eBook - ePub

Egypt from Alexander to the Copts

An Archaeological and Historical Guide Revised Electronic Edition

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Egypt from Alexander to the Copts

An Archaeological and Historical Guide Revised Electronic Edition

About this book

After its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 bc, Egypt was ruled for the next 300 years by the Ptolemaic dynasty founded by Ptolemy I, one of Alexander's generals. With the defeat of Cleopatra VII in 30 bc, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, and later of the Byzantine Empire. For a millennium it was one of the wealthiest, most populous and important lands of the multicultural Mediterranean civilization under Greek and Roman rule.

The thousand years from Alexander to the Arab conquest in ad 641 are rich in archaeological interest and well documented by 50,000 papyri in Greek, Egyptian, Latin, and other languages. But travelers and others interested in the remains of this period are ill-served by most guides to Egypt, which concentrate on the pharaonic buildings. This book redresses the balance, with clear and concise descriptions related to documents and historical background that enable us to appreciate the fascinating cities, temples, tombs, villages, churches, and monasteries of the Hellenistic, Roman, and Late Antique periods. Written by a dozen leading specialists and reflecting the latest discoveries and research, it provides an expert visitor's guide to the principal cities, many off the well-worn tourist paths. It also offers a vivid picture of Egyptian society at differing economic and social levels.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Egypt from Alexander to the Copts by Roger S. Bagnall,Dominic W. Rathbone, Roger S. Bagnall, Dominic W. Rathbone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Égypte antique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de l'Égypte antique1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1.1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

1.1.a A new era

In 332 BC Alexander the Great of Macedon entered Egypt, then part of the Persian Empire, and gained control of it without opposition. Alexander stayed only for one eventful winter, in which he travelled to the oracle of Zeus-Ammon in Siwa and founded the city of Alexandria. In 331 BC he left, never in his brief lifetime to return, but his establishment of Macedonian rule in Egypt initiated a new era in Egyptian history. By the time Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BC, his conquests stretched from Greece eastwards to modern Afghanistan. The fiction of his empire was maintained in the recognition as king of, successively, Philip III Arrhidaios, Alexander’s half-brother, and Alexander IV, his infant son. Real power, however, resided with some of Alexander’s generals, who soon seized control of major parts of the empire. Among them, the late-blooming but cunning Ptolemy, son of Lagos, chose Egypt.

Egypt had been known to Greeks as far back as Homer as a region of fabulous wealth. Herodotus, ‘the father of history’, claimed to have visited Egypt in the fifth century BC. He called the Delta ‘the gift of the river’ to Egypt. Indeed, all Egypt was ‘the gift of the Nile’ (as Herodotus is often misquoted), for its renowned agricultural bounty and the rhythm of its years were dependent upon the great river’s annual flood. The Nile also lay behind the administrative, and sometimes political, division of Egypt into ‘Upper’ and ‘Lower’ halves. Lower Egypt was the Nile Delta, with Memphis at its apex as its chief political and religious centre. Upper Egypt lay to the south, and the region around Thebes was its major centre of power. South of Egypt, and providing a link with sub-Saharan Africa, lay the region known as Nubia. Beyond the limits of the Nile’s floodplain lay deserts, their edges sharply defined: the stony, mountainous Eastern Desert with its exceptional mineral wealth and network of roads to ports on the Red Sea (Chapter 10), the sandy Western, or Libyan, Desert with its extensive oases (Chapter 9), and the fertile depression called the Fayyum (Chapter 5).

Bibliography: Bowman 1986; Watterson 1997.

1.1.b Before the Ptolemies

Macedonian rule certainly brought innovations to Egypt, but there were important continuities from the pharaonic past. In the spheres of administration, religion and architecture, change occurred over centuries rather than decades. Egypt after Alexander can only be understood properly through appreciation of thousands of years of pharaonic antecedents. We start, however, with the first significant Greek involvement in Egypt, during Dynasty 26 (664–525 BC). Dynasty 26 arose in the wake of four centuries of fragmentation and foreign domination after the end of the New Kingdom and marks the beginning of the ‘international’ epoch of Egyptian history which is called the Late Period. Its founder was Psammetichos I, whose base was Sais in the western Delta; hence this dynasty is called the Saite dynasty. While the Assyrian king, whose client he originally was, was preoccupied closer to home, Psammetichos gained control of the entire Delta by 660 BC, and by 656 BC he had become master of all of Egypt.

