- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

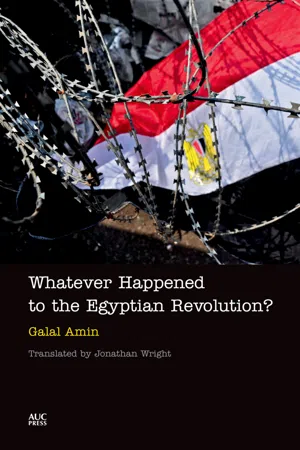

Whatever Happened to the Egyptian Revolution?

About this book

In his latest exploration of the Egyptian malaise, Galal Amin first looks at the events of the months preceding the Revolution of 25 January 2011, pointing out the most important factors behind popular discontent. He then follows the ups and downs (mainly the downs) of the Revolution: the causes of rising hopes and expectations, mingled with successive disappointments, sometimes verging on despair, not least in the case of the presidential elections, when the Egyptian people were invited to choose between a rock and a hard place. This is followed by an outline of a possible brighter future for Egypt, based on a more balanced and faster growing economy, and a more democratic and equitable society, within a truly independent, modern, and secular state.

The story of what happened to the 2011 Revolution may be a sad one, but if viewed within the larger context of Egypt's economic and social developments of the last century, on which the author's previous books threw very useful light, it can be regarded as one important step forward toward a much better future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Whatever Happened to the Egyptian Revolution? by Galal Amin, Jonathan Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Worse than Unemployment

1

Whenever I returned to Egypt after an absence of any length, as soon as I set foot in the airport, I would be struck by some manifestation of a class-based society: junior staff waiting for senior staff, someone carrying passports for an important group of people and completing the passport formalities on their behalf so that they could get out of the airport before anyone else, or the staff of tour companies, mostly university graduates, who could not find better employment than holding up a sign with their company’s name for passengers to see, and so on.

As soon as I started putting my bags on the bus that takes you from the airport to the parking lot, two young men would appear from nowhere, then three of them and then four, all competing to help me and my wife carry our bags. Then, as soon as the bus stopped and I started taking the bags off, another four young men would appear from nowhere, competing to perform the same task.

I noticed that those competing to do this job didn’t look the way porters used to look in Egypt. They were better dressed and younger, but the look of degradation on their faces was more distressing than the facial expressions of the old-time porters.

In such situations I would usually feel guilty in a way I had not felt all the time I was abroad, because travelers in Europe, the United States, or even in other Arab countries never come across such situations. Yes, of course, there are rich and poor, but not in this way. Yes, society there can be divided into classes, but they do not have the same privileges for the upper classes that you see in Egypt from the first moment you arrive, or the same servility among those beneath.

Social stratification is a very old phenomenon, of course, whether in Egypt or the rest of the world, but it has not always created this feeling of guilt on one side or bitterness on the other, because until recently the upper classes believed sincerely that they deserved their lives of luxury, as they were of a different breed because they were from distinguished families or simply because they owned vast tracts of farmland. In most cases they considered their wealth and their distinguished status to be a sign of God’s favor, and until recently the lower classes took this explanation for granted. “Yes, we are of inferior stock, born to lowly families without status or land, which shows that we are out of favor with God for some reason or other,” they would tell themselves.

Over the past hundred years things have happened to undermine these ideas or greatly weaken them on both sides of the divide. Race, color, pedigree, history, and religion cannot justify these class distinctions. It’s all a matter of outright injustice, and what makes matters worse is that everything is now obvious: the poor all know exactly how the rich live, if not from the luxury cars they see in the street, then from television, and they know that the upper classes can obtain all this opulence only by cheating.

The sense of bitterness on one side and the sense of guilt on the other were bound to grow, even if everyone pretended otherwise.

“I know full well how you obtained your money or your job.” That’s what those stuck at the bottom of the ladder tell themselves, while the others, even if they never say so in public, know that they are basically impostors who got where they are by force or by fraud.

In such a climate it’s hardly surprising that we find plenty of things to complain about loudly: new and unfamiliar types of crime, sexual harassment, bigotry, religious fanaticism, and so on.

