eBook - ePub

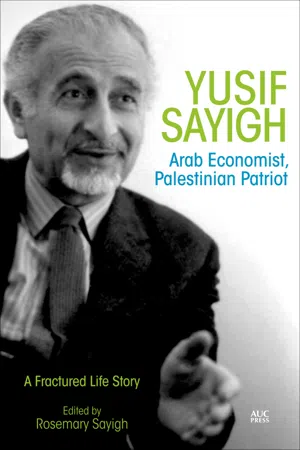

Yusif Sayigh

Arab Economist and Palestinian Patriot: A Fractured Life Story

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An acclaimed economist and lifelong Palestinian nationalist Yusif Sayigh (1916-2004) came of age at a time of immense political change in the Middle East. Born in al-Bassa, near Acre in northern Palestine, he was witness to the events that led to the loss of Palestine and his memoir therefore constitutes a vivid social history of the region, as well as a revealing firsthand account of the Palestinian national movement almost from its earliest inception. Family and everyday life, co-villagers, landscapes, pleasures, outings, schooling, and political figures recreate the vanished world of Sayigh's formative years in the Levant. An activist in Palestine, he was taken prisoner of war by the Israelis in 1948. Later, as an economist, he wrote extensively on Arab oil, economic development, and manpower, teaching for many years at the American University of Beirut and taking early retirement in 1974 to work as a consultant for a number of pan-Arab and international organizations. A single chapter on Palestinian politics provides insights into his later activist work and experiences of working as a consultant with the Palestine Liberation Organization to produce an economic plan for an eventual Palestinian state.

This fascinating memoir by a pioneer and major figure of the Palestinian national movement is a welcome addition to the growing literature on Palestinian life during the first half of the twentieth century as well as an account of some of the most pressing political and economic issues to have faced the Arab world for the better part of the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Yusif Sayigh by Rosemary Sayigh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Earliest Memories, Kharaba, 1918–25

The earliest recollection I have comes from Kharaba.1 My parents moved there after I was born in 1916 in the village of al-Bassa, near Acre in Palestine. I was about three years old. By then my mother had had another baby, Fuad, who died of some fever. I was lying with my head on my mother’s leg, looking up into her face—I was always very attached to my mother, all through, until she died—I went on feeling toward her like a baby needing his mother’s embrace. It was a very special relationship. So I was lying there, happy, looking into her face. Then I saw her tears falling. I said, “Mama, why?” and pointed to her tears. She said, “Because of your little brother Fuad who died.” So I said, “What do you mean?” She said, “He went to heaven.” That’s my earliest recollection. She was expecting then, and a few months later she brought another boy into the world, and they gave him the same name, Fuad. It’s unusual for families to give the same name of a child that has died. But my parents were both believers, and they felt that this was God’s gift to them, to replace the loss they had suffered.

That was in Kharaba, the village where we were living then, where my father was a preacher. He was not an ordained pastor; he still had no theological training. But he was a very religious man. His brother-in-law was a pastor, and he had gone to school at the Gerard Institute in Miyeh-Miyeh, near Sidon, where there was a great deal of religious teaching, since it was a mission school. It was his own decision to go there; he was an adult at the time and had his own means. He went to Sidon and asked about schools. Then he met the principal of the Gerard Institute, who was the same principal as when I went many years later, in 1929. He knew he wanted to be a pastor. Interestingly enough, my mother went to the girls’ school in Ain al-Hilweh, between Sidon and Miyeh-Miyeh.2 They overlapped in time, though my mother was several years younger than my father. It was because he was rather old for school, and she was rather young. They both graduated just before the war, I think, or in 1915. They married soon after.

They didn’t meet in Sidon. They met through Miss Ford, an American missionary who had her own mission.3 She had private means, and came to the region essentially to open schools, and to have preachers and pastors trying to convert people. She used to live in Safad. But it seems that she went to the Sidon School to recruit prospective teachers, and she met my father and my mother separately. My mother told me that Miss Ford—she was Mary Ford and my sister Mary was named after her—sent word to my mother to visit her in Safad. She had built herself a beautiful house in Safad, so beautiful that when the Israelis took over Safad, the military governor took it as his residence. It overlooks the Sea of Galilee and the beautiful hills around there.