Although Psammetichos relied on diplomacy more than force, foreign mercenaries – principally Greeks, Jews and Phoenicians – played a critical role in his advance. Throughout the Saite period, these troops protected the state not only from external threats, but also from the strong, indigenous warrior class (the machimoi), which was predominantly of Libyan ancestry. Of course mercenaries can cause problems: there were revolts under the pharaoh Apries, and the resentment of the machimoi towards the privileged position of Greeks and Carians contributed to his overthrow by Amasis. Egypt’s trade links with Greece and Phoenicia also developed significantly during the Saite period. Greek settlement was permitted at Naukratis, which was made the designated trading centre for all Greek commerce. An increase in the importance of Eastern trade is suggested by the canal from the Nile to the Red Sea that the pharaoh Necho II began to construct, which was completed under the Persian king Darius I.

Despite a web of alliances with Near Eastern and Aegean states, Amasis and his son Psammetichos III were not able to fend off the new ‘world power’, Persia. The Great King Cambyses defeated Psammetichos III at the battle of Pelousion in 525 BC, and Egypt became a part of the Achaemenid Empire. On Cambyses’ death in 522 BC, Egypt revolted, but Cambyses’ successor Darius I was able to regain control by 519/18 BC. Rebellions continued sporadically throughout the Persian occupation, but Egypt still contributed resources to the empire, including men and material for the attacks on Greece by Darius and his successor, Xerxes. Herodotus’ Histories, which recount these attacks and the background to them and devote a whole book to Egypt, are an important, though sometimes controversial, source for the history of the Late Period.

Although Egypt was a ‘satrapy’ (province) of the Persian Empire, the Great King was defined there in much the same vocabulary as a pharaoh. Under Cambyses and Darius, we find sensitivity to Egyptian traditions in administration and religion, although Xerxes seems to have been less tactful. In 404 BC another ruler originating from Sais, Amyrtaios, was able to free Egypt from Persian rule and inaugurate the last ancient period of Egyptian independence. The rule of Dynasties 28 to 30 was characterized by instability and the struggle for survival, both internally and externally. Inside Egypt, the Greek mercenaries and the native priests vied for power. All but one of the pharaohs in Dynasty 29 were overthrown. Beyond Egypt’s borders, Persia remained an omnipresent threat, and despite Egypt’s diplomatic and military efforts, there were frequent attacks, including at least three by Artaxerxes III. In 343 BC Artaxerxes defeated the last indigenous pharaoh, Nektanebo II, and by 341 BC he had conquered all Egypt. Nevertheless, Persian control was fragile, and after Alexander the Great had defeated Darius III’s forces at Issos in 333 BC, he had no difficulty in taking over Egypt.

Fig. 1.1.1 Ptolemy I, Greekstyle basalt head (British Museum EA 1641).

Bibliography: Kienitz 1953; Lloyd 2000; Myśliwiec 2000.

1.1.c The Ptolemaic period

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, his generals at first claimed merely to be satraps, nominally under the authority of his heirs, but in 306 BC one of them, Antigonus, called himself ‘king’, and Ptolemy at once followed suit. The royal line thus established in Egypt lasted for nearly three centuries and was the longest-lived successor kingdom to Alexander’s empire.

The first century of Ptolemaic rule saw expansion abroad and stability and growth at home. Following the battle of Ipsos in 301 BC, the Ptolemies controlled Coele Syria (‘Hollow Syria’), roughly modern Palestine. Ptolemy I added Cyrene, Cyprus and a number of Aegean islands. Ptolemy II added some coastal cities and territories in Asia Minor and fought the neighbouring Seleucid Empire to maintain control over Coele Syria. Ptolemy III invaded Syria proper during one of the Seleucid kingdom’s times of troubles (246–241 BC) and even occupied Seleucia in Pieria, the port city of the Seleucid capital, Antioch. For a brief moment, the Ptolemaic Empire reached its greatest territorial extent. The Seleucid king Antiochus III attempted to regain control of the Ptolemaic possessions in Syria but was surprisingly defeated by Ptolemy IV in 217 BC at Raphia, famous as the first battle in which the Ptolemies made extensive use of native Egyptian troops. This innovation born of desperation was thought by the Greek historian Polybius to mark the beginning of the end of Egypt’s internal social cohesion.