2

There were two young men standing at the movie theater entrance, neither of them more than thirty years old, and their only job was to check tickets. One of them might escort you into the theater to show you your seat. There’s nothing strange about that, but the surprise was the way they treated us, my wife and me, as soon as I gave them the tickets. I’ve come across such situations before, but every time the shock makes it seem like the first. From the first word they uttered it was clear they were thinking only of their tip. We had arrived half an hour before the film started, so they suggested we sit in the movie theater’s snack bar and promised they would come and tell us as soon as it was time to go in. I disliked the degrading way they were speaking and I found the situation most unpleasant: two good-looking young men wearing smart suits (no doubt the management required it) yet prepared to beg for tips in this manner.

I took another two steps and another young man of similar appearance came up to me, with a young woman in hijab next to him, helping him with his work. What kind of work was it? He was inviting me to take part in a competition, the gist of which I did not quite understand, but I gathered from what he said that if I won I would get a prize.

After recovering my composure I went back to one of the men who had met us when we came in and asked him a few questions:

“What’s he after, that man who offered me a prize?”

“He’s the agent for a travel company that’s trying to promote its business, and the competition and the prize are part of the promotion.”

“What did you study at university?” I asked him (I was almost certain he had a university degree).

He said he had a degree in computer science.

“And your colleague?”

“He studied commerce, in English,” he said.

“Are you married?”

“Yes, and I have two kids: a boy, two years old, and a girl of six months.”

“Do you live with your family or your wife’s family?” I asked.

“No, we live in a rented apartment.”

“How much is the rent?”

“Four hundred and fifty pounds a month,” he said.

“Don’t get upset if I ask how much you earn.”

“Two hundred pounds.”

“Does your wife work?”

“How could she work when we have two kids that age? And suppose my wife did go out to work, when would we be together, when I work from four in the afternoon until midnight?”

“Do you have another job in the morning?”

“No, because they sometimes ask me to work in the morning instead of the evening.”

Then I realized how important the tips were; not just important but a matter of life and death. Was it surprising then that this young man and his colleague should treat me in such a degrading manner? I left him and went to the restroom. I saw another man standing at the door waiting for me. This man differed from the others in age but not in the impression of degradation he conveyed. He was older and thinner and his face suggested he was malnourished. It was a familiar sight that nonetheless gave me an agonizing feeling with a touch of anger every time I saw it. Not anger with the man, but with what drove him to behave in this way.

The poor man didn’t know what he could do or what service he could offer me in order to get a reward. But he knew how important it was to get the reward, which he had done nothing to deserve. Was that precisely what caused the feeling of humiliation so evident on his face? I guessed that this man did not receive any wage whatsoever. If the movie theater owner was only paying the young ticket taker two hundred pounds a month, he had probably offered this man a choice between a job without a salary or no job at all, and the man had taken the job in the hope that customers would take pity on him.

This phenomenon is much more widespread in Egypt than we imagine: jobs that must number in the millions in what is called the service sector. Someone selling goods or a service knows that the buyer expects him to provide some small additional service, like the car owner at the gas station who expects someone to fill his tank instead of doing it himself, or the customer at the supermarket who expects someone to help him bag his groceries or carry them to his car, or the hotel guest who expects someone to come and carry his bags, or the passenger getting on a train who wants someone to show him to his seat, and so on.

But employers don’t want to cover the cost of providing these small services. Since they know that Egypt has millions of unemployed people looking for any work, they exploit their weakness by giving them a choice between remaining unemployed or doing these jobs for no pay (or for insignificant payment) and relying on their ingenuity in dealing with customers.

This phenomenon, which is now widespread in Egypt, is not an old one. It did not exist to any noticeable extent in the time of the monarchy, under President Gamal Abd al-Nasser, or under President Anwar al-Sadat. The phenomenon prevalent when Egypt was a monarchy was what economists call disguised unemployment. Men would work at way below their full capacity, but not in this peculiar position of intermediary between customers and employers. That was the case with the surplus labor in the countryside, and with peddlers and shoe shiners in the cities.