So my mother visited Miss Ford, and Miss Ford said to her, “How about coming with me on a trip? I want to go to Hawran and see somebody called Abdullah Sayigh. I want to appoint him as preacher there.” My mother went with her. It was remarkable that my mother had such freedom. Indeed, going to boarding school was quite unusual for a young village woman in those days. It was partly thanks to a cousin from al-Bassa who had gone to the boys’ school there ahead of my mother—in fact, two cousins from different mothers, Wadi‘a and Jiryis Khoury, and they both went to Sidon School. They knew there was a girls’ school there, and here was a cousin who was likable and intelligent. They could tell that she could do well in school. So they encouraged her, and worked on her mother and father to let her go to school. It was amazing. I regret not having asked her for more details. All I know is that she went to school, and graduated the first in her class. My father was also the first of his class. He used to have such lovely presents that they gave him every year. The best present was an Elgin watch, one of those prestige watches, for being the first all through until the last year. Later he gave it to me when I went to Sidon School.

Miss Ford contacted my mother, and asked her to accompany her on this trip, and offered her a job as a teacher in a school she wanted to start up in Tiberias or Safad. As my mother had not yet accepted, she went with her to Hawran, and saw this man. She liked him, and he liked her very much. I don’t know when he proposed but certainly they married soon, in 1915, because I was born in 1916, on March 26.

The amusing thing is that in al-Bassa there were two or three young men who wanted to marry my mother, and when they heard that she’d got engaged to a Hawrani—Hawranis were looked down on then as backward; they didn’t wear western dress, people said they had lice—they tried to persuade my mother to change her mind. They also worked on my grandmother to influence her daughter. But either my grandmother was modern in outlook, or they did not succeed. So one of the cousins wrote a letter to my mother’s brother, who had emigrated to America, saying, “Your sister, an educated girl, the first one in the village to go to boarding school and get a diploma, has accepted to get engaged to a one-eyed Hawrani!”—about my father, who was quite handsome! My uncle was very hot-tempered, and wrote an angry letter to his sister. They sent him a picture of my father to prove that he had two good eyes. But my uncle went on being angry, and for many years he didn’t write to her. As for the man who wanted to marry her, I mean, I would commit suicide rather than be his son. Awful, almost illiterate. He had land. But my father was not without means.

Before my father was married he had two or three good horses, and one of them was coveted by a Hawrani from Busrah. This was in Kharaba. My father refused to sell it. One morning at dawn this man came and loosened the reins of the horse and led it out. My father heard the sound of its hooves and saw somebody going out of the gate, riding his own horse and leading the other horse by the reins. My father immediately got dressed. The man started galloping to get away from Kharaba as quickly as possible. My father took his rifle and ran to his other good horse, and galloped after him, shouting at him to stop. The man was ahead by a few hundred meters, and wouldn’t stop. My father fired at him, but didn’t hit him. Busrah wasn’t very far from Kharaba, so the thief soon got there. Realizing it was the man who wanted his horse, my father went to the mukhtar’s house, and woke him, and told him the story. He said, “Come right away and you’ll find my horse at this person’s house.” They went, and the man was brought to the mukhtar’s house and the elders of the village gathered there and apologized. My father got his horse back, and went home. It was my father who told me this story.

I was born in al-Bassa—this is moving back a little—because that is where they married. They were married there because my father wanted to escape conscription. He was caught in Hawran and made to join the Ottoman army, but he bought his way out—you could pay some gold coins and be released. But then he realized that they were coming back after a few months to grab people who had paid again. So he escaped and came to al-Bassa. He was already engaged to my mother at that point. They married in al-Bassa, and he stayed there. Then they grabbed him in al-Bassa. He hid but he was again caught and conscripted, and moved from one station to another until he ended up in Gaza. There he ran away again from his unit at night—apparently it was very cold—and he roamed about looking for a place to hide, until he found an oven. A big oven. Big households had large ovens, where you could throw in dozens of loaves at a time. There was no fire inside, but it was warm, so he slipped in. At dawn he heard some movement, and the moment he opened his eyes he saw a woman who was coming to light the fire and make bread. She was about to scream, but he said, “Sshh! Don’t worry! I’m hiding from the Turks.” She kept quiet, and I don’t know how he managed to hide and make his way all the way back to al-Bassa—from Gaza in the south to al-Bassa in the north—walking, or taking trains.

Then in 1918, when I was two years old, the family went back to Kharaba, because Miss Ford wanted my father to be a preacher and a schoolteacher there. My mother taught very briefly with Miss Ford, around the period when she took her to Hawran, in a school for girls. My knowledge of that period is very sketchy. My mother told me that she was twenty-three when I was born. That’s how I established that she was born in 1893. She used to say, “Your father was seven or eight years older than me,” so I also established that he was born in 1885. Later, when my father was in his seventies and eighties, he began to challenge this, and say, “La, immak heik [Your mother was like that], she wanted to tease me, to make me sound much older than her.”