In Egypt the first Ptolemies encouraged the immigration of Greeks, attracting military settlers (cleruchs) from all over the eastern Mediterranean through grants of land. In place of pharaonic Memphis, Ptolemy I made Alexandria his capital city, and established in Upper Egypt a second chief city named Ptolemais Hermeiou. Greek soon became the official language of government. The Ptolemies retained the traditional division of Egypt into forty or so administrative districts called ‘nomes’. Irrigation was extended and new villages founded in the Fayyum and the eastern Delta (Chapters 2, 4 and 5). Alexandria (Chapter 2) became the largest city of the eastern Mediterranean, a commercial entrepôt whose colossal lighthouse, the Pharos, was one of the wonders of the ancient world. Alexandria also became the leading Mediterranean city of arts and sciences under royal patronage of its Museum, Library and zoological gardens.

While the Ptolemies fostered Greek cultural and scientific endeavours, to legitimate their rule to Egyptians they also promoted native cults and their priesthoods by sponsoring and supporting the repair and restoration of existing temples and the construction of new ones, including some of the finest surviving examples. The temples remained wealthy landholders and enjoyed other privileges. As part of their religious policy, the Ptolemies encouraged worship of themselves and their queens as divinities and also fostered worship of the hybrid Graeco-Egyptian god Sarapis, whose cult became popular well beyond Egypt itself, especially in the Roman period (1.4).

In the historical tradition, the second century of Ptolemaic rule is a tale of contraction, disarray and decline. In 204 BC Ptolemy IV was assassinated in a palace coup, which was followed months later by the accession of his son Ptolemy V, barely six years old. Shortly before, the upper part of Egypt, the Thebaid, had revolted, and remained independent under a native dynasty until its recovery in 186 BC. Another long-term revolt, in the Delta, was finally crushed in 185 BC. On the foreign front, in 200 BC, the young Ptolemy’s regents lost Coele Syria to Antiochus III at the battle of Panion. The loss of all the other Ptolemaic foreign possessions followed. Soon Rome began intervening in Egyptian politics. In 168 BC Egypt became, loosely, a Roman protectorate, when Roman diplomatic intervention forced the Seleucid king Antiochus IV, who had invaded in 170 BC and begun to rule Egypt, to withdraw. In 163 BC the Romans restored the ousted Ptolemy VI and his sister-wife Cleopatra II and assigned Cyrenaica to Ptolemy’s opponent and younger brother, Ptolemy VIII. The latter eventually, in 145 BC, succeeded to his brother’s throne in a reign that our sources describe as a disaster in every way. A late attempt to restore harmony to the land is seen in the long series of royal amnesty decrees of the year 118 BC. A major force in these years, from her marriage to her uncle, Ptolemy VIII, in 140/39 BC down to her violent end in 101 BC, was Cleopatra III, daughter of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II.

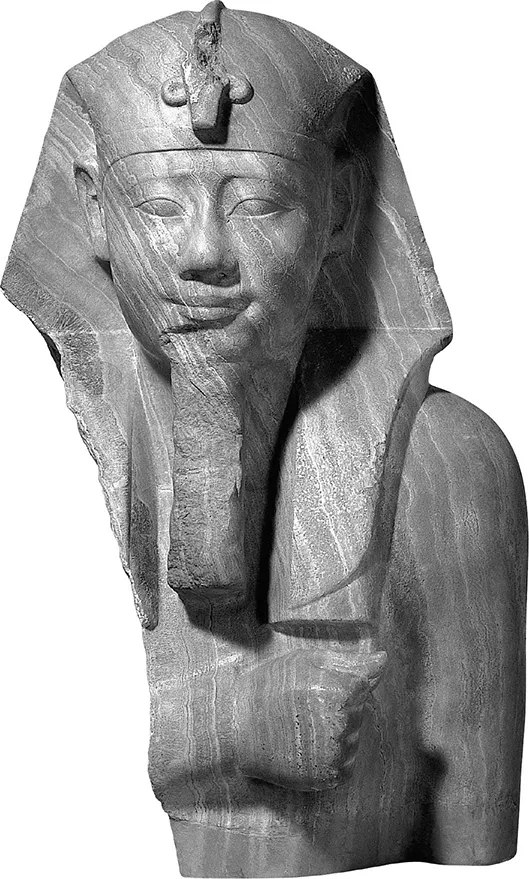

Fig. 1.1.2 Ptolemy II, Egyptianstyle calcite bust (British Museum EA 941).

