all their powers to draw this bond even tighter.

The fellah found himself between the soil and the masters of the soil, between the anvil and the hammers. Yet by the nature of his life, he remained nearer to it than to them, and their hammer blows beat him still closer to the soil. This union is so real that the fellah’s masters not only own the soil but also own the fellah. Hence the fellahin owe their astonishing stability and uniformity to their association with the soil of Egypt, an element no less stable and uniform. Between these two there has grown up a bond both firm and elastic; a balanced self-sufficient interdependence which neither crises nor governments can disturb. Here, in the words of Sully Prudhomme, is found: “that stern and immemorial wedlock of a people and a land which have made each other.” This unbroken contact of people and land has brought about a continual process, a play of action and reaction, likeness and difference, which strengthens the indissoluble union of the two. On the one hand there is nature, the physical environment in its broad sense—climate, sunshine and above all the water and sediment of the Nile, its flora and the surrounding deserts. On the other hand, we have man, the fellahin—walled in by their habits as well as their villages, dense and gregarious, but isolated and unorganized—closer to the soil which they understand than to the state of which they know nothing.

Fig. 1. The Nile bank after the receding flood.

But at all costs, let us avoid here even the appearance of determinism. The fellah is no more the product of the Egyptian countryside than the Egyptian countryside is the product of the fellah. The question is not one of inevitability or of any determining influence. Man is free, and this freedom is to be defined as “power of self-determination.” Man is free, and agriculture remains contingent upon his will. There are infinite possibilities, among which the will of man—not of the fellah, to be sure, but of his master—chooses this or that, according to circumstances. At one time, the vine was grown on Egyptian soil. Grapes make wine, and the Koranic prohibition destroyed the vineyards. Not long ago, vast areas were planted with tobacco, but the government forbade this. Maize [Indian corn], of American origin, and cotton, introduced in the nineteenth century, are now among the chief crops. Tomorrow a new crop may cover the field. No law of necessity, whether of climate or soil, determines finally even the agriculture of Egypt, much less, then, human life. At the same time the climate and vegetation exert their characteristic influence on those who live in and on it.

In the case of town dwellers and industrial workers the bond between man and nature is much looser; the impress of the physical environment is softened and neutralized by the stronger social, civil and political influences. This renders these groups much less stable, but more progressive.

The peasant, on the other hand, is molded directly by the soil. Without our subscribing to any environmental determinism, it will become clear that the monotony, uniformity and productivity of the Nile Valley have their exact counterpart in the characteristics of the fellah community. The two are not parallel, but correlative. They meet and crystallize in the manner of life, which is at once a social and a geographical phenomenon. It will also become clear that the water and mud of the Nile enter into, and in a large part explain, the whole life of the fellah, his work and his home, his body and his temperament, and lend him both their qualities and their defects. It is because the fellah is “buried” in this mud that it has become so fertile. Egypt, gift of the Nile, is no less the gift of the fellah. It is because this soil is incarnated in the fellah that he himself is enduring, but also so material and so stagnant.

Progress therefore can only come from some form of release, of emergence, from education, in its original sense of drawing out potentialities. The duty of society is to liberate his spirit from its stifling covering of mud, to cleanse him of the defects of the soil, while leaving him its good qualities. The initiative can never come from him, numbed and powerless, but only from the classes which overshadow him, from the elite, who with their riches of mind and money can vitalize him. In this dough the leaven of intelligence and charity must work.

The following chapters will illustrate in more detail these general remarks and lead us by the logic of facts to the human conclusion we have sketched here.

2. Egypt, an Agricultural Country

Industrialization is a common topic in Egypt today. Since World War II, progress has been as widespread as it has been rapid. An industrial proletariat has emerged, with its legislation and its problems. Yet, properly speaking, Egypt is not an industrial country. It is, and will be for some time to come, agricultural, because of its structure and resources.

By reason of its flat surface, its rich damp loam, the river and the dry warm climate, the Nile Valley is geographically suited for intensive and extensive agriculture, and its soil can bear crop after crop without failing.

Were it not for the fertilizing Nile, Egypt would present nothing but a wide expanse of sterile sand and stone. Like her neighbors, Libya and Arabia, she would be only a poor land of nomads and shepherds.

Though the Nile does not rise in Egypt, this country enjoys the maturity and fullness of the great river. It passes through her boundaries, after a journey of 3,000 miles, with a rich load of silt drawn from the most varied types of soil. Year after year it is renewed, and its rise and fall is Egypt’s pulse.

