- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book moves beyond superficial generalizations about Cairo as a chaotic metropolis in the developing world into an analysis of the ways the city's eighteen million inhabitants have, in the face of a largely neglectful government, built and shaped their own city. Using a wealth of recent studies on Greater Cairo and a deep reading of informal urban processes, the city and its recent history are portrayed and mapped: the huge, spontaneous neighborhoods; housing; traffic and transport; city government; and its people and their enterprises.

The book argues that understanding a city such as Cairo is not a daunting task as long as pre-conceived notions are discarded and care is taken to apprehend available information and to assess it with a critical eye. In the case of Cairo, this approach leads to a conclusion that the city can be considered a kind of success story, in spite of everything.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Cairo by David Sims in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Urban Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Imaging Cairo

Modern Cairo is certainly no backwater, judging by the amount of commentary that has been and continues to be poured out about it. The attention Cairo receives is found in books on Cairo itself, in articles, in television programs, on websites, in films on particular aspects of the city, and in works about Egypt and the Middle East, in which Cairo figures more or less prominently. Efforts range from serious journalism to guidebooks and travelogue impressions and from obscure academic material to obtuse development reports generated by aid agencies. There is also a large body of fiction whose stories are located in Cairo, some of it very good and well-known and some of it superficial and self-serving. Except for the fiction, most of the material is produced by western authors and institutions, and it is no exaggeration to say that the western optic, especially the Anglophone one, seems to predominate. Commentary on Cairo by Egyptians is rich and varied, but is found mostly in the newspapers, on television, and in local journals, rarely in books.1

Obviously, as a collective whole such sources can aid a reader in gaining an understanding of the city and how it works. But who has the time and patience to synthesize, even if information overload doesn’t occur? In addition, the impressions gained are often superficial and sometimes completely incorrect, since ‘out there’ is a lot of material colored by preconceptions and myths. This can even be found in material that is ostensibly well-grounded in Cairo and its manifestations, but it is more often found in the copious transnational literature that throws in snippets about Cairo while advancing global truths seemingly valid across cities, across countries, and even across continents. There is too much of the need to neatly package and quickly extrapolate to the global, and in the process necessarily to stereotype, lose track, and objectify.

This chapter tries to set the scene, going through the most common types of imaging to which Cairo is subject. The aim is to inform the reader that there are numerous ways Cairo can be ‘taken’ and observed, and to provide a kind of gentle forewarning of some of the more common pitfalls and distortions found in the literature.

Cairo as History

The single strongest pull in the imaging of Cairo is probably the city’s historical dimension. And Cairo certainly has a lot of history, over four thousand years of it if Memphis and the Giza pyramids are considered part of the city, and over one thousand years even if Cairo’s history is considered to have begun only in the Fatimid era. In fact, it could be said that there is a whole industry, curiously dominated by American and French scholars, which looks just at Islamic Cairo. It even seems sometimes that the most important commentator on Cairo is the fourteenth-century chronicler and urban observer Ahmad ibn ‘Ali al-Maqrizi.

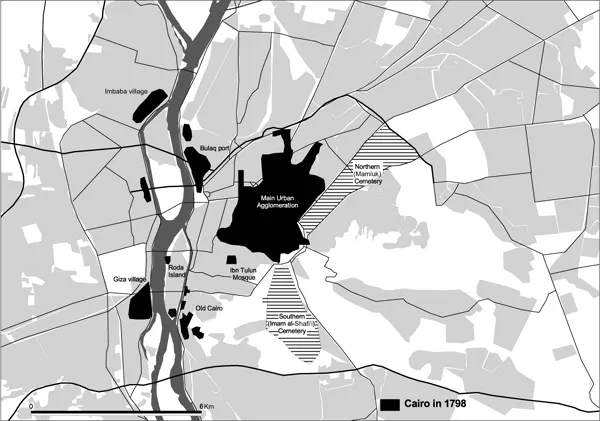

It is worth remembering that, although Cairo certainly has a proud historic past, at present the parts of the city that can be considered historic (that is, those that existed at the time of the French occupation in 1798) represent only a minuscule fraction of the whole. Currently the population of these areas (see Map 1.1) does not exceed 350,000 persons, or 2 percent of Greater Cairo’s total of over seventeen million inhabitants. It should be added that the population of these small areas continues to decline, and if the government has its way, historic Cairo will soon become a sterile open-air museum with little else but theme-park embellishments and tourist shops.

