- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

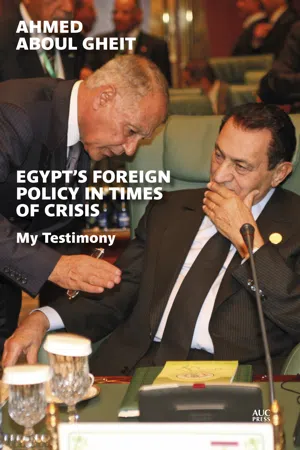

An Egyptian foreign minister's fascinating account of his time in office during the final years of the Mubarak era

Ahmed Aboul Gheit served as Egypt's minister of foreign affairs under President Hosni Mubarak from 2004 until 2011. In this compelling memoir, he takes us inside the momentous years of his time in office, revealing the complexities and challenges of foreign-policy decision-making and the intricacies of interpersonal relations at the highest levels of international diplomacy.

Readable, discerning, often candid, Egypt's Foreign Policy in Times of Crisis details Aboul Gheit's working relationship with the Egyptian president and his encounters with both his own colleagues and politicians on the world stage, providing rich behind-the-scenes insight into the machinery of government and the interplay of power and personality within. He paints a vivid picture of Egyptian–U.S. relations during the challenging years that followed September 11 and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, as we navigate the bumpy terrain of negotiations, discussions, and private meetings with the likes of Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, Dick Cheney, and Hillary Clinton. Successive attempts by Egypt to revive Palestinian–Israeli negotiations, U.S. assistance to Egypt, and the issue of NGO funding get full play in his account, as do other matters of paramount concern, not least Egypt's strenuous attempts to reach an agreement with fellow riparian states over the sharing of the Nile waters; Sudan, Libya, and Cairo's engagement with the wider African continent; the often tense negotiations surrounding UN Security Council reform; and relations with Iran and the Gulf states.

More than a memoir, this book by a senior statesman and veteran of Egypt's foreign affairs is a tour de force of Middle Eastern politics and international relations in the first decade of the twenty-first century and an account of the powers and practice of one of Egypt's most stable and durable institutions of state.

Ahmed Aboul Gheit served as Egypt's minister of foreign affairs under President Hosni Mubarak from 2004 until 2011. In this compelling memoir, he takes us inside the momentous years of his time in office, revealing the complexities and challenges of foreign-policy decision-making and the intricacies of interpersonal relations at the highest levels of international diplomacy.

Readable, discerning, often candid, Egypt's Foreign Policy in Times of Crisis details Aboul Gheit's working relationship with the Egyptian president and his encounters with both his own colleagues and politicians on the world stage, providing rich behind-the-scenes insight into the machinery of government and the interplay of power and personality within. He paints a vivid picture of Egyptian–U.S. relations during the challenging years that followed September 11 and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, as we navigate the bumpy terrain of negotiations, discussions, and private meetings with the likes of Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, Dick Cheney, and Hillary Clinton. Successive attempts by Egypt to revive Palestinian–Israeli negotiations, U.S. assistance to Egypt, and the issue of NGO funding get full play in his account, as do other matters of paramount concern, not least Egypt's strenuous attempts to reach an agreement with fellow riparian states over the sharing of the Nile waters; Sudan, Libya, and Cairo's engagement with the wider African continent; the often tense negotiations surrounding UN Security Council reform; and relations with Iran and the Gulf states.

More than a memoir, this book by a senior statesman and veteran of Egypt's foreign affairs is a tour de force of Middle Eastern politics and international relations in the first decade of the twenty-first century and an account of the powers and practice of one of Egypt's most stable and durable institutions of state.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Egypt's Foreign Policy in Times of Crisis by Ahmed Aboul Gheit in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE ASSIGNMENT

I entered my office in the headquarters of the Egyptian permanent mission to the United Nations at 344 East 44th Street in New York at 3:45 p.m. on Friday, July 9, 2004. In less than five minutes, the phone started ringing and my Nigerian secretary, Stella, said, “This call is for you from Cairo.” She told me the name of the caller—someone who was part of the inner circle of the president’s staff. He said that he was making the call from the Heliopolis Sheraton hotel, not from his home or office, because he did not want anyone to know about it at present. I had been selected as the minister of foreign affairs in a new cabinet in Egypt that would be announced within days. He added that I should not talk about it to anyone and that I would get a phone call from the prime minister-designate about this position. I thanked him for the news and for his enthusiasm about it.