In the following century, the by now familiar troubles, including civil wars and dynastic assassinations, continued to plague Egypt. There was a second major revolt in the Thebaid in the early 80s. Finally, Egypt became one of the settings for the civil wars that were tearing the Roman Republic to pieces. In 58 BC Rome annexed the Ptolemaic kingdom of Cyprus. After years of exile, Ptolemy XII died in 51 BC, leaving Egypt to his children, Cleopatra VII (col. pl. 1.1.3) and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII. In 49 BC they began waging war against one another. In 48 BC, after his defeat by Julius Caesar at the battle of Pharsalus, Pompey fled to Egypt and was assassinated on the orders of Ptolemy XIII. Caesar entered Alexandria, where he was besieged by Ptolemy, but gained victory – in which Ptolemy XIII died – by allying himself with Cleopatra. Caesar cohabited with Cleopatra and had a son by her, Ptolemy Caesar, known as Caesarion (Little Caesar). Cleopatra followed Caesar to Rome, where she lived until his assassination in 44 BC. Later, at Ephesos, Cleopatra met Caesar’s henchman, Mark Antony, who from 41 BC, when not on military campaign, lived with her in Alexandria. Cleopatra supported Antony in the civil war against Octavian, the greatnephew of Caesar and his adopted son and heir. After the defeat of their fleet at the battle of Actium in 31 BC, they fled to Egypt and committed suicide. Cleopatra’s daughter by Antony was spared by Octavian and was married to Juba, the Roman client king of Numidia.

Bibliography: Chauveau 2000, 2002; Hölbl 2001a, 2001b; Lewis 1986; Turner 1984; Walker and Higgs 2001.

1.1.d The Roman period

Octavian, later known as Augustus, dated his rule of Egypt from 1 August 30 BC, the day he entered Alexandria. As he himself tersely put it in his Res Gestae: ‘I added Egypt to the empire of the Roman people’. Egypt became an imperial province: Augustus, like the Ptolemies, was portrayed in art with the trappings of pharaoh, but Egypt was now directly governed by a Roman ‘prefect’ resident in Alexandria, a distinguished man of the equestrian class appointed by and directly responsible to the emperor. Roman senators, as potential rivals to the emperor, were barred from the wealthy province. Garrisoned by three legions (later reduced to two), Egypt became an important source of imperial revenue, especially of wheat shipped to feed the population of the city of Rome.

The years of Roman rule in Egypt were relatively peaceful and uneventful, not so much a history of ‘events’ as of ‘structures’. Nevertheless, the first prefect, the poet-soldier C. Cornelius Gallus earned the emperor’s displeasure for his military campaign beyond the First Cataract of the Nile into the region known as Nubia, and, more offensively, for vaunting his successes by inscriptions and statues throughout Egypt. Gallus was recalled to Rome, and only escaped judicial condemnation by the Senate through suicide. Military operations on the southern frontier against the kingdom of Meroe occupied Petronius, the second prefect, and resulted in the Roman occupation of Primis (Qasr Ibrim). By a treaty with Meroe, Egypt’s southern boundary was set at Hiera Sykaminos, well south of the First Cataract.

Fig. 1.1.4 Silver denarius of Octavian (Caesar), 28 BC: ‘Egypt captured’ (British Museum C650).

In AD 38, under Gaius, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Alexandria. Subsequently, following another(?) outbreak of violence in AD 41, the emperor Claudius, in his well-known ‘Letter to the Alexandrians’, attempted to end the conflict between the Jewish and Greek inhabitants. Claudius’ successor Nero never acted on his plans to visit Egypt but in AD 61 sponsored an exploration of the ‘Ethiopian’ lands south of Egypt. In the civil war after Nero’s suicide in AD 68, the prefect Tiberius Julius Alexander, scion of an eminent Alexandrian-Jewish family, sided with the victorious Vespasian, who was proclaimed in Alexandria on 1 July 69. Vespasian spent the winter in Alexandria before progressing to Rome, and so did his son Titus after the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Main contributors

- 1 General introduction

- 2 Alexandria, the Delta and northern Sinai

- 3 The Memphite region

- 4 Christian monasticism and pilgrimage in northern Egypt

- 5 The Fayyum

- 6 Middle Egypt

- 7 The Theban region

- 8 Upper Egypt

- 9 The western oases

- 10 The Eastern Desert

- Chronological outline

- Bibliography

- Illustration acknowledgements

- Colour plates