In Kharaba my father became a preacher and we stayed there, near Deraa, which was within walking distance, even for a boy. Deraa was the seat of the emir of the Druze Atrash family. Kharaba in fact was more Hawran than Jabal al-Druze—there were two adjacent districts, Hawran and Jabal al-Druze.4 The capital of Hawran was Deraa, and of Jabal al-Druze it was Sweida. Kharaba was in between, the last village to the north, and near to Deraa. And beyond Deraa there was Sweida. It was an all-Christian village, mainly Orthodox and Catholic, with some Protestants. The first Fuad was born in Kharaba, and then the second Fuad. Then Fayez was born at the time when my father was planning—with the help of Miss Ford—to go to Jerusalem and study theology. I think he stayed there for about two years. It was a college of theology. Because he had read many theology books, and was mature, his training took a little less than two years. We went to Jerusalem, and he was ordained in August 1923.5

My father wasn’t from Kharaba originally; he was born in a village called Khirbet al-Sha’ar, not far from Damascus. That’s where his father, my grandfather, Yusif Sayigh, had settled with his own father, Abdullah Sayigh. Abdullah came from Homs and he had been a goldsmith, a ‘sayegh,’ but his real family name was Zakhour Kabbash. Because he was a goldsmith, it was simpler to refer to him as ‘al-sayegh,’ and then he adopted it as his name. He had only one son, my grandfather, Yusif. My grandfather lived in Khirbet al-Sha’ar with his father until his father’s death. Because he was well-to-do, my grandfather bought land—not much. My father’s share was something like 130 dunums, apart from the shares of his sisters—he had more land than them—and also sheep and horses. Then my father—I don’t know at what stage—or maybe it was my grandfather—moved on to Kharaba. Three of my father’s sisters were married in Kharaba. He had four sisters. One was married to a Christian in a Druze village called Salkhad, beyond Sweida.

So my father was ordained in 1923. On the way to Jerusalem, we passed by al-Bassa because my mother wanted to see her sister: she had a sister alive then, although she had lost two or three other sisters. She also had nephews, nieces, and friends. I don’t remember my grandmother. I think she died when my mother was in her last year of school.6 My grandfather died earlier. So we passed by al-Bassa and spent a few weeks there. It was there that I can first remember seeing a motorcar. There was a road from al-Bassa to Acre, and I remember a car coming, and everybody rushing to see it. Then in August, on our return to Hawran, we came back to al-Bassa, also for a visit, and from there we returned to Hawran via Lebanon. My father stopped in Sidon to see his teachers, and then on to Damascus, and then on to Kharaba. I don’t remember much of that trip. By this time he was a pastor.

Ah, I remember the reason why he wanted to go back via Beirut: to meet the head of the Protestant Church in Beirut, al-Qassees Mufid Abdul Karim, who later became the father-in-law of the Reverend Awdeh. He was a very respected, venerable person, and my father wanted the church of Beirut to help Kharaba build a church of its own. My father was ambitious: he wanted to have a proper church. There was an Orthodox and a Catholic church but not a Protestant one, only a smallish room that served as a church. Miss Ford provided some of the money, and Beirut helped by giving money toward the making of the benches. What I remember very clearly is that they also contributed a set of cups for Communion. The Beirut church was getting a new set of its own. So they contributed a set of hymn books and twenty or thirty of these little cups.

When we returned from Jerusalem after my father’s theology course, we happened to be in south Lebanon at the time when a census was taken. The people we were staying with in Sidon said, “Why don’t we list you as Lebanese like us instead of Syrians?” My father laughed, and they seem to have put down our names. So my father was not telling a lie when years later, in 1958, he applied for Lebanese citizenship. It was open to people who had been in Lebanon in 1923 when the census took place.

My father went back triumphant with this help and set about immediately building. He knew nothing about cement fixing or building, but he learnt. He went to Deraa and learnt from some contractors building there. As he had taken carpentry in school for five years, he made all the church benches himself as well as the pulpit, the windows, the doors—all the wood work, everything. Alone. He was a fantastic person when he was determined to do something, especially for the Lord. We don’t have any pictures of the church, but I remember it very, very clearly. There was a hawsh, an enclosed yard, around which were several rooms. That was where we lived, and also one of my aunts, the mother of Abu Victor, whose husband was a village doctor, tubb ‘arabi [Arab medicine]. The church was built on top of these rooms because they had no money to buy land, especially for a church. So my father said, “Why not build it on top and have a stairway leading up?” I remember my father saying that some old-fashioned members of the church said, “But you can’t build a church that is not on the ground floor.” “Why not?” They said, “It’s not decent.” It turned out that the Hawranis didn’t wear underpants—not even the women. This I discovered myself when I was a little boy, lying on the floor in our room, and the aunt who lived there came to visit, and stepped over me, and I could see that she had nothing on underneath. That’s why they were afraid that somebody would look up. My father said, “Well, you’d all better be careful about the way you walk, or wear underpants.”