The previous night, at dawn on Thursday, July 8, a well-connected former ambassador in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who was on good terms with various members of the Egyptian elite had called my New York apartment to relay the same news. He said that he was certain that the decision had already been made about my appointment as minister of foreign affairs and successor to my lifelong friend Ahmed Maher. Maher had already succeeded our friend Amr Moussa on May 15, 2001, when the latter was elected as secretary general of the League of Arab States, replacing Dr. Esmat Abdel Meguid, who had held that position for ten years during which Amr Moussa had been the foreign affairs minister.

I kept thinking about the calls and began to think that the news might be true. I had been told that since Amr Moussa left the ministry in 2001, President Mubarak had been thinking about some names and that mine was at the top of his list. Even more, just after the announcement that Egypt intended to nominate Moussa as secretary general of the Arab League, the Saudi newspaper Asharq al-Awsat reported from London in the middle of April 2001 that “Aboul Gheit is the candidate most likely to get the position.” However, I thought that the president might choose someone else closer to him since he did not know me really well. Until then, I had met the president personally only twice throughout my service as a diplomat. The first time was during his visit to Italy in November 1994 when I was the Egyptian ambassador there. The Italian authorities had decided then that it was dangerous for him to stay in a hotel in Rome because they had intercepted suspicious phone calls during that period when Egypt was confronting serious terrorist threats. Thus, the president spent his night at the Villa Savoya—the headquarters of the Egyptian Embassy—where Italian monarchs had lived during and before the Second World War, and where the Italian Carabinieri had arrested Mussolini during his visit to the king of Italy, to discuss the progress of the war and the possibility of the withdrawal of Italy to save itself a crushing defeat. The president’s visit was a success, and later, one of the inner circle of the president’s officials told me in a phone call that the president liked the warm hospitality and expressed his satisfaction, commenting on my wife and myself as “a really exceptional and excellent couple.” The second time I met the president was before I left to New York as the permanent representative of Egypt to the United Nations in 1999; it was in the Heliopolis Presidential Palace and lasted for twenty minutes in the presence of Amr Moussa, the minister of foreign affairs at the time.

Since 1989, I had heard from high-profile friends in the government that the president kept asking about personnel in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who could be promoted. They often mentioned my name and he would answer that he was sure about my good reputation and wide experience, in addition to the fact that my father was one of his acquaintances and they had served together in the air force. However, he would sometimes add, “Isn’t he a bit young for the position?” I found President Mubarak’s age-sensitivity when it came to decisions about promotions and assigning positions strange; seniority clearly meant a great deal to him.

When President Mubarak asked Dr. Esmat Abdel Meguid about someone to replace Ambassador Amr Moussa, the permanent Egyptian representative, upon the latter’s return from New York in April 1991, Abdel Meguid suggested my name. Again, the president’s response was that he found Aboul Gheit “young for the position,” although I was forty-nine years old at the time! I found this attitude extremely provocative, and I was even more vexed and exasperated after Amr Moussa was assigned to succeed Esmat Abdel Meguid as minister of foreign affairs and Moussa’s recommendation to the president to extend the service of a group of Egyptian ambassadors for years beyond their normal retirement age. I firmly believed that extending their service, even though I never doubted their efficiency or denied their competence, denied opportunities for many high-caliber people that my friend and colleague Dr. Mustafa al-Fiqi called “the generation of the mezzanine floor” (that is, the lost generation). I had already decided never to follow that path myself, and I assured the president, when I became foreign affairs minister, that I had no intention or desire to approach him in the future with a recommendation to extend the service of any ambassador, whether inside Egypt or abroad, beyond the retirement age. In fact, there had been attempts in the years following my appointment that I firmly resisted. The president’s wife had tried to extend the service of some of the women ambassadors beyond the retirement age and I refused; the president was supportive, despite the pressures I believe he had felt from his family.