In the time of Abd al-Nasser disguised unemployment sharply declined as a result of agricultural reform and industrialization, though it gradually reappeared in the civil service and the public sector when the drive for industrialization lost momentum after the 1967 war with Israel. But in the time of Abd al-Nasser we did not see the pernicious phenomenon I’m talking about. Nor did we see it to any noticeable extent under President Sadat because of the job opportunities available through migration to oil-producing countries.

All these outlets have been firmly shut for the past quarter-century. The number of jobs in agriculture and industry is growing too slowly, the emigration rate has fallen sharply because of the fall in demand for Egyptian workers in oil-producing states, and the Egyptian government has withdrawn from the business of giving jobs to all graduates and is cutting expenditures in the hope that the private sector will do what the government used to do. But the private sector is in the state I explained above: its motto is supply and demand, whether of commodities or labor. If someone is ready to work for no wage, why pay them a wage?

Whenever I open the window at home in the morning I see a young man of about twenty-five from Upper Egypt. I know his life history well because I have met him so often in my street. I know that his father did the impossible to make sure he completed his secondary education and then to get him into university to obtain a degree in business. Now, after he and his father did everything possible to get him a job that matches his qualifications, he has ended up with the job of wiping dust off the fancy cars parked in front of the building opposite mine. His hopes, just like the hopes of the men I have already described, depend on the generosity of the car owners, but this generosity is not assured and cannot be calculated precisely so he cannot rely on it when deciding whether or not to get married, for example. There are other needs that are more important and more pressing, including sending some of what he earns to his mother, who has stayed in Upper Egypt.

After seeing the ‘workers’ at the movie theater, I recalled some statistics presented by a prominent economist, a specialist in employment and unemployment, as evidence that the employment situation in Egypt has improved. The economist stated proudly that the unemployment rate in Egypt fell from 11.7 percent in 1998 to 8.3 percent in 2006. I said to myself, “There’s something very strange about this, because the unemployed don’t keep waiting for jobs until they die of hunger. They have to find jobs of some kind to feed themselves and their families. After getting computer science diplomas or degrees in business studies and then completely despairing of life, they must have agreed to take on the jobs I have described, and so the eminent economist can then deduct them from the rolls of the unemployed, and the ministers of investment and economic development can mention them in their statistics as evidence of achievements in reducing unemployment. But how should one really describe the work they are doing?”

3

There is a new way to die, known to Egyptians only for the last twenty years or so. What you do is pay several thousand pounds to someone whose specialty is smuggling people to Italy or Greece, then you get into a vehicle along with a group of other desperate people, cross the border into Libya, and get on a rubber boat with about fourteen other people. The boat takes you to somewhere off the coast of Italy or Greece, then you leave the boat and rely on yourself in swimming to shore, in a place where you hope the coastguards will be few. You slip past the guards and find yourself in a country where one can work illegally, unlike in Egypt, where there are no jobs, legal or illegal.

The problem is that the rubber boat is vulnerable to the rough seas of the Mediterranean and the traffickers usually overload it with people, so there is a serious risk of drowning before you reach the coast of Italy or Greece. Many such boats have sunk in the last few years. One of the most recent drowning incidents involved seven young men from the villages of Zanqar and Nousa in Daqahliya Province who were trying to slip into Greece. One of the survivors said that the boat capsized only thirty yards off the Greek coast.

I say this is a new way for Egyptians to die, and of course I mean poor Egyptians because rich and middle-class Egyptians do not die this way. If they want to go to Italy or Greece, they get on a plane or a ship. It’s a new way for poor Egyptians to die because they used to die at home of hunger or of grief, or on the roads in bus accidents because the brakes were worn or the driver was exhausted from long hours at the wheel or from the stress of driving on Egyptian roads. When poor Egyptians did die of drowning, it would be on a ferry that was badly maintained or not seaworthy in the first place. For poor Egyptians to drown from a rubber boat that isn’t designed to cross the Mediterranean is what’s new, but it’s not the only new aspect of this way of dying.