So the church was built and equipped, and there was a big consecration. I think Miss Ford was there. But the completion of the church took time. I think that it wasn’t completed until 1925. But then of course it was destroyed. So my poor father had to build it all over again. It was burnt when the Druze attacked the village in 1925.7

The Village and Its Surroundings

My aunt’s husband read a lot, and it seems he was very effective as the village doctor. I remember him as a biblical figure with a long white beard and a hot temper like an Old Testament prophet. When I knew him he was already an old man, bent, with a stick. People would come to him from several villages for Arabic medicine. He had books about it. Every few months, his son Abu Victor would go to Sweida or Damascus and buy him powders and liquids from pharmacies. From them he composed liquids for coughs and powders for wounds or for stomach problems. He used one of those very tiny little scales, which he held with two fingers. He would put on one side grains of wheat for weights, and on the other the right proportion of the various powders. Or if he was mixing liquids he’d have a very small container, and put in the components in the right proportions. The powders were put in very thin cigarette papers and wrapped tightly as if molded, and people would swallow them.

There certainly wasn’t a bank in the village—I didn’t hear the word ‘bank’ until much, much later. There might have been one in Sweida, maybe a branch of the Agricultural Bank, an Ottoman bank, which had branches all over. The villagers used to borrow gold coins from each other. They would sometimes go to villages such as Busrah in Hawran, halfway between Kharaba and Deraa. Or if they needed a larger sum, it was usually from a merchant who supplied the borrower with seed, someone whom he knew and trusted. But of course there were guarantees and a very high rate of interest.

We went to those other places very seldom. I remember my mother used to nag about this. She felt imprisoned. My father had his work, his church, his congregation. Of course she had her children, but she wanted some breathing space, somewhere else to go besides Kharaba. She would say, “I wish we could go somewhere.” I remember going once or twice to Deraa with the family. I think we went with two donkeys and a horse. My father rode the horse.

Every now and then my mother would say to my father, “I wish we could leave, and take the children somewhere where they can get an education. Maybe you can find a job in a town, in Syria, in Lebanon, or in Palestine?” This would lead to some questions from me about al-Bassa. I was the eldest so I was the readiest to ask questions: “What is al-Bassa like?” I’d seen it in 1923 of course. They took me all over the place, to the fig trees, the pomegranate trees, the subbeir [prickly pears]. My mother would tell me about al-Bassa at great length, about going to the sea, and having picnics. I used to think, “My God! What are we doing here?” It was like comparing Paris to Nabatieh.

There was no bus there at all, no railroad. My father had a bicycle—it’s interesting how he learned to ride it. We had a threshing field, which was big and very flat, for doing the wheat. It was about ten minutes’ walk from the house. So he’d take the bicycle there, and start riding and falling and riding and falling until he mastered it. It was the only bicycle as far as the eye could see. There was a dust road, not a car road: there were no car roads to Kharaba at all. Jubayb was another Christian village near to us, about twenty minutes away by bicycle. My father would go there to preach, after preaching in Kharaba. He’d put on a pith helmet, one of those colonial things, because of the sun—there...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map of Mandate Palestine

- Introduction Rosemary Sayigh

- 1. Earliest Memories, Kharaba, 1918–25

- 2. Al-Bassa, 1925–30

- 3. Boarding School, Sidon, 1929–34

- 4. Tiberias, as a Boy, 1930–38

- 5. At the American University of Beirut, 1934–38

- 6. Ain Qabu, First Job, Work for the PPS, 1938–39

- 7. Teacher in Iraq, 1939–40

- 8. Life in Tiberias as an Adult, 1940–44

- 9. Jerusalem, 1944–48

- 10. Prisoner of War, May 1948–Spring 1949

- 11. “Life Will Never Be the Same without Her”: Umm Yusif’s Death, December 1950

- 12. Palestinian Politics

- 13. “Bread with Dignity”: Yusif Sayigh as an Arab Economist 301

- Notes

- Glossary

- List of Yusif Sayigh’s Publications