The first six months of 2004 were rife with many of the usual rumors about the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, among which was that Ahmed Maher would not continue for long at the helm of Egyptian diplomacy, especially after his visit to Jerusalem, which was not a success. Some Palestinians allied to an extremist organization gathered and protested against his visit to the al-Aqsa Mosque in a repugnant manner that displayed their ingratitude for Egypt’s efforts and sacrifices on behalf of the Palestinian cause and its support of the Palestinian people to claim their rights in Palestine generally, and particularly in Jerusalem, for decades. These rumors spread widely after Ahmed Maher suffered from a severe illness in 2004 that caused him to be rushed to a hospital in Cairo; he was thus unable to accompany the president on a visit to America.

Maher had actually suffered two major health crises. The first was in 1983 when he was the Egyptian ambassador to Belgium and the European Community in Brussels; the second happened in 1993 when he was ambassador to Washington. In both cases, he underwent major heart surgeries that required him to remain under close medical supervision. However, he had always found ways to dodge doctors’ instructions and escape the supervision of his wife in her continuous attempts to make him follow those instructions by supervising his meals and activity.

During the years 2002–2003, when I was the permanent representative in New York, Ahmed Maher, the-then minister of foreign affairs, visited many times and seized the opportunity to undergo some medical checkups in the main hospital of Cornell University. Most of his tests were concerning, and I often asked the Egyptian physician not to talk about them to anyone to keep his image intact. I did not know then whether Maher himself had told anyone in Cairo about the results of his tests or not, but I was sure that some official and personal reports were sent to Cairo, whether to the president’s office or to some other Egyptian government agencies. I was also aware that when President Mubarak chose Ahmed Maher to succeed Amr Moussa, he was worried that his responsibilities would indirectly affect his already vulnerable health. Nevertheless, the president preferred to choose someone known for his efficiency, and whom he had known well for many years during his work in Washington from 1992 to 1999 and in Moscow from 1988 to 1992.

Returning to the subject of my nomination to the position: I have always believed that the Egyptian permanent representative to the United Nations, whether personally known to the president or with no direct relation to him—as in my case—was invariably one of the candidates for the position of foreign affairs minister in case unexpected changes happened at the head of this ministry. There had been many instances of this kind, starting with Dr. Mahmoud Fawzi in 1953 and followed by Mahmoud Riyad in 1964, Mohamed Hassan al-Zayyat in 1969, and Dr. Esmat Abdel Meguid in 1984, who was succeeded by Amr Moussa in 1991. Therefore, I believed that there was really a strong possibility of my appointment to that position.

President Mubarak came back to Cairo a few days before July 10 after undergoing major spine surgery and staying in Germany for some weeks. It was then rumored that a major cabinet reshuffle was expected in Cairo shortly. On July 8, an editorial by Ibrahim Nafie was published in al-Ahram in which he severely criticized the policies of the Egyptian government and the performance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This led me to conclude that there was a serious possibility that the minister of foreign affairs would be replaced.

I monitored the matter closely, not only because I was a potential candidate for the position, but also because I did not wish to serve under a minister who was either younger than myself or whom I outranked in the diplomatic corps. Therefore, I had to be prepared to go back to Cairo and enjoy a relaxed life after thirty-nine years of hard work during which I devotedly served my country’s diplomacy. I was then sixty-two years old and had already received three presidential decrees to extend my service beyond the retirement age, each decree granting one additional year.