Although historic Cairo is now an almost insignificant part of the modern metropolis, Cairo as history seems to trump the literature. In the last fifteen years three substantial books have appeared that look specifically at Cairo—André Raymond’s Cairo: City of History (published in 1993 in French, and in 2001 in English), Max Rodenbeck’s Cairo: The City Victorious (1998), and Maria Golia’s Cairo: City of Sand (2004).2 Each tries to see the city as a whole, and each includes descriptions of contemporary Cairo. Yet in each the historical emphasis is at the forefront, if not overwhelming.

Raymond’s book is the most historic, devoting only one chapter of some thirty pages to Cairo’s development over the 1936–92 period. And this chapter is predictably named “The Nightmares of Growth.” It concentrates on “galloping population growth,” wholesale urban expansion on precious agricultural land, the “frenetic growth” of what had been genteel neighborhoods, the “near-paralysis of traffic,” and deplorable infrastructure services. Raymond devotes only two pages to the phenomenon of informal or spontaneous settlements around Cairo, which flourish “without the help of any planning, in agricultural areas that one would wish to preserve,”3 focusing instead on laments for the decline of the historic quarters and the ugliness of recent architecture. Raymond seems to see nothing good in recent developments, implying that his “city of history” is losing its soul. He concludes:

Map 1.1. Cairo built-up area in 1798 (from Description de I’Égypte) compared to 2009.

But Cairo risks becoming an ordinary city, another example of the vast conurbations proliferating throughout the world.… The population threat is still present, poised to sweep away the fragile barriers that technicians and politicians have managed to erect to direct its flow. In the past demographic growth has been an asset to Egypt, giving it power, prestige, and authority. Today it is a mortal danger. Cairo long played the part of safety valve for Egypt’s population growth. Tomorrow it could be its detonator.4

This gloomy assessment was published in 1992, when Greater Cairo had just eleven million inhabitants. Today it has over seventeen million and is still nowhere near detonating.

Max Rodenbeck’s book on Cairo is also unabashedly historical, and the first two-thirds present a very readable and insightful historical timeline that starts in earnest with the Arab conquest of Egypt in ad 640 and the establishment of al-Fustat. The last third of the book covers modern Cairo since the 1952 Revolution, going through the rule of Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak, and focusing on Egypt’s changing fortunes and social dynamics and how they played out in Cairo. Religion and fundamentalism, political games, bloated bureaucracy, foreign aid, riots, Sufi mulids, coffee houses, class hierarchies, the hopeless education system, garbage and the zabbalin, song and film, are all subjects for observation. Cairene kindliness, stoicism, humor, and wit in the face of economic stagnation and chaos rightfully claim pride of place. Rodenbeck offers few generalizations, but he does sit back and muse, quite accurately: “On the surface Cairo’s ways of coping seem hopelessly tangled and sclerotic. They can be maddening.… By and large, though, the city’s mechanisms work.… In richer cities formal structures, rules, and regulations channel a smooth flow of things. In Cairo informal structures predominate.”5

Rodenbeck never completely abandons the historic take on the city, even when discussing modern facets. He is clever at intertwining the old with the new. Thus Nasser’s autocracy is compared with that of the Mamluks, modern Cairo’s cavalier attitude to garbage is compared to a similar pharaonic nonchalance, today’s rampant bribery is compared to legal knavery recorded on tomb reliefs from the New Kingdom as well as to medieval Cairo’s corrupt judges and bribed witnesses, and present-day funeral obsequies are compared to both the pharaonic and Islamic preoccupation with death. These comparisons might help provide continuity in a take on Cairo that is more or less biographical, but it does not in itself explain how modern Cairo grows and works. For example, although the book was published in 1998 when almost half the city could be considered informal, the phenomenon of informal urban development and its ascendancy in Cairo’s landscape is hardly mentioned, except in a quote from Asef Bayat on the informal city’s style of “quiet encroachment” and a reference to the “higgledy-piggledy burrows of Bulaq al-Dakrur.”6 To Rodenbeck, as to many other observers, the hard life of the poor is found in an amorphous geographic landscape called “the Popular Quarters,” which combine new informal Cairo with older tenement and historic areas.7

Maria Golia’s book is less historic than either Rodenbeck’s or Raymond’s. In the preface she poses the question: “Some of us wonder, watching Cairo teeter between a barely functional glide and an irretrievable nosedive, what keeps this plane in the air? … How and why, given some of the most grueling, incongruous conditions imaginable, Cairo retains its allure and its people their sanity.”8 She aims at looking at “Cairo’s broader present moment, its giddy equilibrium and unfolding contemporary nature,” pursuing lines of inquiry about Cairo’s millions and their “grace under pressure.”9 Golia bravely tries to do just that, but even so, she also cannot avoid the historical spin. One of her five chapters is devoted entirely to the city’s history, and references such as “the arc of fourteen centuries” pepper the text.