There’s another important aspect: that the poor Egyptians who die this way are not usually illiterate. In fact, many of them have university degrees, and despite these degrees (or maybe because of them) they have not been able to find suitable work at a reasonable salary. When illiterate Egyptians leave their villages and decide to emigrate, they rarely go anywhere other than the Gulf countries or Libya, so they are rarely exposed to the danger of drowning off the coast of some European country. This way of dying is closely linked to the phenomenon of growing unemployment among graduates over the past twenty years, because they are the ones who feel the painful gap between their aspirations, reinforced by the education they have received, and the wretched reality of their lives and their inability to meet their most basic demands: a reasonable job and a home that enables them to get married.

4

In an old film by the famous Italian director Vittorio De Sica, made about half a century ago, there’s a story that’s as funny as it is moving. It’s about the conditions that prevailed in some of the poorest regions of southern Italy, where unemployment was common and finding rewarding work was just about impossible, and so it was impossible to get suitable housing. In order to obtain somewhere to live, some of the poor young men would resort to the following ruse: they would find an empty piece of state-owned land, bring anything they could find that could be used as a substitute for bricks or stone, and build a small room under cover of darkness and as quickly as possible. By daybreak the building would be done and the police could not do anything against them because the law banned the demolition of any building with a roof, except through complicated judicial procedures that the police considered to be pointless. What mattered was that the building should have a roof. If the police happened to arrive before the roof was complete, it was all over; the building would be knocked down and all the efforts of the unemployed young men would go to waste.

The reader can imagine how a very amusing film could be made on this subject. The whole story becomes as funny as it is tragic, like a game of cat and mouse between the poor and the police over whether the poor will be able to put the roof on before the police arrive. During this tragic game the poor often found it useful to assign someone as lookout, to monitor the police from afar and warn the others if the police were coming, whereupon they would quickly do something to trick them, either by trying to divert them to somewhere else or by covering the missing part of the roof with anything, even with newspapers or old rags. The attitude of the police toward them varied according to the temperament or mood of the policeman. There was one hard-hearted policeman who would insist on arresting them and demolishing the room, and another decent one who voluntarily looked the other way while they finished building the roof or who pretended that the roof was real when it was not at all, and so on.

Something similar happens every day in Cairo and for similar reasons. As unemployment has increased in Egypt, the number of people seeking jobs of any kind to keep body and soul together for themselves and their children has grown year by year. I noticed that the number of people doing what economists call marginal work has increased rapidly in recent years: shoe shiners, peddlers, and street traders with minimal stock of cheap goods and a daily turnover of no more than five or ten pounds, whose profits might be no more than a third or half of that amount, selling meager quantities of limes or tomatoes, a few loaves of bread, or a few blocks of low-fat white cheese, and so on. The police constantly harass them on various pretexts: that they are blocking the streets and obstructing traffic, that they are getting in the way of pedestrians on the sidewalk, that they are giving foreign tourists a bad impression of Cairo, or that they are a security threat if a senior official is on his way to or from work, and so on. So the police confiscate their goods: they pick up their crates and baskets and throw them into police trucks, and the tomatoes or limes spill into the street as the traders scramble helplessly to pick them up. Then they run after the police vehicles, begging for mercy and shouting that the police have taken all their capital (which in fact amounts to just a crate or a basket), and the answer they hear is that if they want they can recover their goods from the police station after all the necessary procedures have been followed.

In these police vehicles I have seen many kinds of ‘capital’: baskets of pretzels, shoe shiners’ boxes, various cheap children’s toys mixed up with combs and plastic mirrors that the owners a few moments ago were o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part_1 Causes of the Revolution

- 1 Worse than Unemployment

- 2 Appropriating Public Property

- 3 Bequeathing the Unbequeathable

- 4 Selling the Unsellable

- 5 Spurious Nationalism

- 6 A Police State

- Part_2 Reasons for Hope

- 7 Harbingers of Revolution

- 8 January 25

- Part_3 Reasons for Concern

- 9 A Revolution or a Coup?

- 10 The Mysteries of the Egyptian Revolution

- 11 Muslims and Copts

- Part_4 Prospects for the Future

- 12 The Economy

- 13 Democracy

- 14 Social Justice

- 15 Dependency

- 16 A Secular State

- Afterword: An Abortive Revolution?

- Index