What I felt that day, July 9, was a sense of anticipation. I decided to call my wife, Laila, via the direct connection between my office and the residence of the Egyptian ambassador on Park Avenue. I told her about the phone call I had received from one of the members of the president’s office, and of course she already knew about the earlier call from the retired Egyptian ambassador. She cried and said that she did not want me to take this position because of its overwhelming responsibilities that would take me away from her for however long I served in that post. She also said that the years of our lives had gone by far too quickly and that we were not getting the chance to rest, relax, and enjoy each other’s company. I replied that if what I had been told about my imminent appointment was true, I could not refuse the president’s trust, since neither my personality, work ethics, nor training as an Egyptian diplomat allowed me to do so. I assured her that I was absolutely convinced that men must accept responsibilities and never run away from them, especially if they are sufficiently qualified. I firmly believe that this philosophy governs the conduct of all diplomats and other high-profile officials when they receive a request from their president to perform a certain task, whether big or small. I was following Al Jazeera television while talking to my wife and suddenly I saw my photograph and name on the screen, together with the news that I was to be the next Egyptian minister of foreign affairs.

Phone calls poured into the headquarters of the delegation from colleagues in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, our embassies abroad, and my family in Cairo. I decided to leave the building and go out with one of the young members of the delegation, the well-qualified Mohamed al-Farnawany. We leisurely strolled through New York’s streets for hours, looking at shop windows and entering bookstores. I arrived home in the evening to find that my wife had disconnected most of the phones in the apartment, especially since it was just after dawn in Cairo and no one was expected to call. She said she had received dozens of calls, and that was just a sample of how our future life would look.

It might be relevant here to narrate a funny story that happened to one of the diplomats in our delegation, Counselor Mahmoud Sami. I accompanied him one Friday from the office to my apartment to discuss some matters and have a light lunch, then go back. It was a hot and humid day and we walked about three kilometers; when we arrived, he was soaking with sweat and in bad shape. We finished talking and had lunch, then I showered quickly and we were all set to go back. When I suggested that we go on foot, he firmly refused and said that he never refused any of my requests but he could not stand walking in the heat and humidity. I started teasing and threatening him, and he said that he knew that I would most probably be the minister of foreign affairs within days or even hours, but he would not walk in the heat no matter what happened. So he went back in my car and I walked to the office. As soon as he heard the news on Al Jazeera, he came to tease me, suggesting that, now that I had become foreign minister, he was prepared to walk back and forth from my home to the mission many times and make it a daily routine, and we laughed.

I tried to sleep that night but slept only fitfully. On July 10, 2004, I received a phone call at 6:00 a.m. from the Cabinet switchboard in Cairo and was told that Dr. Ahmed Nazif wanted to talk to me; then General Abu Talib, Dr. Nazif’s chief of cabinet at the Ministry of Communication, also said that Dr. Nazif wanted to speak to me. I waited on the line for a couple of minutes and did not hear anyone so I hung up. The Cabinet headquarters called again and Dr. Nazif was on the line; he courteously said that he still remembered his last successful visit to New York the previous year when he came on an official mission related to the Ministry of Communication. He said that he was calling to deliver the “president’s appeal” for me to accept the position of the minister of foreign affairs in the next cabinet. I was surprised by his cordial style in handling the subject. I thanked him and asked him to thank the president for his trust. He said that I was expected to arrive in Cairo before Sunday noon for the swearing-in, which was expected to be on Monday, July 12. I jokingly commented that the position had already started to weigh heavily on me and that I would spare no effort to leave New York on Saturday, July 10.

I requested a farewell meeting with all the members of the delegation and wrote a short note to the secretary general of the United Nations, apologizing for my unexpected departure. I also prepared a memorandum to be sent to the ambassadors of all countries, notifying them of the circumstances of my departure, as was the customary method of diplomatic communication in such cases. While my wife was packing my summer clothes, I got ready to travel via the EgyptAir flight leaving for Cairo at 10:00 p.m.

We agreed that my wife would stay in New York for a few weeks to tend to our personal belongings before coming back to Cairo. This created a small problem: my son’s fiancée was expected to arrive in New York with her sister on the same day I was to leave. Thus we met at the airport; she arrived and I left. To give my wife her due, I must admit that I have always burdened her with a lot of responsibilities, or to be exact, all familial responsibilities. For the thirty-six years of our marriage up to 2004, she raised and nurtured our children, Kamal and Ali, and supervised their education. My sole duty has been to work, and I am sure that had it not been for her constant support, I would not have achieved the success I did in my professional career.