Ever since the last phase of the quaternary, the silt has been brought down from the south and deposited by the Nile in alluvial strata, over the flat edges of its bed, spreading out in widening layers at its mouth and pushing back the sea. Over the limestone and granite rocks and sand a layer of black earth from 30 to 90 feet deep has been created.

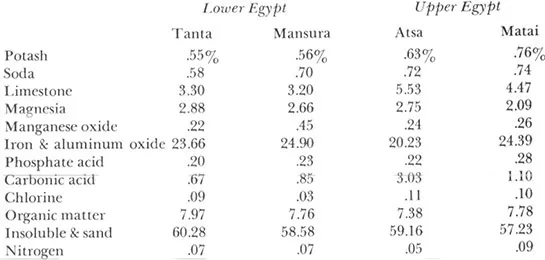

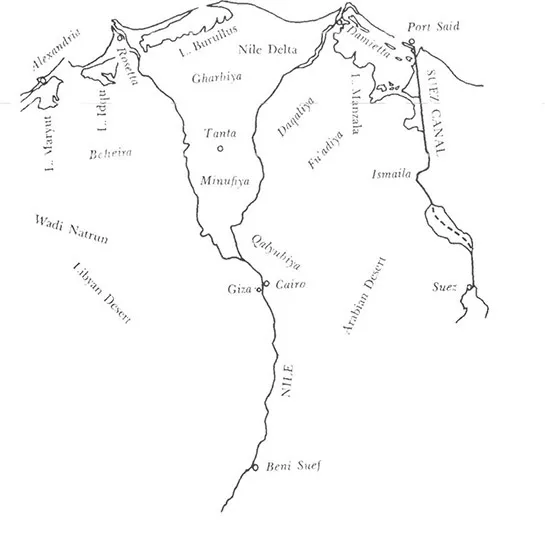

Unlike the soil of most agricultural countries, the composition of this deposit is substantially the same everywhere. It is an amalgam of fine particles carried down by the Blue Nile and White Nile, consisting of coarse and colloidal clay, with an admixture of salts. Its high mineral content (see table) has an important influence on the life of the fellah. Once deposited, this soil is continually enriched and irrigated by the flood of the Nile or by canalization, but always under the control of man. The very ancient system of basin irrigation, still in use in over a million feddans,* consists of discharging the water at flood time through channels onto great basin areas of land, hawds, which are surrounded by dikes. The water slowly drains away, saturating the land and depositing a layer of the fine silt with which it was laden before flowing into the basins. Each feddan thus receives some 1,700,000 gallons of water and eight to nine tons of silt. Immediately after the water has drained off, around November, the crops are sown. They are then left to ripen until harvest-time without any need for further irrigation. The field then is left fallow until the next flood. Often, however, these basin farmers make use of underground water by means of pumps, wishing to produce a summer as well as a winter crop. In fact, pumps are now so common in these districts that they have modified the system of cultivation.

MINERAL CONTENT OF THE NILE IN FOUR CITIES IN LOWER AND UPPER EGYPT

Fig. 2. The Nile Valley

Perennial irrigation is the system now in use, since 1840, in all the Delta and in the greater part of Upper Egypt. It has been made possible by some remarkable works of engineering, the most notable of which is the Aswan Dam. The Nile no longer completely floods the land. Its water is stored in reservoirs and distributed by barrages into a network of canals which it fills throughout the year. The system works thus: (1) At high Nile, from August to October, the fields are not submerged but only irrigated, and bear the fall crop, or nili. (2) From November to April the waters are falling; the land, still moist, receives enough water for the winter crop, or shatawi. (3) At low Nile, April to July, the reservoirs are opened to allow irrigation, which gives the summer crop, or sayfi.

To yield its fruits, the land needs not only water but also air. This is carried out by the wide cracks made by the sun on the fallow land, which is thus freed of excess salts and mellowed by allo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreward

- Contents

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Introduction by Morroe Berger

- Author’s Introduction: On Understanding the Fellah

- 1. Changelessness

- 2. Egypt, an Agricultural Country

- 3. Landowners and Government

- 4. The Fellah at Work

- 5. The Physical Fellah

- 6. The Village and the Peasant Group

- 7. The Fellah’s Home and Family

- 8. Traditions of the Soil

- 9. The Psychology of the Fellah

- 10. The Distress of the Fellah

- Epilogue: Progress

- A Critical Bibliography

- Glossary of Arabic Terms

- Back Cover