At one point Golia asks “Perhaps today’s greatest riddle is not so much ‘where is Cairo headed?’ as ‘where is Cairo at all?’ Is it in the old quarters, or the remnants of belle époque downtown, or in the new middle-class areas on the west bank, or in the satellite cities of the desert? Or is the real Cairo to be found in the myriad hovels in which most of the people actually live?” Except for her pejorative and incorrect description of informal Cairo as a collection of hovels, this is a good question! Unfortunately she doesn’t really answer it, except to ask another question, which turns back to history: “Does a collective hallucination sustain the image of an ancient and venerable city when it is in fact disfigured with slums and crass consumerism?”10

Even Janet Abu-Lughod, who describes the orientation of her well-known 1971 book on Cairo as “social and contemporary rather than historical and architectural,” seems unable to escape from being partly tied down by a thousand years of history.11 Over one-third of her book is devoted to the Islamic and Khedivial city, up to roughly the time of the First World War. However, the rest of the book investigates the formation and growth of the “contemporary city,” which roughly covers the 1920 to 1960 period.

Cairo as Nostalgia

Closely related to Cairo as history is the nostalgic view of the glories of a more recent past. There are many Cairenes as well as foreigners who look back to some perceived golden period, usually through a blinkered memory conditioned by revulsion at what Cairo has since become.

Actually, what is perceived as Cairo’s golden period is in the eye of the beholder, and it is possible to ride through time on the back of this nostalgia. Although no one still alive remembers Cairo’s belle époque (generally considered to have spanned the 1870 to 1925 period), there has recently been an outpouring of material about its architecture, enterprise, and social life.12 This view is frequently combined with a stubborn nostalgia for the Cairo that existed before King Farouk was overthrown in 1952. Cairo has a surprising number of unabashed royalists who see the 1930s and 1940s as the heyday of a sophisticated capitalist Egypt untainted by the self-serving officers of Arab socialism. From time to time glossy retrospectives of royalty and their social life appear.13 The fact that much of what is now ascribed to the Nasser regime actually had its antecedents under Farouk, such as rent control, social housing, and even the oft-maligned Mugamma‘ al-Tahrir, the central government services complex in Tahrir Square, downtown Cairo, is conveniently ignored. Moving to still more recent times, there are many who look back nostalgically to the innocence of the early revolutionary period, 1952–62, with the flowering of national pride expressed in cinema, song, prestige industry, and Cairo’s undisputed primacy as the political capital of the Arab world; that is, a period before all those ‘peasants’ flooded into the city and ruined everything.

This nostalgia has translated into a number of attempts to preserve the patrimony of older buildings in the downtown area. In 2008 the façades of older buildings began to be renovated by Cairo Governorate and the Ministry of Culture’s al-Tansiq al-Hadari (‘urban harmony’) division. At the same time an important developer quietly began to buy up some downtown properties of particular architectural merit. There are even brave if fitful efforts at revitalizing the cultural scene of wust al-balad. In one of the strangest manifestations of nostalgia, a couple of real-estate developers are now promoting exclusive gated communities that seem, at least architecturally, to be recreating belle époque Cairo.14 Only in the fine print is it discovered that these projects are in bleak desert locations many miles from the city proper.

The important point about the nostalgic take on Cairo is that it is largely referenced to and compared with what Cairo is today. And this modern Ca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword Janet Abu-Lughod

- Introduction

- 1 Imaging Cairo

- 2 Cairo is Egypt and Egypt is Cairo

- 3 A History of Modern Cairo: Three Cities in One

- 4 Informal Cairo Triumphant

- 5 Housing Real and Speculative

- 6 The Desert City Today

- 7 Working in the City

- 8 City on the Move: A Complementary Informality?

- 9 Governing Cairo

- 10 Summing Up: Cairo Serendipity?

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index