The EgyptAir flight took off on time, and though I was very exhausted, I could not get a wink of sleep. I recalled many of the stages in my professional career, and how things developed from June 1, 1965, the day I joined the Egyptian Foreign Affairs Ministry, to the day I left New York to go home to be the foreign affairs minister. I also thought about the coming mission and the great responsibilities it entailed. Egypt is a big country with major status, significant responsibilities, and an important role in the Middle East, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Red Sea. Furthermore, Egypt has a visible presence in all global policy circles, especially at the United Nations and its various specialized agencies, and is actively engaged in discussions on a wide range of issues. Egypt has shouldered many responsibilities and still does, especially when it comes to dealing with the Arab–Israeli conflict, both during the armed confrontation period and in the quest for a peaceful settlement, as we have witnessed since Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem in November 1977.

Based on my reading of Egypt’s history and its role in international developments over the last two hundred years, I was deeply convinced that Egypt has great international importance, not only because of its geographical location, but also because of the vitality and vigor of its people under any visionary and effective leadership. This was the source of Egypt’s ability to influence its vital sphere and the wider interests of many superpowers whenever it got the chance. As an Islamic country, Egypt’s magnitude attracts the attention of millions of Muslims. As an Arab country, Egypt has been at the forefront of defending an Islamic and Arab region, which was for centuries subjected to violent attacks from the Christian west, including the Crusades, the appearance of the Portuguese in the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf in the sixteenth century, the fleets of Venice and Genoa in the Mediterranean at the end of the Mamluk era, and until the beginning of the Ottoman dominance. Egyptian leaders and rulers have always been required to lead its foreign policy and protect its security and interests in the midst of incessant competition between the great powers, which always projected their power and exercised their influence in the region.

When Mamluk Egypt came under the control of the Ottoman Empire for several centuries, efforts were made, from time to time, to escape this dependency within the limits of the circumstances prevailing at that time. For centuries, the rulers of Egypt made more than one attempt to achieve a degree of independence, and then to influence developments in its immediate surroundings, especially in the Mediterranean. Ali Bey al-Kabir, for example, attempted to escape the complete dominance of the Ottoman Empire and allied himself with Russia in order to exert pressure on the Ottomans. Another example is Muhammad Ali Pasha’s conflict with the Ottoman Empire and his rapprochement with France. Then came Gamal Abd al-Nasser and the revolution of 1952, thwarting the plans of the western powers—the United States and the Anglo-Saxon allies—and getting closer to the Soviet Union.

All these ambitious attempts on the part of the rulers of Egypt to expand its external influence and regional clout failed. Despite the initial success of leaders such as Ali Bey al-Kabir, Muhammad Ali Pasha, and finally Gamal Abd al-Nasser in expanding Egyptian geopolitical influence into areas such as the Arabian Peninsula, the Red Sea and its southern approaches from the Horn of Africa and the Eritrean lands, and as far as the headwaters of the Nile, these leaders ultimately failed to ensure sustained Egyptian influence over these areas.

Tracing Egyptian diplomacy over a period of two hundred years from 1775 to 1975, I came to the conclusion that in its attempt to achieve its goals, Egypt leveraged the global balance of power and the interests of the great powers to serve its own interests. Ali Bey al-Kabir took advantage of Tsarist Russia’s ambitions in the Mediterranean and its desire to gain access to warm waters and control the Black Sea straits to help Egypt escape Ottoman domination. However, this attempt, which entailed a great deal of Egyptian effort, failed for several reasons, the most important of which was the interference of the greatest navy in the world at that time—that of the British Empire. One more possible reason for the failure of Egypt’s efforts was its early extension beyond its own borders, which revealed its intentions prematurely before it could build up its internal front.

Muhammad Ali Pasha, on the other hand, to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Ded

- Forword

- Intro

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Conclusion